The shooting of hundreds of people in the Vietnamese village of My Lai in 1968 marked a pivotal turning point in America’s feelings about the the Vietnam War. But while public awareness of the massacre, which spread in the year after the event, stoked anti-war sentiment, the verdict in the trial of one of the soldiers held responsible elicited a more complicated reaction.

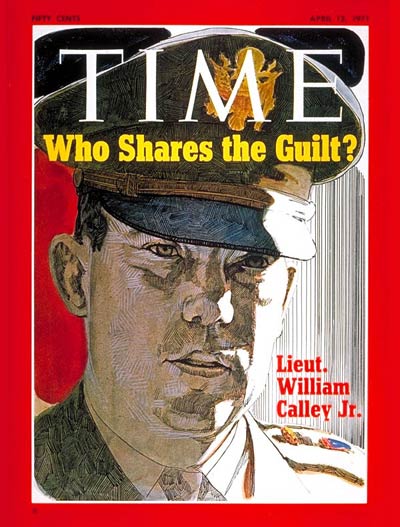

When Lt. William Calley was found guilty of murdering more than 20 Vietnamese civilians, it ended the argument that an American soldier could not have possibly done such a thing. But the verdict of Mar. 29, 1971, despaired hawks and doves alike.

Read more: Read the Letter That Changed the Way Americans Saw the Vietnam War

As TIME explained in a cover story about the trial, those who had believed Calley innocent “sought refuge in the oversimple conclusion that Calley was merely a scapegoat” or that “the Army sent Calley to Viet Nam to kill and should not punish him for doing precisely that.” On the other side, many of those who had no trouble believing that My Lai had happened were in agreement: accountability was key, they argued, but the finger should be pointed at the whole system, not Calley. Nobody was satisfied, though for starkly different reasons.

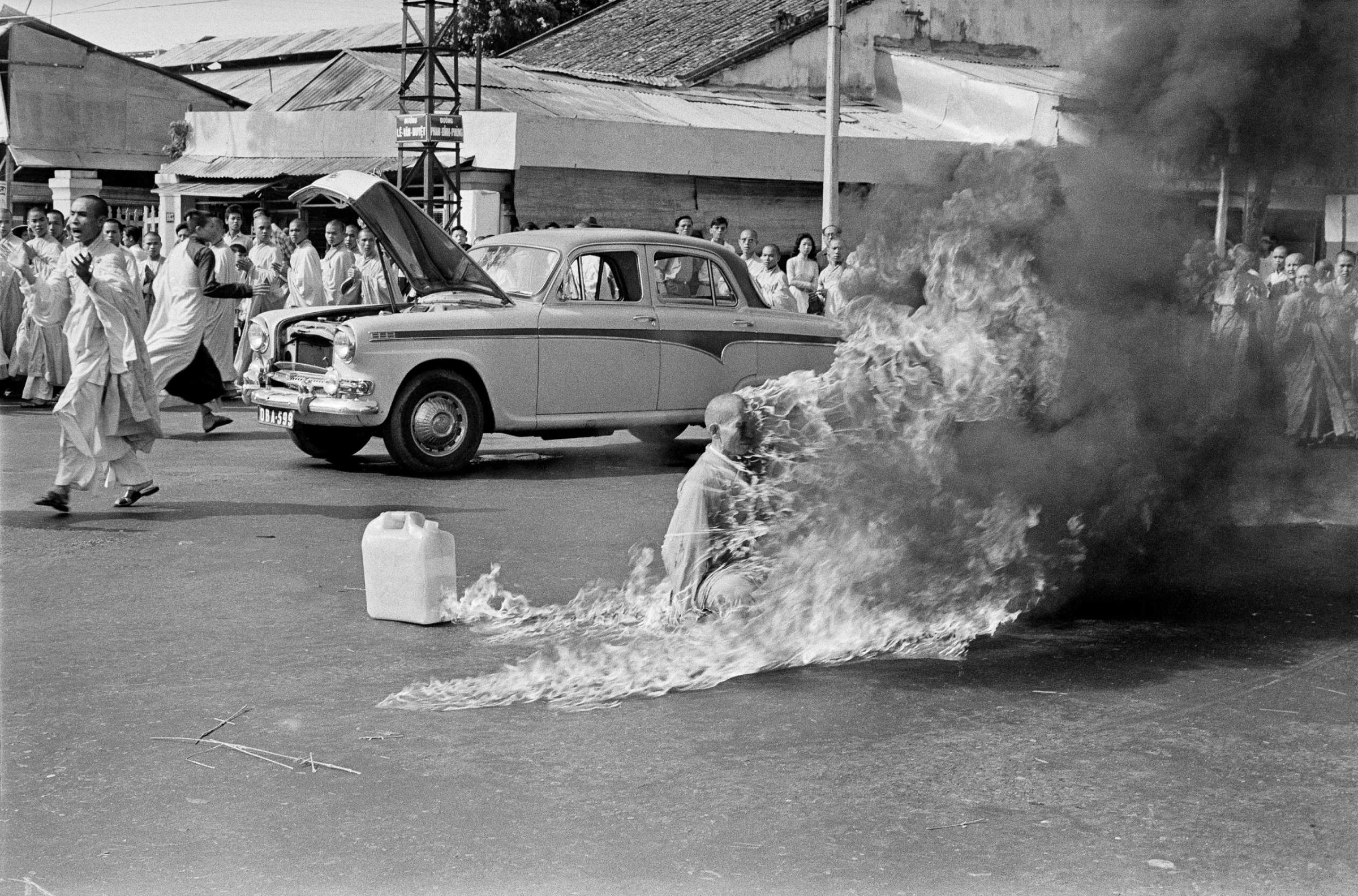

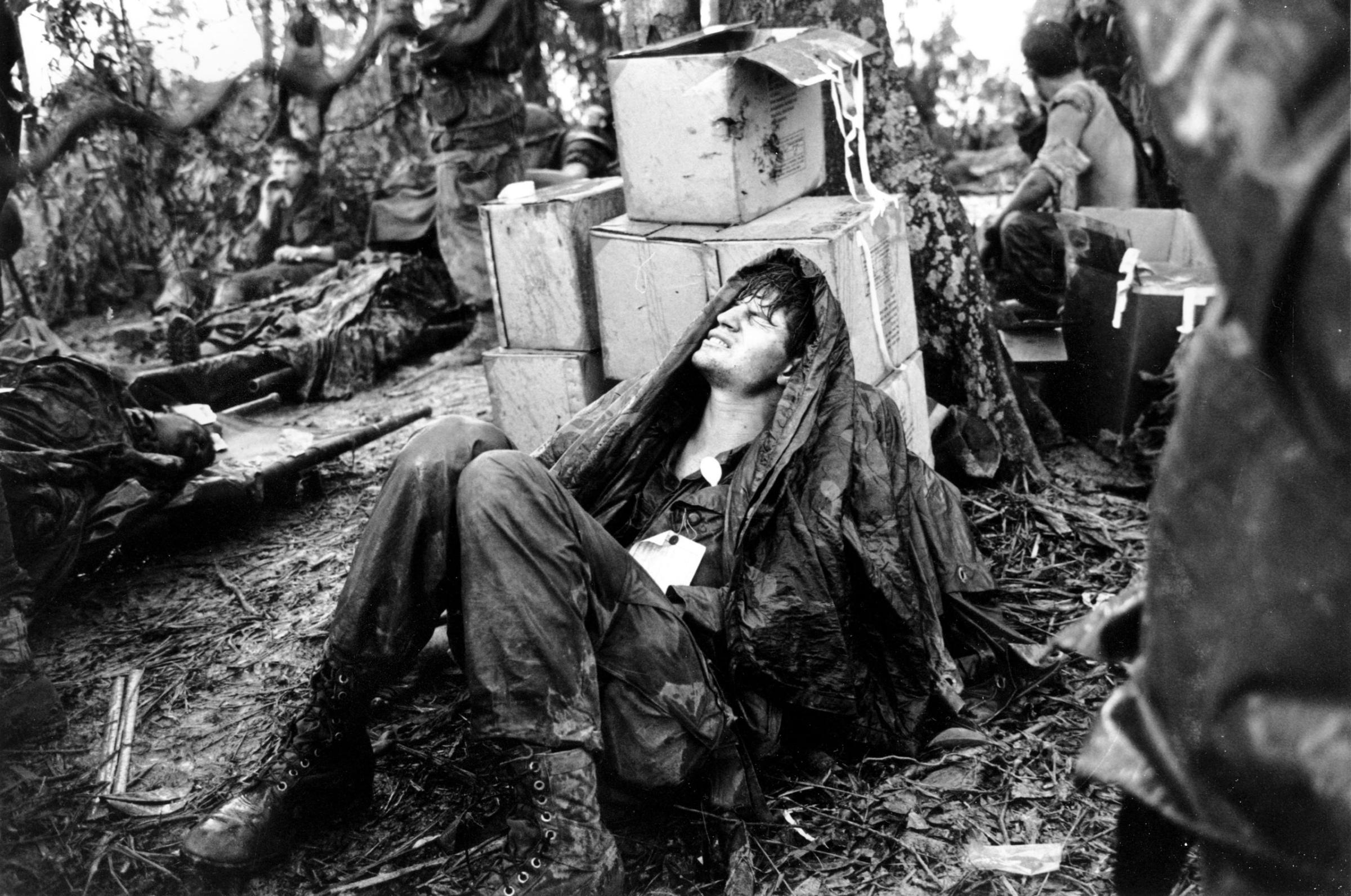

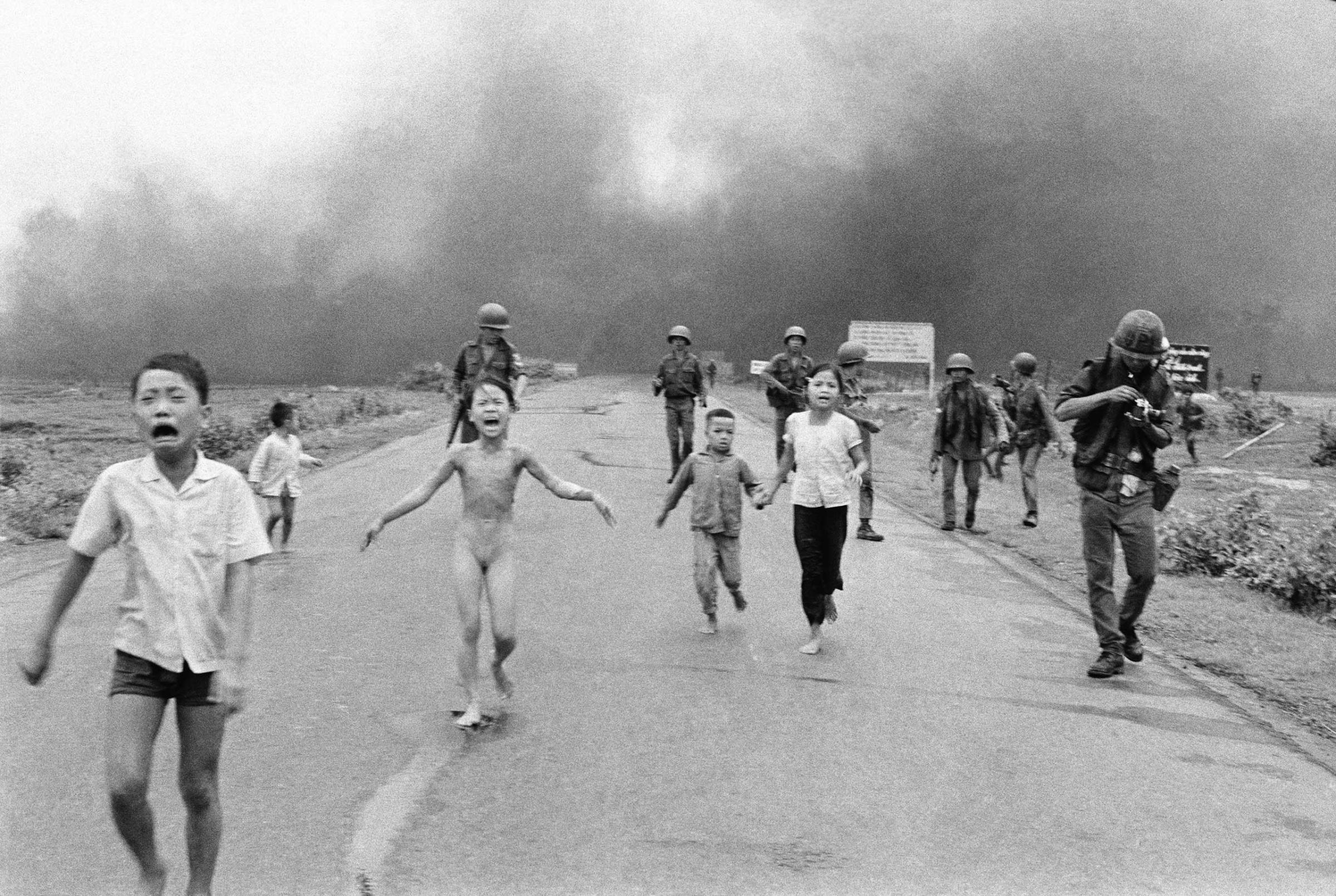

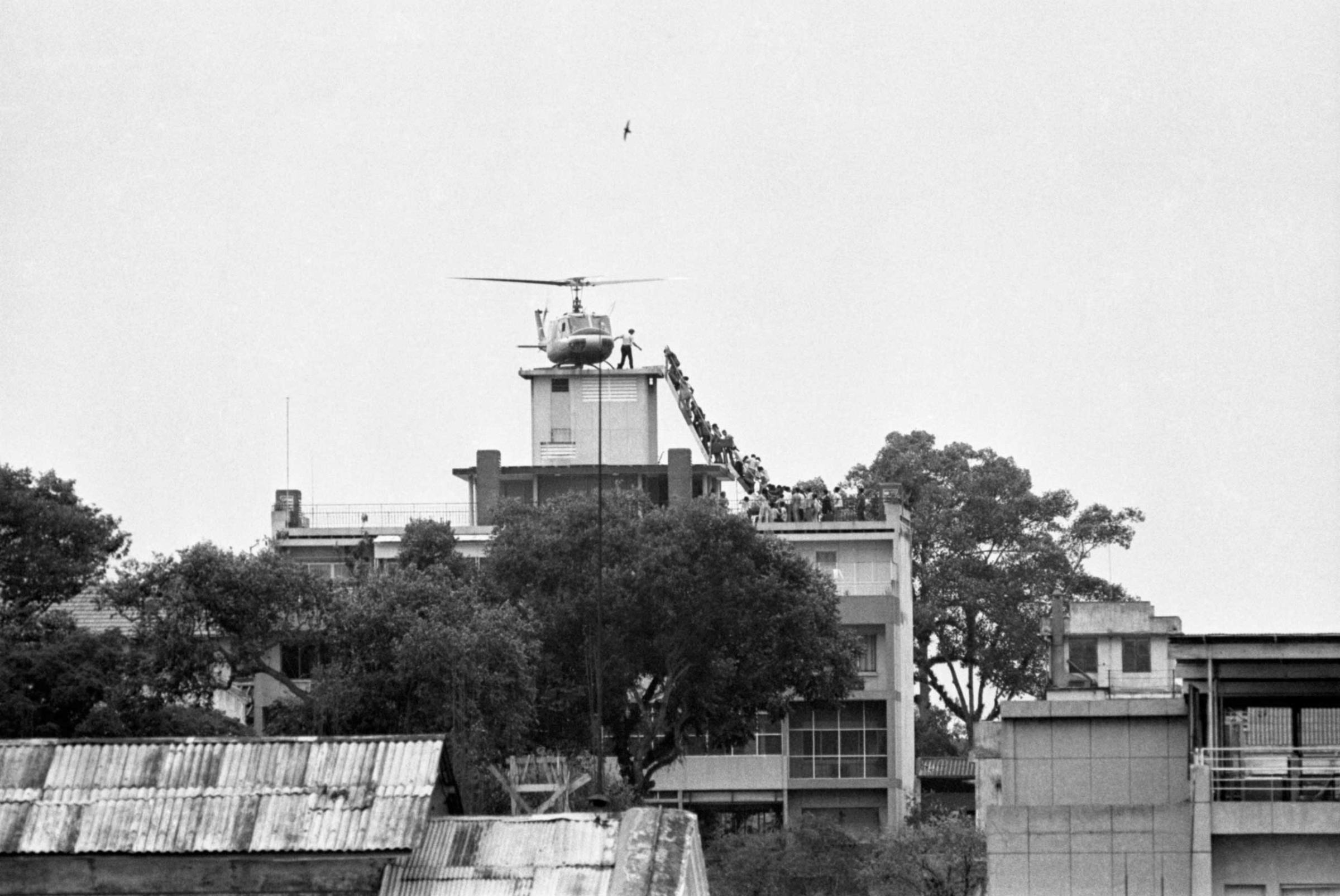

See the Most Iconic Photos of the Vietnam War

Nationwide, the indications of the split were many: protests (““We are all of us in this country guilty for having allowed the war to go on,” future Secretary of State John Kerry said at a protest. “We only want this country to realize that it cannot try a Calley for something which generals and Presidents and our way of life encouraged him to do”), flags flown at half-mast—even songs:

But TIME’s editorial stance on the matter was clear to see:

The tragic reality of My Lai and what it stands for is being avoided in two ways. One is by concluding that the fault is universal and therefore requires a universal bath of guilt, comforting in its generality. The other is by pretending that what happened was necessary and even commendable. The first view insists on the original sin of American Viet Nam policy and holds that Presidents should go to jail. Apart from having obvious legal flaws, the “we-are-all-guilty” position presents a moral trap: if everyone is guilty, no one is guilty or responsible, and the very meaning of morality disintegrates.

The other view, that Calley only did his duty, is equally untenable. It is one thing to sympathize with him or to hold that others are culpable as well; it is quite another to deny the difference between killing an armed guerrilla and mowing down old men, women and children. Even amid horror, distinctions must be made—that is the essence of law, morals and therefore survival. Not to make them is a form of moral blindness. That blindness and the attendant glorification of Lieut. Calley may well be the ultimate degradation of the U.S. by the Viet Nam War.

Major Brown, the pensive juror, believes that if the verdict is “tearing this country apart, it is good because maybe it will make [Americans] look within themselves to find out what’s wrong. I don’t think it will hurt the U.S.” Maybe not. Yet the crisis of conscience caused by the Calley affair is a graver phenomenon than the horror following the assassination of President Kennedy. Historically, it is far more crucial. Within its limits, the Warren Commission served to mute much of the national agitation that ensued after Kennedy’s death. Nixon has ruled out a Warren-style review of the Calley case itself, but there are suggestions inside the Administration and out that a comparably nonpartisan commission explore the whole question of American conduct of the Viet Nam War. Some Americans are skeptical; Harvard Sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset thinks that it would not reduce national tensions simply because “there are no neutral people left in the country.” Still, Americans must find some means of confronting what they have done to themselves in Viet Nam and what they will continue to do to themselves until U.S. involvement in Indochina finally, irrevocably and mercifully comes to an end.

See how LIFE reported on My Lai: American Atrocity

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com