The nature of the threat in the new J.J. Abrams-produced thriller 10 Cloverfield Lane is super secret, but the story of a group of people trying to stay safe in an isolated shelter calls to mind a very real time in American history when the threat was anything but vague. In the early 1960s, average citizens of all means scrambled to build shelters that might protect them from the most pressing fear of their Cold War age: nuclear war.

Fallout shelters were, at first, a fringe idea with limited mainstream support. It was acknowledged by the mid-1950s that blast shelters—structures that would protect a large number of people near ground zero of a nuclear attack—were pretty much pointless, but that it might be possible to protect citizens from fallout so that, after some period of time, they might be able to emerge and rebuild in the area near the attack. Though some prominent figures (notably New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller) advocated for a national shelter-building program, both to save lives and on the idea that potential survival would deter the USSR from trying to wipe out the U.S. in one go, others didn’t trust the shelters to work or believed the run-and-hide mentality was un-American.

In the summer of 1961, that situation swiftly changed.

It wasn’t that the pro-shelter voices suddenly convinced the nation to listen up, but that the fear of needing one became suddenly much more acute. For one thing, the concentrated Cold War crisis over the relationship between the East Berlin and West Berlin—which culminated that summer in the surprising construction of the Berlin Wall—showed the world that the Soviets were capable of taking drastic measures. And perhaps more importantly, on July 25 President Kennedy took to the airwaves to update the nation on what was happening there and, in the process, left the nation severely freaked out. “The immediate threat to free men is in West Berlin,” he said. “But that isolated outpost is not an isolated problem. The threat is worldwide.” Kennedy announced that he was expanding the size of the U.S. military and its missile power, and that he was taking steps to speed up that change. But the military wouldn’t be the only group that would bear a burden, he continued:

We have another sober responsibility. To recognize the possibilities of nuclear war in the missile age, without our citizens knowing what they should do and where they should go if bombs begin to fall, would be a failure of responsibility. In May, I pledged a new start on Civil Defense. Last week, I assigned, on the recommendation of the Civil Defense Director, basic responsibility for this program to the Secretary of Defense, to make certain it is administered and coordinated with our continental defense efforts at the highest civilian level. Tomorrow, I am requesting of the Congress new funds for the following immediate objectives: to identify and mark space in existing structures—public and private—that could be used for fall-out shelters in case of attack; to stock those shelters with food, water, first-aid kits and other minimum essentials for survival; to increase their capacity; to improve our air-raid warning and fallout detection systems, including a new household warning system which is now under development; and to take other measures that will be effective at an early date to save millions of lives if needed.

In the event of an attack, the lives of those families which are not hit in a nuclear blast and fire can still be saved–if they can be warned to take shelter and if that shelter is available. We owe that kind of insurance to our families—and to our country.

The year of the fallout shelter had begun.

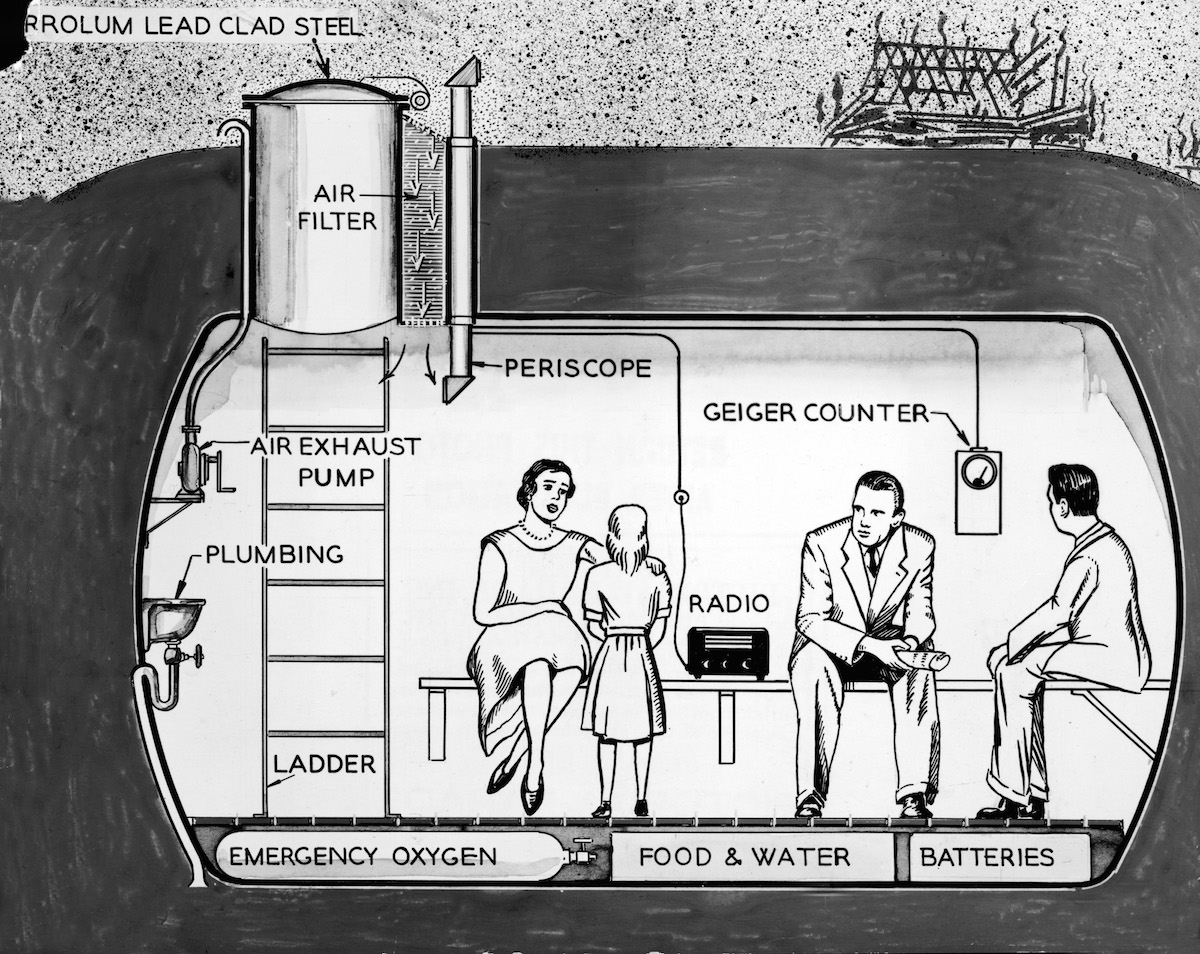

As TIME—which generally took a rah-rah tone on shelter-building—tracked the trend over the next months, a major public effort began to mark and equip existing public shelters and encourage individuals to build their own versions. A Gallup poll that August revealed that 3 million families had made changes to their homes for the purpose of protection, and another 9 million had stocked up on food. Some builders reported being overwhelmed by orders for shelters that would meet Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization standards: concrete or metal, under either three feet of soil or two feet of concrete or three inches of lead, with enough space for its occupants. A Department of Defense booklet about preparation was a runaway hit. Though it could be expensive to get a regulation prefab shelter installed, many people made do with simple DIY options.

By early 1962, however, doubts were beginning to creep in. The most acute fear of the Berlin crisis days had passed, and scientists were increasingly questioning the utility of the fallout shelters Americans had rushed to build. Furthermore, though the government had told citizens that they’d be able to leave their fallout shelters a fortnight after an attack, scientists announced that actually survivors might have to wait underground for months in order to emerge safely, particularly as the power and number of nuclear weapons in the world increased. And perhaps not incidentally, the surplus of shelters and related equipment caused a glut in the market, and it was no longer quite so profitable to get into the fallout shelter game.

About a year after it began, the height of shelter mania was over. But the idea of a backyard bunker would prove to have enduring power in American culture, and those shelter that had been built already would, in many cases, remain—the perfect place to hide from…something.

Read TIME’s 1961 cover story about civil defense, here in the TIME Vault: SHELTERS: How Soon, How Big, How Safe

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com