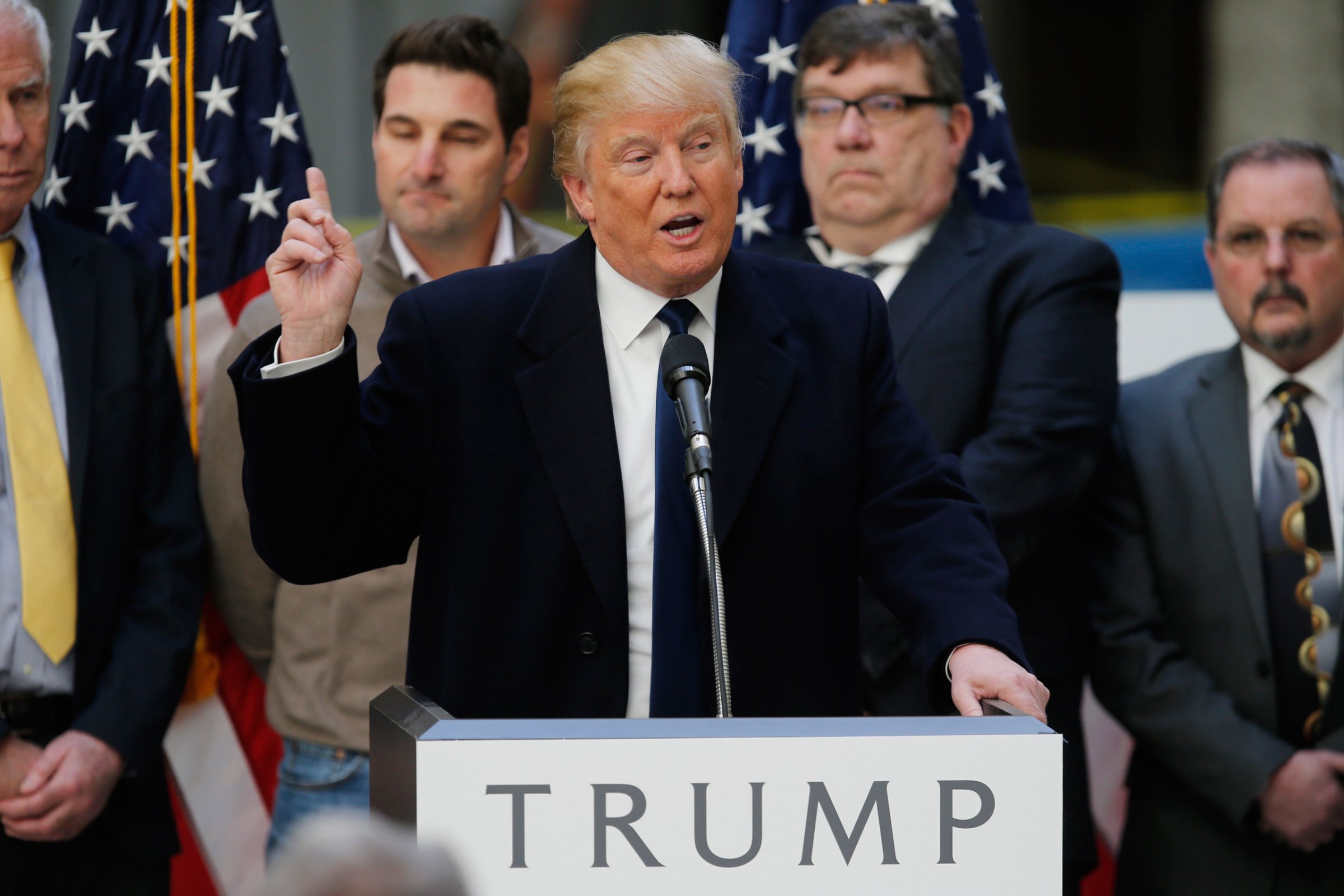

It’s no secret that Donald Trump loves a good lawsuit. Over the years, he’s sued former business partners, a journalist, and at least one little old lady—and on Sunday he promised to bring that litigious spirit to the 2016 presidential race.

Facing an organized effort by rival candidates to game state selection rules and undermine his delegate haul, the Republican front-runner is threatening to sue for votes ahead of a potentially contested convention, a move that could foreshadow a new phase in the GOP’s ugly primary fight. “Just to show you how unfair Republican primary politics can be, I won the State of Louisiana and get less delegates than [Texas Sen. Ted] Cruz—Lawsuit coming,” Trump tweeted on Sunday.

With the GOP race potentially heading to a showdown in Cleveland in which no candidate holds a clear majority of delegates at the convention, every remaining state contest to accumulate committed supporters could face similar scrutiny. With the stakes so high, it seemed such lawsuit threats would abound.

But less than 24 hours after Trump’s tweeted threat, his campaign backed down. Barry Bennett, a Trump senior adviser focused on his delegate operation, said Monday that Trump’s “lawsuit” was not in fact meant for a court of law, but for the Republican National Committee’s committee on contests—which under GOP rules hears complaints over the allocation and selection of delegates.

It’s clear why. Election lawyers and party operatives said challenges to the arcane state-by-state delegate selection rules being used to outfox Trump would face an unwelcome reception in court.

Political parties are non-democratic entities, and while individual states may set laws governing some of the conduct of primaries and caucuses, national party rules generally have supremacy in federal court.

“The parties are given broad leeway to choose their nominees,” said Heather Gerken, a professor at Yale Law School who specializes in election and constitutional law. “The courts are generally averse to jumping into politics generally—they never want to be seen as choosing the winners—and judges are particularly reluctant to interfere with the nominating process. As a general matter, then, they treat the parties like adults and let party leaders sort things out.” Gerken added that the one exception is when the parties are involved in some sort of discrimination.

In the 1974 case Cousins v. Wigoda, for example, the Supreme Court held that “a National Party Convention serves the pervasive national interest, which is paramount to any interest of a State in protecting the integrity of its electoral process.”

A 1981 case, Democratic Party v. Wisconsin ex rel. La Follette, went even further. Political parties “enjoy a constitutionally protected right of political association under the First Amendment,” the justices wrote. Subsequent cases have used a strict scrutiny test when considering party rules.

Trevor Potter, a former Chairman of the Federal Election Commission and the president of the Campaign Legal Center, said he was unfamiliar with the specifics of Trump’s Louisiana complaint, but that the legal precedent was clear. “I certainly agree that Wigoda stands for the proposition that the Courts should generally stay out of political party delegate selection processes,” he said.

A Trump suit could also find itself in trouble on procedural grounds under the legal doctrine of laches—a defense that suggests the plaintiff simply waited too long to file the lawsuit. In Trump’s case, it could be argued that the state party rules had been set for months and the national party rules for more than a year, and he only filed suit after he failed to secure his delegates.

Louisiana might not even be the best test case for Trump’s questionable legal strategy, as there’s little risk of Cruz-supporting delegates infiltrating his supporters: Trump’s Louisiana delegates are drawn from a slate his campaign submitted.

The latest twist started after the Louisiana primary on March 5, which Trump won by 3.6 percentage points. Because delegates from the contest are allocated proportionally under state party rules, Trump and Cruz each secured 18 delegates. Marco Rubio earned five delegates and five more were unbound. A week later, at the state party’s convention on March 12, Cruz supporters, with the help of the Rubio and unbound delegates, were elected to the powerful convention committees that would govern a contested convention.

Bennett maintained that Trump’s delegates were never invited to the meeting when the delegation officers and convention committee representatives were elected. “Our invitations to the secret meeting got lost in the mail,” he said, saying that would be the basis for their challenge.

Trump’s fixation on the process in Louisiana apparently stems from a Wall Street Journal article, which revealed his campaign was unaware that it lost out on the critical convention committee slots. Bennett said that was the first Trump’s campaign or its delegates learned of the meeting. “They don’t get to elect people without our input,” he said.

Louisiana GOP executive director Jason Doré rejected the notion that Trump had been treated unfairly. And at least several Trump delegates—and two state co-chairs—were at the meeting. “He got 40% of the votes, he got 40% of the delegates,” Doré told TIME Monday.

“I have millions of votes more,” Trump said Sunday on ABC’s This Week. “I have many, many delegates more. I’ve won areas. And he’s trying to steal things because that’s the way Ted works, OK. Uh, the system is a broken system. The Republican tabulation system is a broken system. It’s not fair.”

Trump has occasionally used lawsuits as a means to exact retribution, suing a journalist for $5 billion for what Trump considered a low estimation of his net worth. A New Jersey judge tossed out the suit. “I spent a couple of bucks on legal fees, and they spent a whole lot more. I did it to make his life miserable, which I’m happy about,” Trump later boasted to the Washington Post. Earlier this year he also threatened to sue Cruz to make the case that his Canadian birth made him ineligible to serve as president. The suit was never filed.

For all of Trump’s familiarity with the court room, the Louisiana case has him playing on unfavorable ground, as he takes on experienced election lawyers in the party apparatus, not to mention his closest competitor, Cruz, a former Supreme Court clerk who has argued cases before the high court.

“You know what, who cares,” Cruz said Monday during a news conference in Wisconsin. “I’m almost amused when Donald doesn’t know what to do and threatens a lawsuit.”

The nine-member RNC committee on contests is made up entirely of members of the party’s governing body, only one of whose 168 members has endorsed Trump.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com