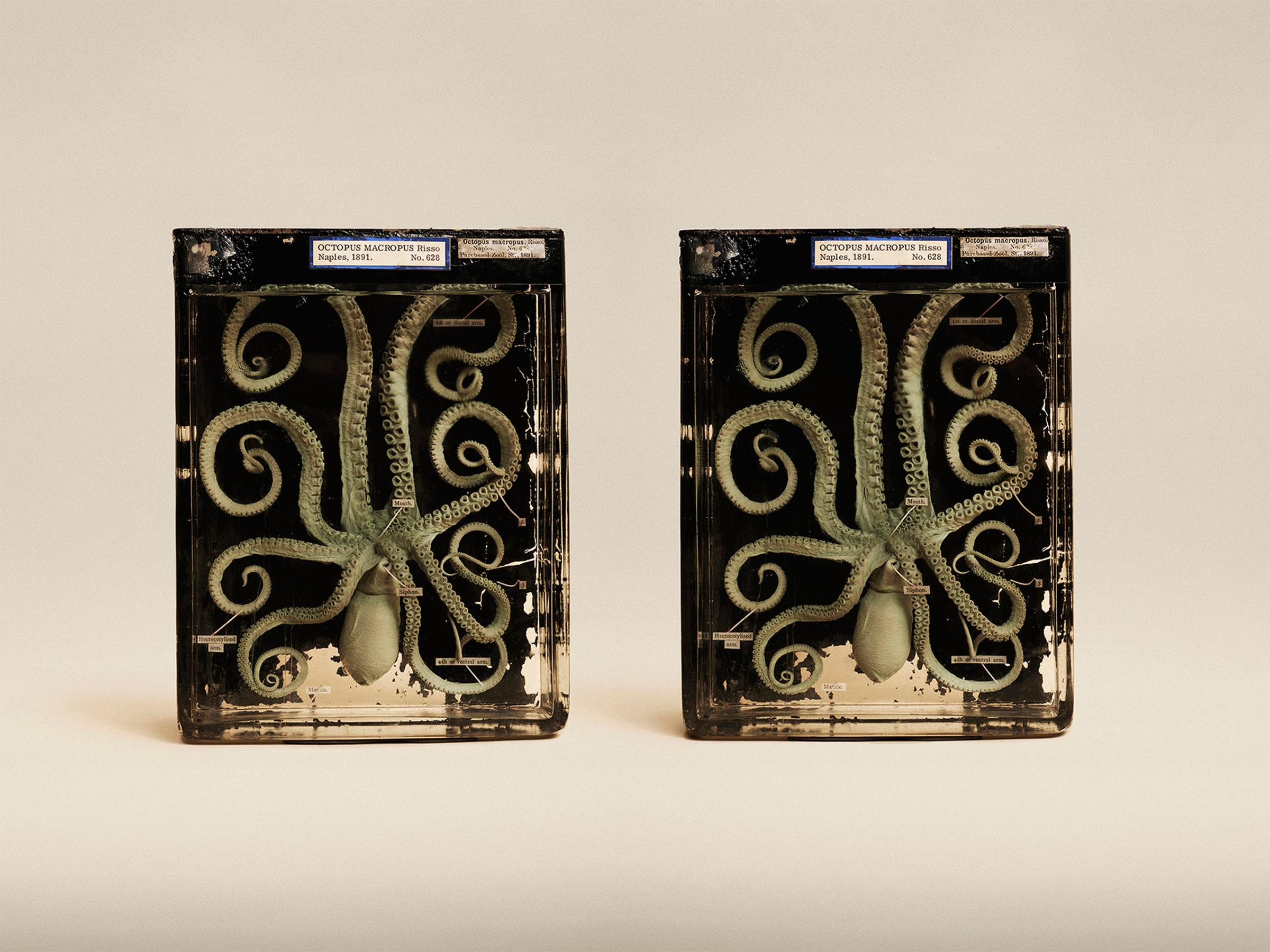

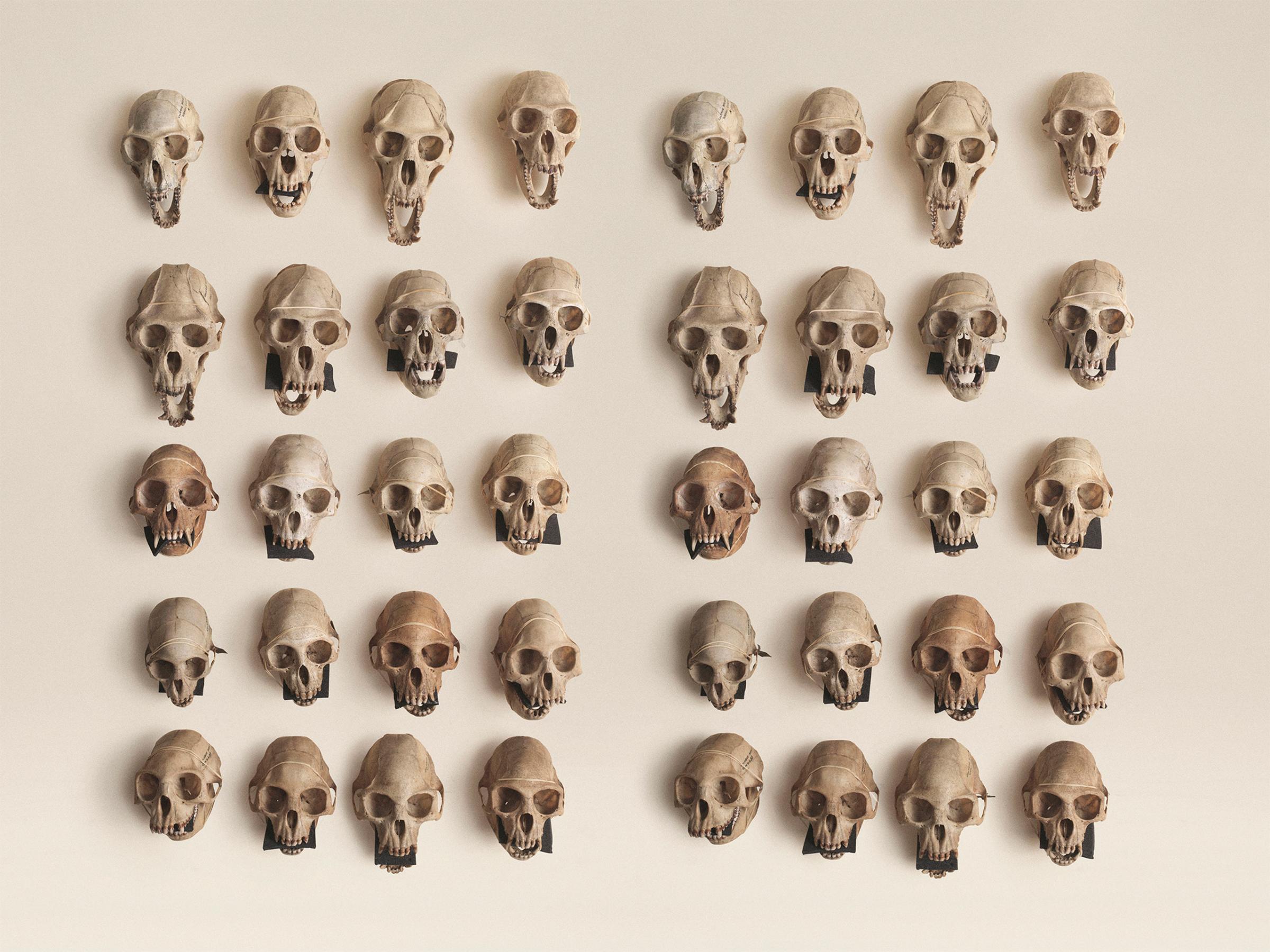

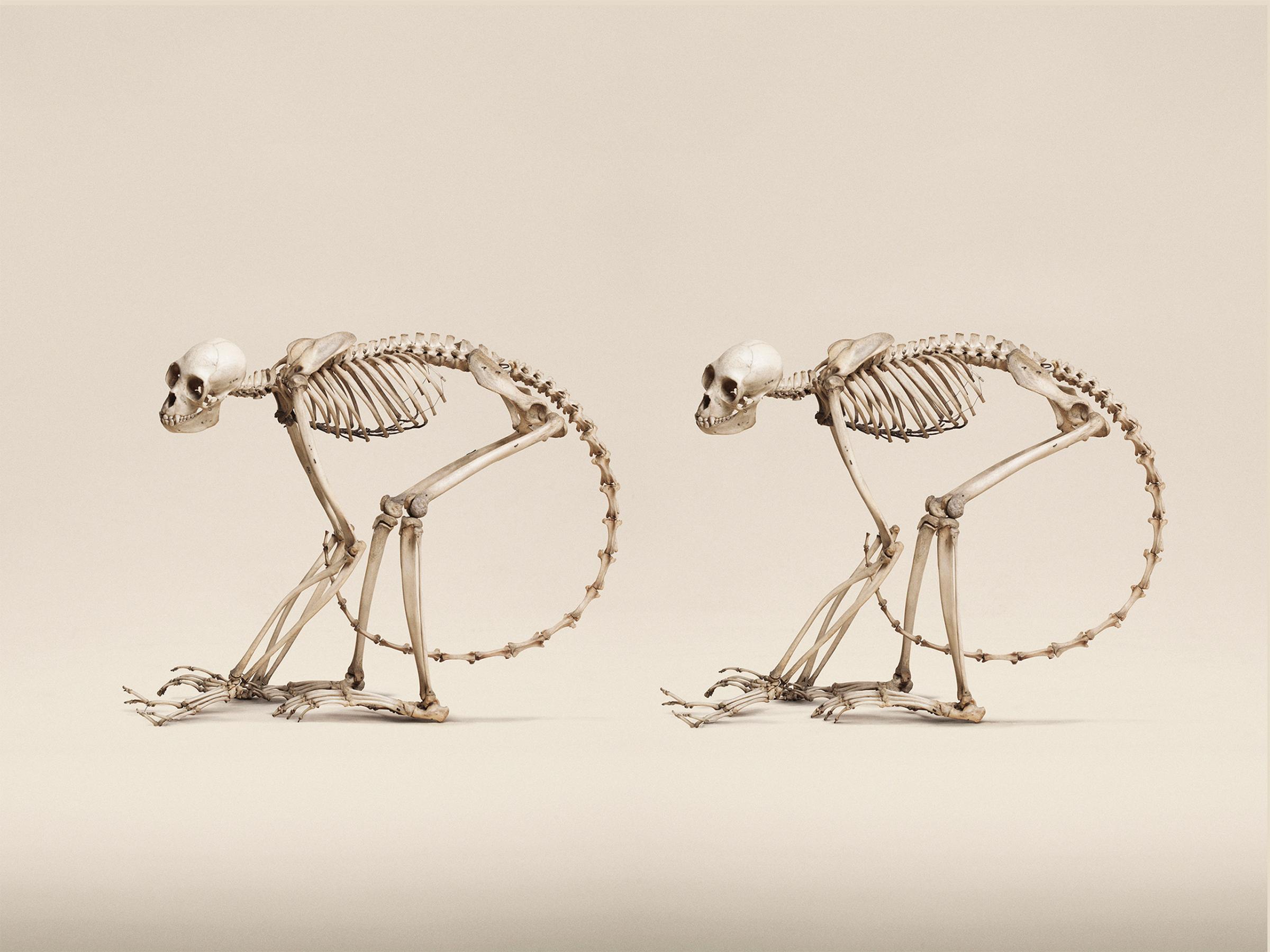

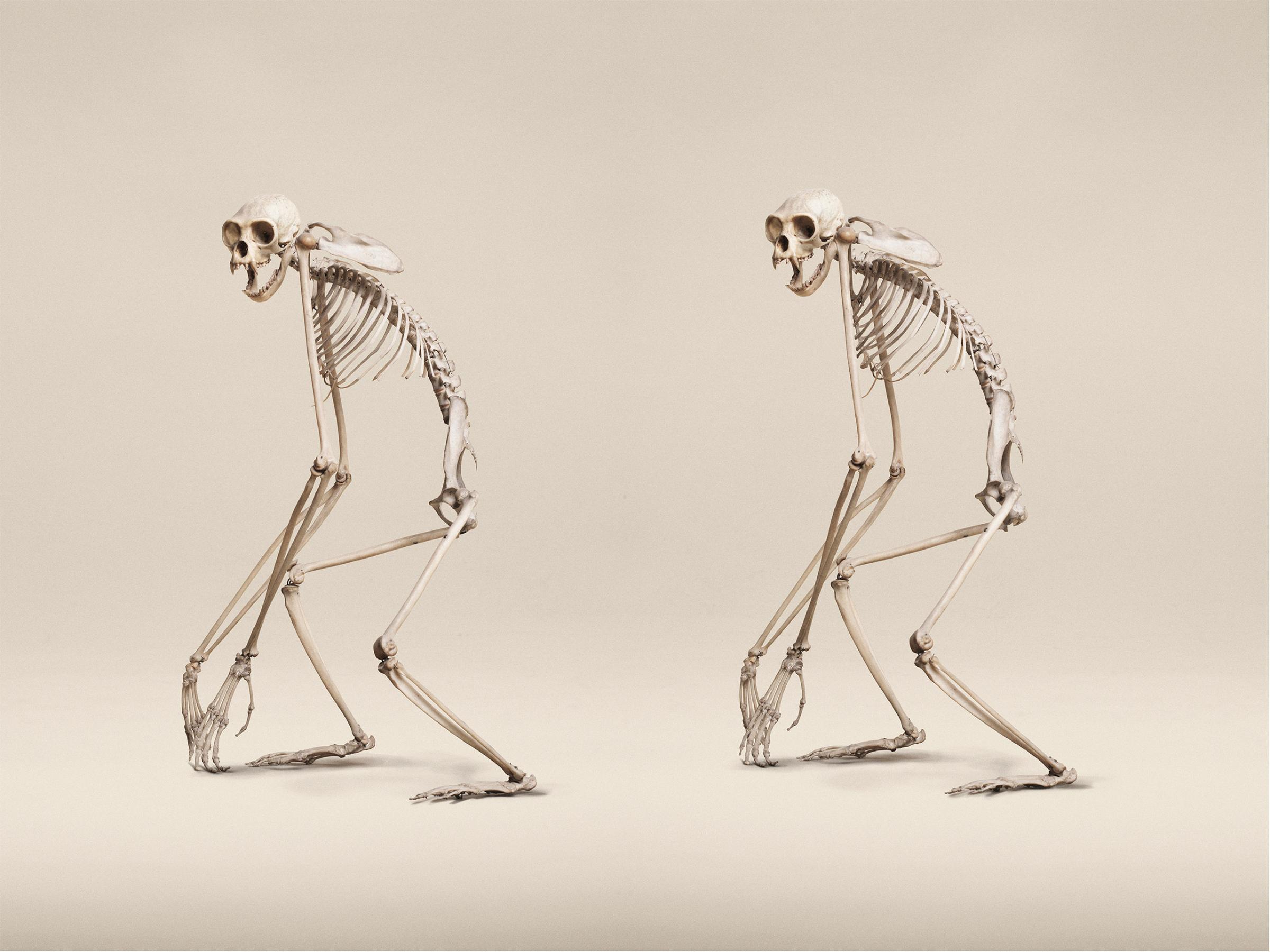

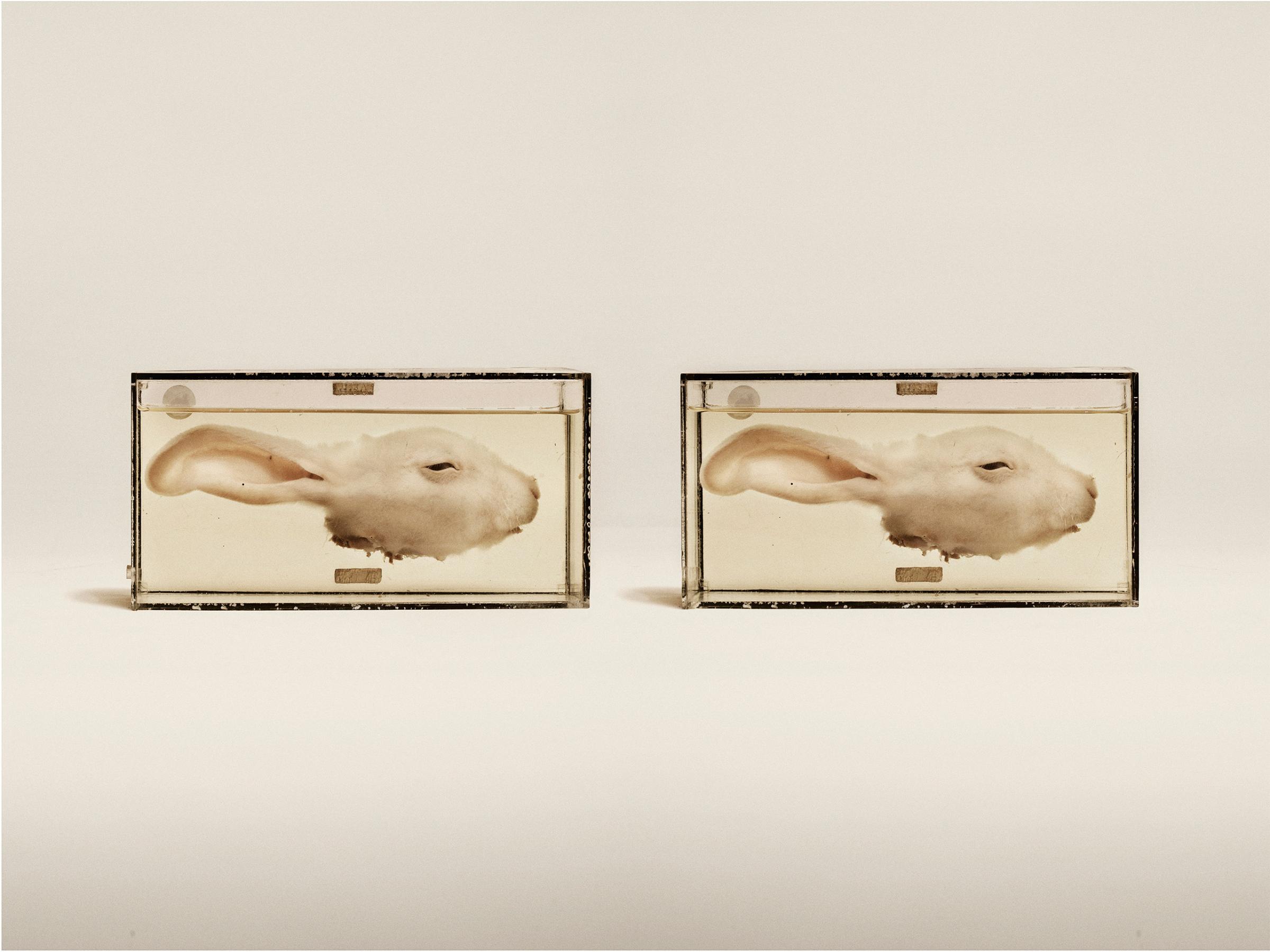

They sit in the storage rooms of grand museums, guarded remains of once-living creatures now frozen in time. They almost seem alive, skeleton frames posing behind a plate a glass: The spider monkey looks impish; the Atlantic Octopus enlarges in rage; the Juvenile Chimpanzee hunches over like an old man; while the Leafy Sea Dragon coyly flaunts its fins.

“It’s interesting how skeletons and specimens in fluid can retain or reflect a character,” photographer Jim Naughten tells TIME.

Naughten’s Animal Kingdom, currently on show at Klompching Gallery in New York, has been described as an attempt to reanimate history. Through stereoscopy—a technique developed in the 1800s to create the illusion of viewing images in three dimensions—viewers explore images of Victorian and Edwardian Natural History specimens as if looking through a microscope.

Naughten discovered stereoscopic photography while researching a World War I project. “I was instantly smitten,” he says. “It was extraordinarily profound to be able to witness three dimensional impression of a war which took place a hundred years ago in this way. I wanted to see if it was possible to make stereo prints, and then set about finding a subject that I wanted to explore that would suit the treatment. The natural history specimens were perfect.”

He spent a year in the archive rooms of the Grant Museum of Zoology, Oxford Museum of Natural History, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, among many others. After culling images taken on a phone, he photographed each specimen in a make shift studio. Post production then involved retouching, positioning, sizing and matching up with the viewer distance.

Naughten was struck by the complex relationship between ourselves and the animals, which he observed through the treatment of the specimens. While working at Oxford Natural History museum, he was informed by an incensed zoologist that it was illegal to keep human and ape remains in the same room, even though we are both primates.

“Working on the project has brought in to focus some big questions,” he says. “Namely, our complicated relationship with the animal kingdom and how we see ourselves as separate and consequently our own history of human evolution.”

Jim Naughten‘s work in on show at the Klompching Gallery in New York until May 28, 2016. The show will also be on view at KK Outlet in London until May 14. A monograph of the work will be published and distributed by Prestel next month.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com