A new book, Photographs Not Taken, conceived and edited by photographer Will Steacy compiles personal essays written by more than 60 photographers about a time when they didn’t or just couldn’t use their camera.

The book, released by Daylight, is a fascinating compilation by a wide cross-section of image makers from around the world and is often filled with thoughts of regret, restraint and poignant self-realizations.

On the eve of the one-year anniversary of Tim Hetherington’s tragic death in Misrata, Libya, we present one of the most eloquent chapters from the book, in which the photographer offers his thoughts on depicting the dead in photographs and the questioning moment he had after making a picture of a dead soldier in Afghanistan:

There are many reasons not to take a picture—especially if you find the act of making pictures difficult. I was not brought up with a camera, I had no early fascination for pictures, no romantic encounters with the darkroom—in fact I didn’t become a photographer until much later on in life when I came to realize that photography—especially documentary photography—had many possibilities. One thing for sure was that it would make me confront any inherent shyness that I might feel. It did, but I still find making pictures difficult, especially negotiating and confronting “the other,” the subject, and dealing with my own motivations and feelings about that process.

This personal debate about making pictures was particularly apparent during the years I lived and worked in West Africa. In 2003 I lived as one of the only outsiders with a rebel group that was attempting to overthrow then-President Charles Taylor. It was a surreal experience—cut off and living in the interior of the country, I accompanied a rag-tag army of heavily armed young men as they fought their way from the interior forest into the outskirts of the capital, Monrovia. Reaching the edges of the city was an exhilarating experience after weeks of living in a derelict front-line town with little food. At one point, the rebels took over the beer factory and, after liberating its supplies, turned part of the facility into a field hospital where people with gunshot wounds were treated with paracetamol. Outside the factory compound lay about five bodies of people who, from the look of things, had been executed. A number had their hands tied behind their backs and most had been shot in the head and, despite the graphic nature, I had no qualms about making some photographs of these people.

Not long after, government forces counterattacked to push the rebels out of the city. Everyone was exhausted from the lack of sleep and constant fighting, and the retreat quickly turned into a disorganized scramble to get out of the city. Soldiers commandeered looted vehicles, and I even remember one dragging a speedboat behind it in the stampede to escape. To make matters worse, government soldiers were closing in on the escape route and began firing from different directions on the convoy of vehicles. One rocket-propelled grenade took out a car behind ours, and at one point we abandoned our vehicles and took shelter in a nearby group of houses. I began seriously considering abandoning the rebels and heading out on my own toward the coastline on foot, but luckily thought better of it and got back inside the car with the group I was with.

The road slowly wound its way away from the low-slung shacks of the suburbs and back into the lush green forest. Our close-knit convoy started to thin a little as some cars sped out ahead while others, laden with people and booty, took their time. The landscape slid by as I tried to come down and calm my mind from the earlier events—I was in a heightened state of tension, tired, hungry, and aware that I was totally out of control of events. Just as I started to feel the euphoria of being alive, our car slowed in the commotion of a traffic jam. A soft-topped truck up ahead that was carrying about 30 civilians had skidded as it went around a corner and turned over on itself. A number of people had been killed and wounded—probably having the same thoughts of relief that I had before calamity struck. Now they were dead and their squashed bodies were being carried out from the wreckage. Someone asked me if I was going to photograph this—but I was too far gone to be able to attempt any recording of the event. I couldn’t think straight, let alone muster the energy needed to make a picture. I just watched from a distance as people mourned and carried away the dead. My brain was like a plate of scrambled eggs.

There isn’t much more to add, but I always remember that day and the feeling of being so empty—physically, mentally, and spiritually—that it was impossible to make the photograph.

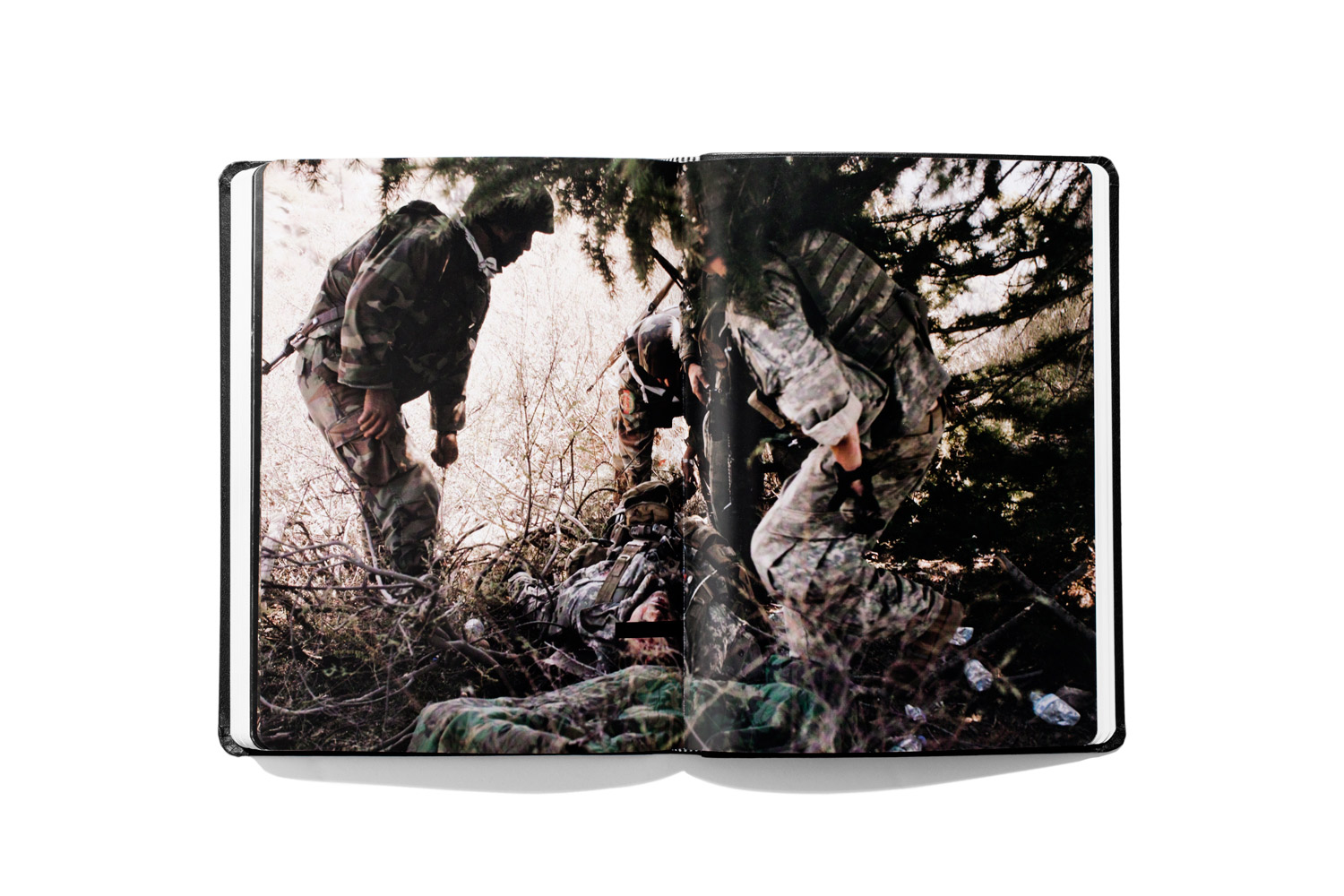

Years later, when I put together a book about those events in Liberia, I included a photograph of one of the people who had been killed outside of the beer factory. I thought it was an important picture but didn’t dwell on what it might mean for the mother of that boy to come across it printed in a book. My thoughts about this resurfaced recently as I put together a new book about a group of American soldiers I spent a lot of time with in Afghanistan. They reminded me a lot of the young Liberian rebel fighters, and yet, when I came to selecting a picture of one of their dead in the battlefield, I hesitated and wondered if printing a graphic image was appropriate. It was an image I had made of a young man shot in the head after the American lines had been overrun—not dissimilar from the one in Liberia. My hesitation troubled me. Was I sensitive this time because the soldier wasn’t a nameless African? Perhaps I had changed and realized that there should be limits on what is released into the public? I certainly wouldn’t have been in that questioning position if I’d never taken the photograph in the first place….but I did, and perhaps these things are worth thinking about and confronting after all.

—Tim Hetherington

Tim Hetherington (1970-2011) was a British-American photographer and filmmaker. His artwork ranged from digital projections and fly-poster exhibitions to handheld-device downloads. Hetherington published two monographs, Long Story Bit by Bit: Liberia Retold (Umbrage Editions, 2009), and Infidel (Chris Boot, 2010). His Oscar-nominated film Restrepo, about young men at war in Afghanistan, was also released in 2010. Tragically, Hetherington was killed while covering the 2011 Libyan civil war.

Photographs Not Taken also features work by Roger Ballen, Ed Kashi, Mary Ellen Mark, Alec Soth, Peter van Agtmael and many others. More information about the book and how to purchase it is available here.

On April 22, 2012 from 2:00-4:00pm, MoMA PS1, located in Queens, NY, will host a a panel discussion with contributors Nina Berman, Gregory Halpern, Will Steacy, Amy Stein, moderated by Daylight founders Michael Itkoff and Taj Forer.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com