As Donald Trump moves closer to the Republican presidential nomination, unhappy conservatives are contemplating a number of ways to stop him. Some are hoping to stop him at a contested convention in Cleveland in July. But a handful of others have set their sights even further off: In the House of Representatives after Election Day.

It sounds like an outlandish scenario ripped from a script for House of Cards or even Veep. But it’s actually happened before—twice.

The idea got a mainstream boost recently when former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg cited it as a reason he wouldn’t run for president as an independent and then when conservative blogger Erick Erickson told NPR that he believes the Republican Party ought to put its weight behind a third-party candidate in order to cause that outcome.

Erickson’s strategy is straightforward, if daunting in practice: The third-party candidate would run to win just enough states that they would deprive both Trump and the Democratic nominee from scoring the majority in the Electoral College (currently 270 electors).

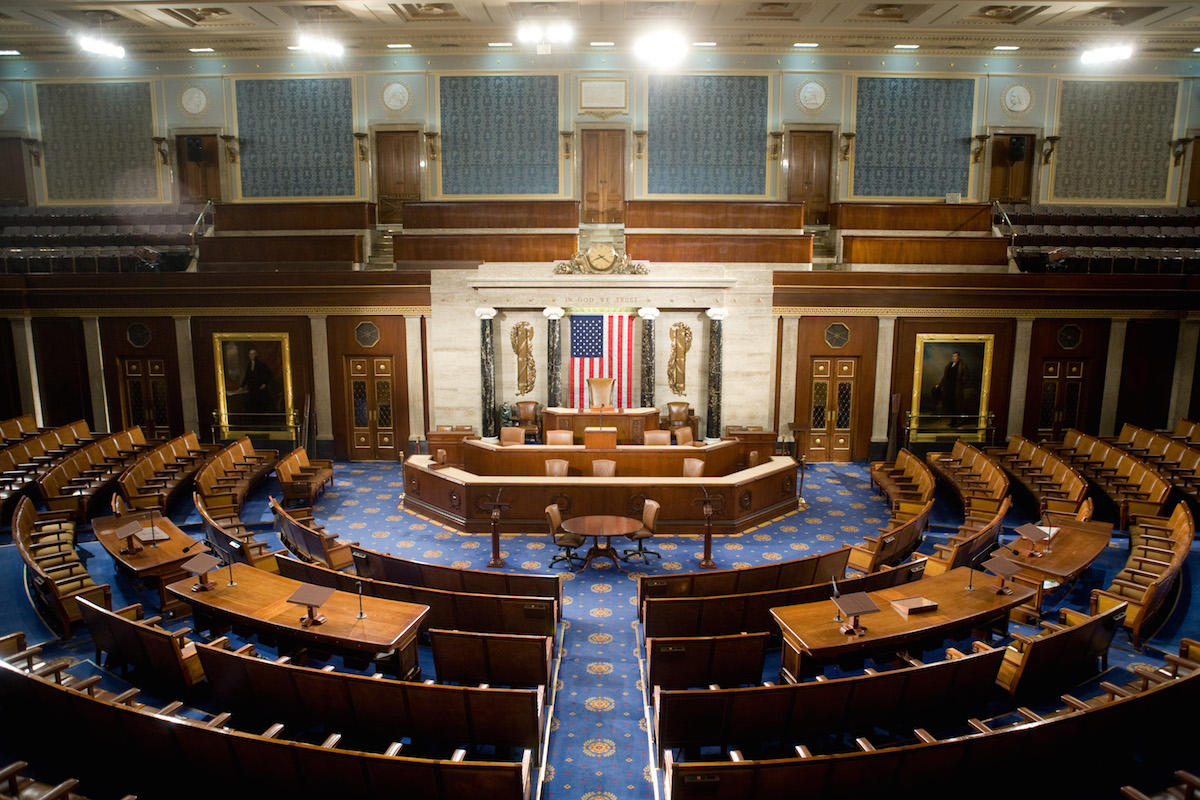

Under the Constitution, that would bump the election to the House of Representatives, which is currently controlled by Republicans, who Erickson presumes would choose the third-party candidate.

There are a host of logistical problems behind this scheme, as TIME’s Alex Altman has explained, including the typically difficult process of getting an independent candidate on the ballot in all 50 states, but that very situation arose during one of the first presidential elections in U.S. history.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

It’s called a “contingent election” and it was originally provided for in Article II of the Constitution. Under the original system, electors in each state cast two votes each, for president and vice president, with the top vote-getter becoming president and the runner-up being their vice president. Because the ballots didn’t distinguish between which candidate was supposed to be commander-in-chief, it was up to the political parties to ensure that at least one fewer vote went to the veep pick.

This next part will sound familiar to anyone who has binge-listened the soundtrack to Hamilton.

The system worked smoothly for the first three elections, with George Washington winning two terms and his vice president, John Adams, winning in 1796 on the Federalist ticket. But it was sorely tested in the election of 1800, when Adams ran for re-election against Thomas Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr, who represented the Democratic-Republican Party.

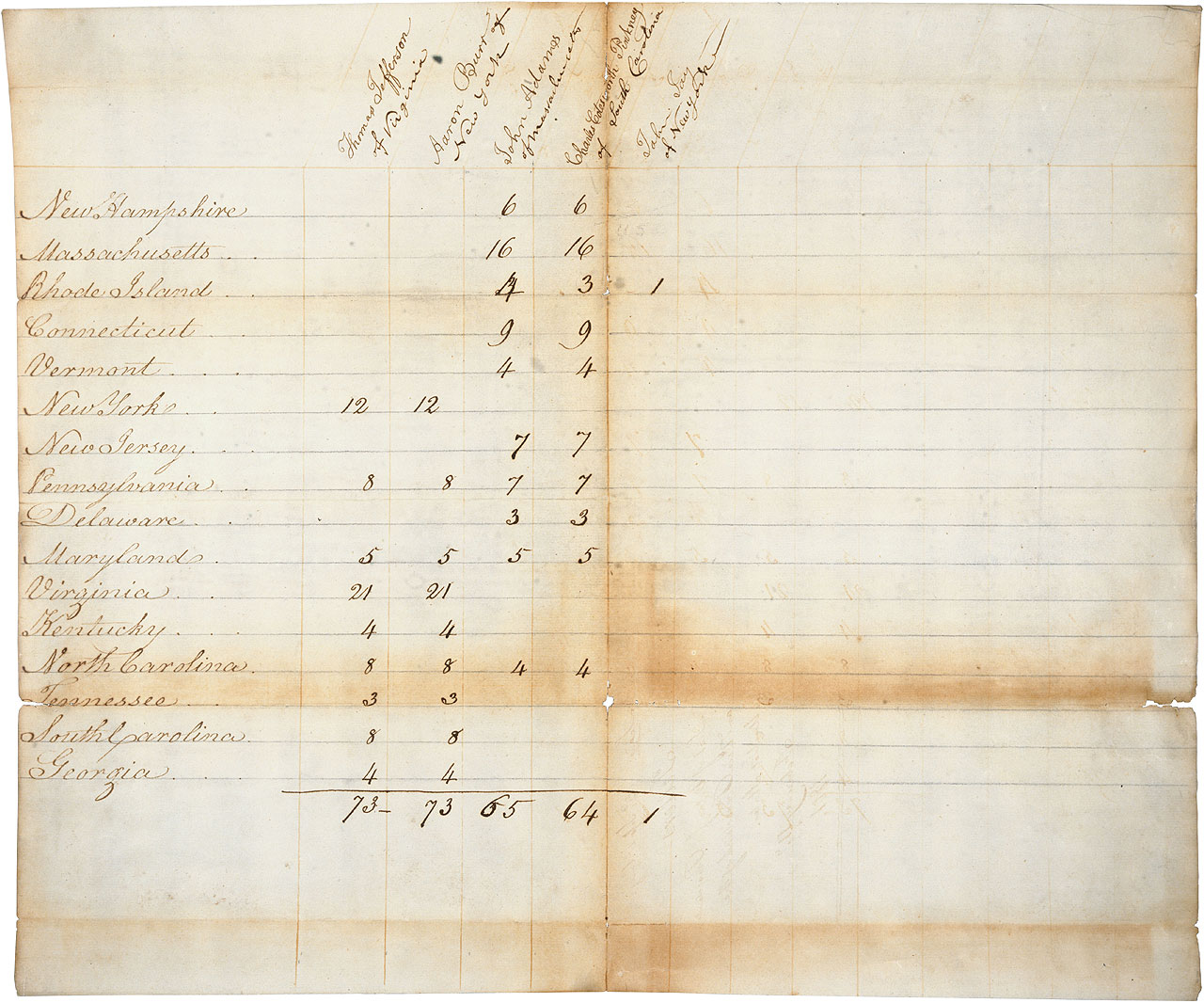

But the Democratic-Republicans neglected to ensure that Jefferson had at least one more vote than Burr, which meant that technically he and his running mate were tied, with 73 votes each.

Here’s the actual tally of votes, from the National Archives:

So the House—which was still dominated by Federalists—got to pick. It took dozens of ballots before, with the help of Alexander Hamilton’s influence, the Federalists opted for Jefferson and Burr became Vice President.

At that point, it was pretty obvious that this contingent election thing was going to be a problem. As a result, the 12th Amendment was added to the Constitution before the next Presidential election. Among other tweaks, it separated the Presidential and Vice-Presidential ballots into two separate categories. It also narrowed the number of people the House would choose from in a contingent election down to three, from five. (There are lots of other logistics involved, both before and after the amendment was passed, but those are the ones to pay attention to here.)

This new system would be put to the test in the election of 1824, when once again no candidate for President received the necessary majority. That year, Andrew Jackson won the Electoral College, but not with enough strength to clinch the majority. The first and second runners-up were John Quincy Adams, the eventual winner, and William Crawford. Henry Clay, who was Speaker of the House, was in fourth place—but because only the top three were eligible by that time, he was out.

Though Congress would intervene in elections a few more times, that year would be the last time the House of Representatives would select the President using this particular constitutional quirk.

The causes of that last contingent election shed light on the Republican hopes for this year: there were four serious contenders for the same office. Because they split the vote largely geographically, they each managed to win the electoral votes of a number of states, moving the contest to the House. But if a candidate doesn’t win any states, he or she can’t be considered for the House’s decision, so it can’t be an entirely last-minute decision.

What does that mean for 2016? If the Republican party wants to get an alternate candidate into the running, their goal should be to choose someone who can win a handful of states—rather than a more national candidate who might end up as a spoiler—and that person better get started sooner rather than later.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com