The Ides of March—Mar. 15 on our current calendar—is famous as the day Caesar was murdered in 44 BCE, but the infamy of the calendar date tends to obscure the actual history of what happened then. Few can give more than a couple of lines from Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar, in which the soothsayer tells the emperor to beware the date.

But how did Julius Caesar actually die?

Here’s what was going on in Rome at that time: the empire had faced a century of challenges and violence. Fighting (an eventually winning) the latest civil war only strengthened Caesar’s rule of Rome. At first he had been meant to be absolute ruler for one year. Then a decade. Soon enough, he was named dictator for life. “Rome had never had a dictator for life, much less a dictator for ten years, and people were very sensitive about that” says Barry Strauss, a professor of history and classics at Cornell University, and author of The Death of Caesar.

The ruler tried to convince the Roman people, particularly the nobility, to follow him—but it didn’t work. Rome’s elite reached the conclusion that Caesar’s real goal was to be “an uncrowned king of Rome,” Strauss says, and leave Rome’s traditional nobility “holding empty titles without real power.” Some even saw his affair with Egypt’s Queen Cleopatra and the recent adoption of a calendar based on Egypt’s as evidence he wanted a monarchy like Egypt’s.

A group of about 60 men began to plot how to rid Rome of Caesar. Many of the conspirators were trained military men who, according to Strauss, spent weeks, if not months, planning Caesar’s downfall. They were led by a group of three—including Marcus Brutus, of “Et tu, Brute” fame—whose individual motives went beyond a quest for liberty, Strauss argues. “The real Brutus” he says, “was a complex character, who yes, did care about liberty, but he also cared about the power and prestige of his own family,” as opposed to the idealistic hero of Shakespeare or Dante’s betrayer consigned to hell.

And yes, the deed did go down on the Ides of March.

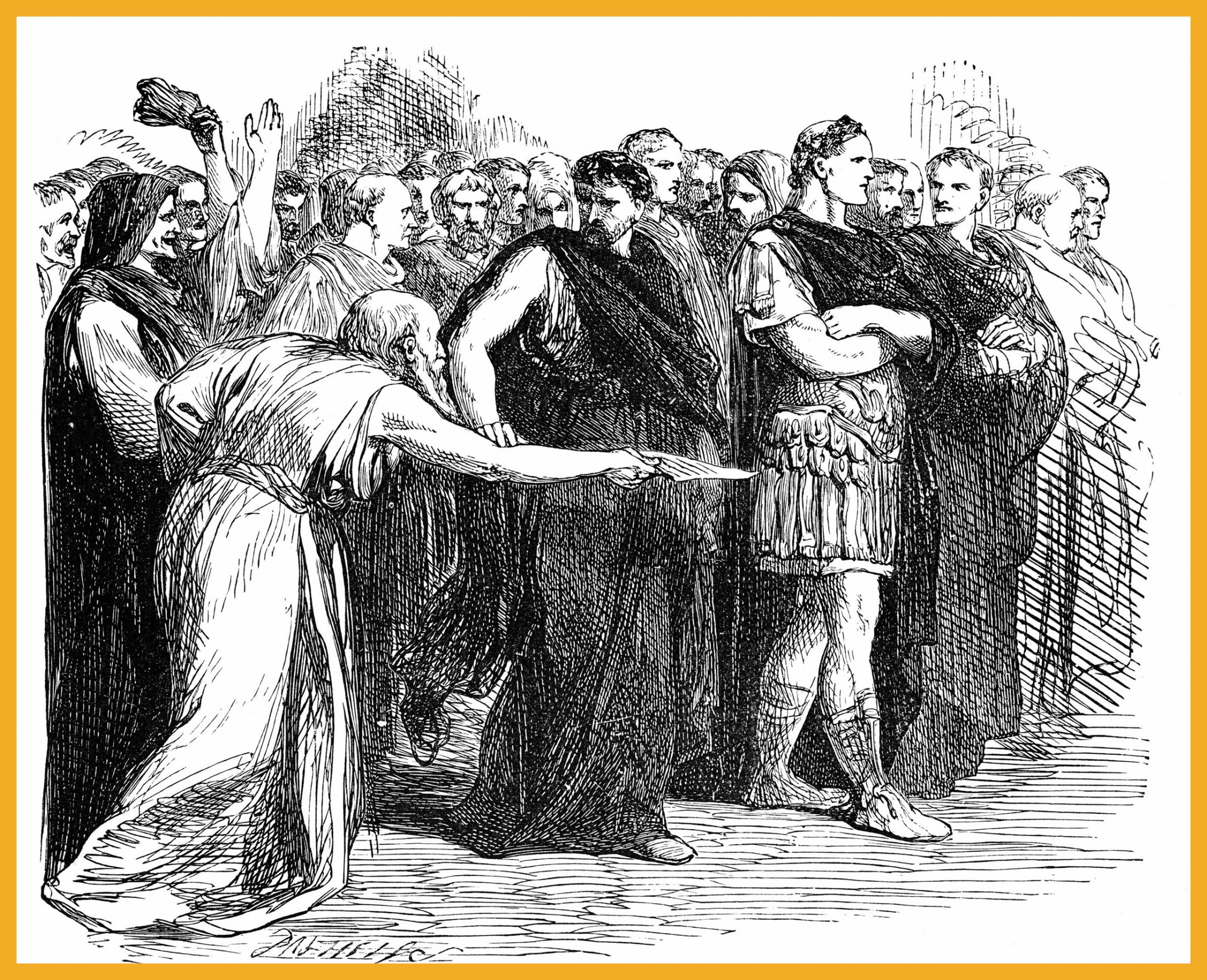

The reason was that the conspirators had a deadline: Caesar planned to leave Rome on Mar. 18 to settle some of his veterans in southern Italy before going east to begin a long campaign. If it didn’t happen before then, the chance would not come again soon and their plot could not be kept secret forever. That’s why, even though Caesar almost stayed home due to unfavorable omens and a spell of dizziness, one of his eventual assassins—Decimus, a close friend of his—convinced him it would be an insult to the Senate to not attend. Once there, with no bodyguards and with his friend Marc Antony waylaid by conspirators, he was attacked. Caesar was stabbed a total of 23 times. Once he died, the assassins marched to the Capitoline hill, a half mile away, along with a troop of gladiators. The gladiators, Strauss says, had been prearranged “to protect the conspirators in case there was any resistance to their effort.”

At this point, Strauss says, “the future of Rome is up for grabs.”

In the days that followed, the people of Rome gathered to listen to speeches from both sides, those who saw the conspirators as liberators and those who saw them as criminals. At first, a compromise was proposed: the assassins would get amnesty, but the laws that Caesar had passed as dictator would not be nullified by that recognition of his actions as an overstepping of power. The decision, Strauss says, was “peaceful but not particularly stable”—and by Caesar’s funeral on Mar. 20 it was already obsolete. After Marc Antony’s stirring pro-Caesar funeral speech a riot broke out, as depicted in Shakespeare’s play, and Caesar’s body was burned in the forum. The image of the conspirators as “misguided liberators, somehow representing everything that was good about the Roman spirit” persisted over the years, Strauss says, but the reality is more complicated.

The riot wasn’t even the real turning point, he believes. Instead, Brutus’ failure to ingratiate himself to Caesar’s military would reverberate throughout the rest of the empire’s history. The fighting and kaleidoscope of shifting alliances that followed the assassination led to decades of conflict. By the time the dust cleared, the Roman emperor had more power than ever.

“It’s tremendously ironic because the assassins think that they’re going to save the Roman republic, but in fact it turns out to be completely opposite,” Strauss says. “They set in motion 15 years of events which cement the Roman empire and turn Rome permanently into a monarchy.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com