Though the theremin now holds its own in the world’s musical history, made famous by its trademark sound as used by bands like the Beach Boys, it started its life as more of a scientific toy than a musical instrument.

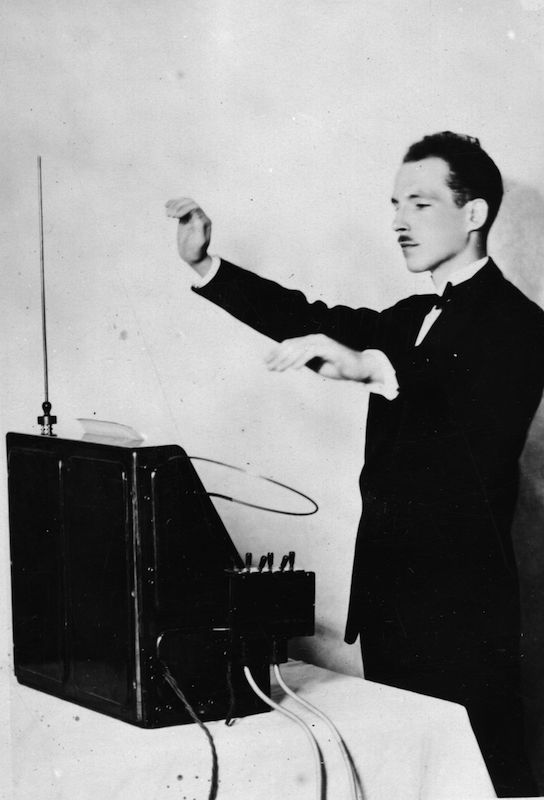

As TIME explained in 1928, the invention then being toured around by Professor Leon Theremin, pictured here, was basically a radio. The current inside its base alternated so quickly that the oscillations couldn’t be picked up by human ears; like a radio hobbyist, Theremin had figured out how to cancel out the waves so that only an audible amount remained. “And just as a radio amateur can make a cheap receiving set squeal by moving his hand about the unprotected parts and thus altering the electrical tension of the whole set,” the magazine noted, “just so Professor Theremin altered the electro tension of the electro-magnet fields within his box. The precision with which he built his contrivance permitted him to extract, not amateur squeals, but harmonious musical sounds.”

But just because the device could be played like an instrument didn’t mean it was easy.

On one hand—no pun intended—the lack of division between notes allowed a much wider range of sounds to be created: rather than skipping from, say, C to B, a theremin player could capture every sound in between. On the other hand, the obvious challenge is the lack of frets or strings or keys that would ordinarily guide a musician. “How to train the human hand to such precision that it could pick correct notes unerringly from midair,” TIME would ask later in 1928, “where inaccuracy of a fingernail’s breadth, or even taking a deep breath at the wrong instant, would register a tonal error?”

Few people proved that such skill was possible as handily—again, no pun intended—as Clara Rockmore did. The theremin expert, who was born 105 years ago on Mar. 9, 1911, in Russia, met Professor Theremin right around the time that her career as a violinist was coming to an end. Theremin eventually sold the patent on his invention to RCA, and it was one of those models that Rockmore first used, according to the Nadia Reisenberg & Clara Rockmore Foundation. Later, however, Theremin made her a “more precise and responsive instrument” modified to her specifications.

The result was even more difficult to play well, but Rockmore found that it allowed for greater artistry. The result was certainly impressive:

“A lot of trial and error went into it,” she would later recall, “but the theremin saved my musical sanity by giving me an outlet in music.”

Rockmore, however, did not always get the recognition she deserved: in 1932, TIME reported on a concert at Carnegie Hall in which Leon Theremin wowed the crowd with a dance floor rigged up with his technology, so that the whole area became a theremin to be played with the body. The person who demonstrated was, according to the magazine, an unnamed “lady-pupil” of the scientist’s. That pupil was, according to Carnegie Hall records, one Clara Reisenberg—or, as she was better known after her marriage, Clara Rockmore.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com