It was a late night in February when some 50 government soldiers charged into Kham Yi’s village in northeastern Burma’s Shan state. Brandishing assault rifles, the troops demanded food and shelter. Distraught villagers watched as the soldiers plundered their homes and slaughtered their livestock.

The following morning, the village was split into groups according to gender. Some men were taken to a local monastery where their hands were tied behind their backs and they were forced to lie face down in the dirt. The soldiers kicked them and whipped them with sticks, demanding to know the whereabouts of armed rebels representing their ethnic group, the persecuted Ta’ang minority. Then they grabbed a small boy and forced him to identify members of the guerrillas, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA).

The child pointed at Kham Yi, whose son was forcibly recruited by the rebels some time earlier. He was quickly bundled away for interrogation.

“They beat me on my arms, my chest and my back,” recalls the 50-year-old laborer, shifting nervously. “Another soldier said, ‘If you don’t tell me [where the rebels are], I will douse you in petrol and set you on fire.’”

Read More: 5 Challenges Facing Burma’s New Civilian Government

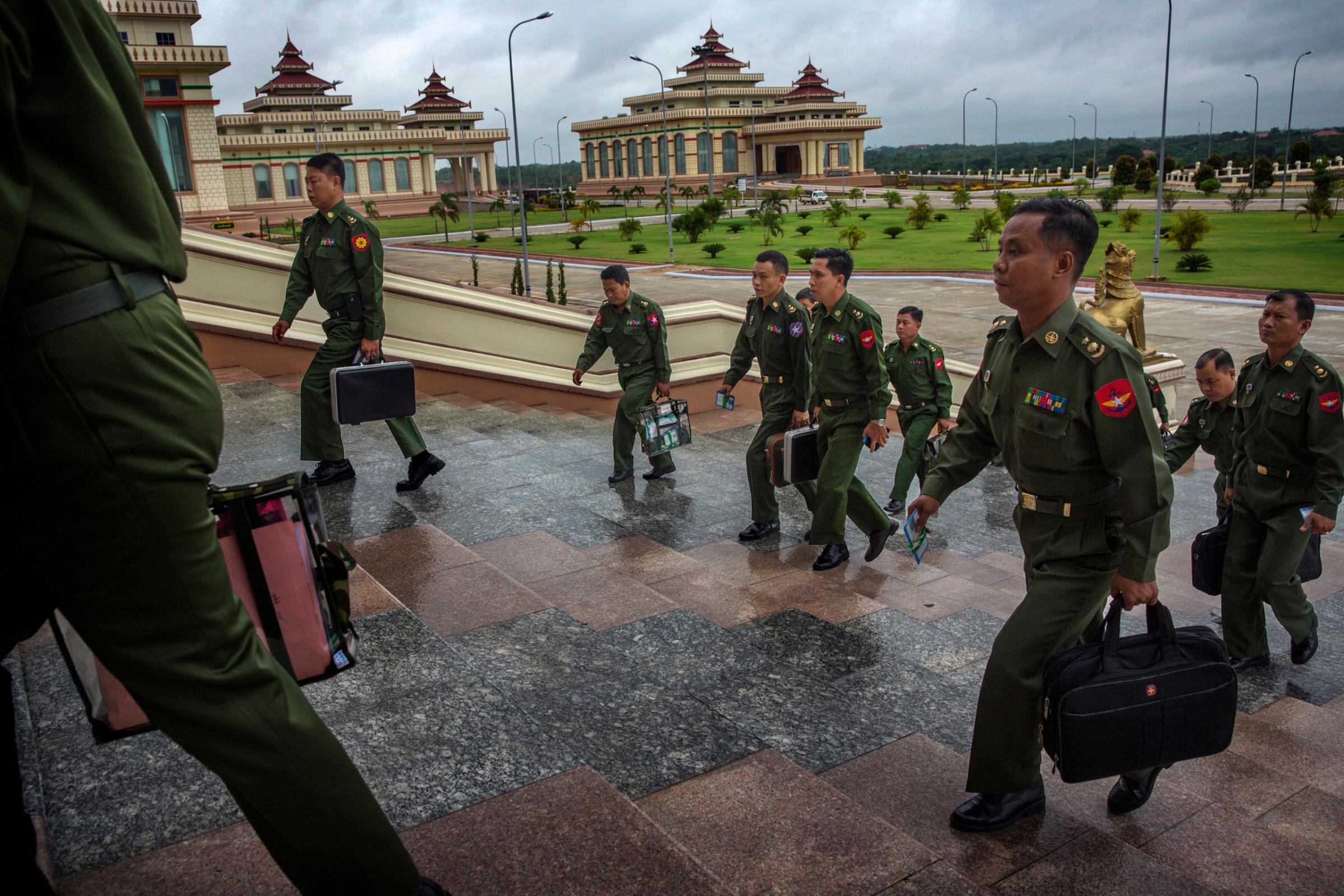

Ethnic armed rebels have been fighting for rights and self-determination in Burma, officially known as Myanmar, for decades. In the wake of a military coup in 1962, many of the nation’s myriad ethnic groups formed rebel armies in a bid to realize their own dominions (the country’s border areas are divided into seven ethnic states, and the government estimates there are 135 distinct ethnic groups). Today, with a civilian government installed under the de facto leadership of democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi, ethnic violence is escalating in northern Burma, with torture and violence against civilians increasingly common. Suu Kyi, who trounced her opponents in Burma’s first open election in decades in November, has vowed to prioritize the peace process and end the country’s long-festering civil wars. But the Burmese military remains outside civilian control and continues to wield significant political power.

Thousands of people have been displaced in recent weeks as the Burmese army stepped up its offensive against rebel groups that were excluded from a nationwide cease-fire agreement last year. Locally known as the Tatmadaw, the military that ran the country for half a century until 2011 has a notorious reputation for abusing civilians in the country’s volatile ethnic regions.

In February, a disturbing video surfaced on social media seeming to show government soldiers and an affiliated militia flogging Ta’ang civilians in a village near Namkham in southern Shan state. The scene was reminiscent of the one described by residents interviewed by TIME. The Ta’ang Women’s Organization (TWO) and Ta’ang Students and Youth Organization have recorded dozens of cases of torture involving the military in the past few months alone, which typically involve soldiers targeting ethnic minorities believed to have ties to armed rebels, fueling suspicion that it is a calculated strategy.

“My body was so battered I no longer cared if I lived or died”

“In some villages more than 10 people [have been tortured],” says Moe Kham, general secretary of the TWO. “This is [the military’s] policy. Sometimes they burn the village or destroy their property … They think they are putting pressure on the ethnic armed groups. This is one way they are oppressing the people.”

Read More: Inside the Kachin War Against Burma

A spokesperson for the government declined to comment, and the military could not be reached for a response despite repeated attempts by TIME.

Several other Ta’ang villagers reported similar incidents of abuse. Aik Lock says he was bound, blindfolded and gagged after the Tatmadaw discovered a notebook belonging to the TNLA in his home. He assumes rebel soldiers left it behind when they last camped in his village. The army beat him throughout the night.

“My body was so battered I no longer cared if I lived or died,” he says. His account is backed up by photographs showing his injuries.

Kham Yi and Aik Lock say they were brutalized so severely they were unable to walk. They were confined in a military detention center in Kutkai until a local monk, a member of the Buddhist nationalist group Ma Ba Tha, negotiated their release at the start of March.

Other villages in the region have been torched or even shelled by government soldiers, according to witnesses interviewed by TIME. At one, over 14 civilians were abducted for forced labor.

“Abuses are part and parcel of Tatmadaw military culture, fostered by six decades of counterinsurgency operations all over the country,” says Anthony Davis, a regional security analyst with IHS-Jane’s.

Rebels have also been accused of crimes, including extrajudicial killings and conscription of both Ta’ang and Shan civilians. The TNLA has a policy that requires every ethnic Ta’ang family to contribute one fighter.

“We do have a recruitment drive but we recruit only Ta’ang people, no other ethnicities,” says TNLA spokesperson Mong Aik Kyaw, adding that only one able-bodied man from families with at least two sons is conscripted. “If one of them has some kind of disability, then we won’t demand the other to join.”

An inclusive and durable cease-fire

Ethnic conflict has engulfed Burma since the country gained independence from British rule in 1948, aggravated by decades of junta rule and militarization. In October 2015, a reformist government led by President Thein Sein inked a controversial cease-fire deal — supported by millions of dollars in international funding — with only eight out of over a dozen armed groups. The military excluded key parties from the process, including the TNLA.

Read More: Rape Is a Weapon in Burma’s Kachin State, but the Women of Kachin Are Fighting Back

Since then, the army has escalated its offensive against nonsignatory rebels, allegedly in cooperation with a competing group, the Shan State Army-South (SSA-S), which was party to the cease-fire and now appears to have moved over a thousand of its troops across large swaths of government-held territory. Analysts say it forms part of the Burmese army’s long-term strategy to foster ethnic discord.

“This is the continuation of a very long pattern by the Myanmar army of managing conflict but never solving it,” says Tom Kramer from the Transnational Institute, a policy group of scholars that focuses on democracy, social justice and ecological sustainability. Kramer adds that “divide and rule” tactics have been used by the military for decades.

Mong Aik Kyaw says the rival SSA-S began moving troops almost immediately after making peace with the army. “Without some kind of understanding with the government, it would be impossible for them to mobilize across such a distance,” he says.

The Burmese army and Shan rebels have denied collaborating with each other, with the latter insisting that it is reclaiming territory from the TNLA using soldiers based in the area. Min Zaw Oo, director of cease-fire negotiation and implementation at the state-backed Myanmar Peace Center, tells TIME that the Tatmadaw has repeatedly urged the Shan group to pull back its troops.

Building an inclusive and durable cease-fire will present a major challenge for Suu Kyi when her government takes office on April 1. The military operates autonomously of Burma’s elected establishment, controlling 25% of seats in parliament and holding an effective veto over constitutional reform. All defense-related decisions must pass through the National Defense and Security Council (NDSC), in which the army holds a majority. The Tatmadaw also runs the crucial Border Affairs Ministry that manages Burma’s war-torn ethnic regions.

“The NLD government will have a very hard time to control the conflict because they don’t control the [relevant] ministries, they don’t have a majority in the NDSC, and they aren’t in charge of the Myanmar army,” explains Kramer. “Even if the President says we should stop this conflict and there should be no more offensive operations, it won’t actually have any impact.”

Read More: Who Is Htin Kyaw, Burma’s New President?

As a result, any resolution of Burma’s entrenched civil conflicts and related abuses will rest largely on the goodwill of the Burmese army. Suu Kyi will have to tread carefully in the hopes of negotiating a way forward. But early signs point to a growing rift between her and the armed forces, which have repeatedly blocked the Nobel laureate’s attempts to become President of Burma. (Despite winning a landslide victory in November, she is constitutionally barred from the post due to her two sons having foreign citizenship. Her close friend and personal confidant Htin Kyaw is President as her proxy.)

The military recently appointed Myint Swe, an infamous hard-liner and loyalist of former dictator Than Shwe, to the role of First Vice President. This decision has been interpreted as an effort to stymie Suu Kyi’s effort to push for constitutional reform in Burma, seen as necessary to end its ethnic conflicts and secure its democratic credentials. Some observers doubt that the army will seek to make the current cease-fire more inclusive as peace would weaken its political clout.

“[The army] can have no interest in encouraging a comprehensive [national cease-fire agreement] followed by an inclusive political dialogue that will be controlled by a civilian government they do not trust,” adds Davis. “They would in effect be giving up a key card.”

Exploiting the peace process

Describing the violence in northern Burma as “complicated” with abuses on all sides, Min Zaw Oo accuses some ethnic groups of exploiting the peace process by mobilizing troops to fortify their bargaining position. He identifies the Ta’ang rebels’ collusion with another armed ethnic group in February 2015 as a deal breaker for the army.

“From the Tatmadaw’s perspective, the TNLA were taking advantage of the negotiations,” he says. “The [rebels] wanted to get recognition from the government so they needed to show that they could fight.”

Armed ethnic groups and the ruling NLD have repeatedly called for the creation of an inclusive federal union as the political resolution to Burma’s conflicts. But there has been little discussion of political devolution or key aspects of power sharing, such as the sharing of natural-resource revenues and the representation of minorities. Nor is there agreement on how many armed ethnic groups should be recognized and included.

“The [national cease-fire agreement] talks about federalism, but it doesn’t discuss what that means,” says Moe Kham of TWO. “We need to change the constitution. It will take time, but if [the army] really wanted peace it would not be so difficult. The problem is that the military still has power.”

Read More: Thousands of Refugees Are Pouring Into China to Escape Fighting in Burma

A nexus of government-backed militias, which operate under the auspices of the Burmese army, pose another problem for minority communities in conflict zones. Paramilitary groups enjoy official protection, shielded by a clause in Burma’s 2008 constitution, and are known to make lucrative profits from the country’s thriving trade in including heroin, opium and methamphetamines. They have had confrontations with armed ethnic groups, such as the TNLA and their northern neighbors the Kachin Independence Army, who pursue a strong antidrug stance and regularly torch opium crops discovered in their territories.

Burma Counts Down to Elections But Democracy Remains a Distant Dream

“The [militias] are under the control of the Myanmar military so any unilateral decision by the NLD is not going to disband them,” says Kramer. “They are clearly also not part of the peace process and these militias contribute to enormous militarization in ethnic areas.”

Indeed a number of militia leaders have served in parliament for the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). Suu Kyi has even nominated the incumbent USDP representative for Kutkai Township T Khun Myat — a known militia leader and alleged drug trafficker — as her Deputy Lower House Speaker. The decision has raised eyebrows among ethnic minority communities who fear that militias and soldiers will continue to operate with impunity.

Activists say that human-rights protections must be integrated into the peace process, but the prospect seems distant for villagers who live in daily fear of violence. One of those is Ei Mya, a 33-year-old farmer whose village was assaulted by the Burmese army on the same day Htin Kyaw was elected as Burma’s next President in the capital Naypyidaw. She hid in the forest as gunfire and mortar shells rained on her village.

“When we came back we saw that every house had been burned,” she says. “The fire was getting bigger and bigger. I lost everything.”

She says that a child from her village saw government soldiers go house to house with a torch. The entire village was destroyed. She is now living in a remote displacement camp with hundreds of people who are either unable or unwilling to go home.

Like the rest of her village, Ei Mya was not given a chance to vote in last year’s elections and had not heard much about Burma’s tilt toward democracy. Asked if she knew that Suu Kyi was about to take power, she looks shocked and confused. “I heard from somebody that there was an election, but no political party came to our village. I don’t know who won or who lost. No one has talked to us.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com