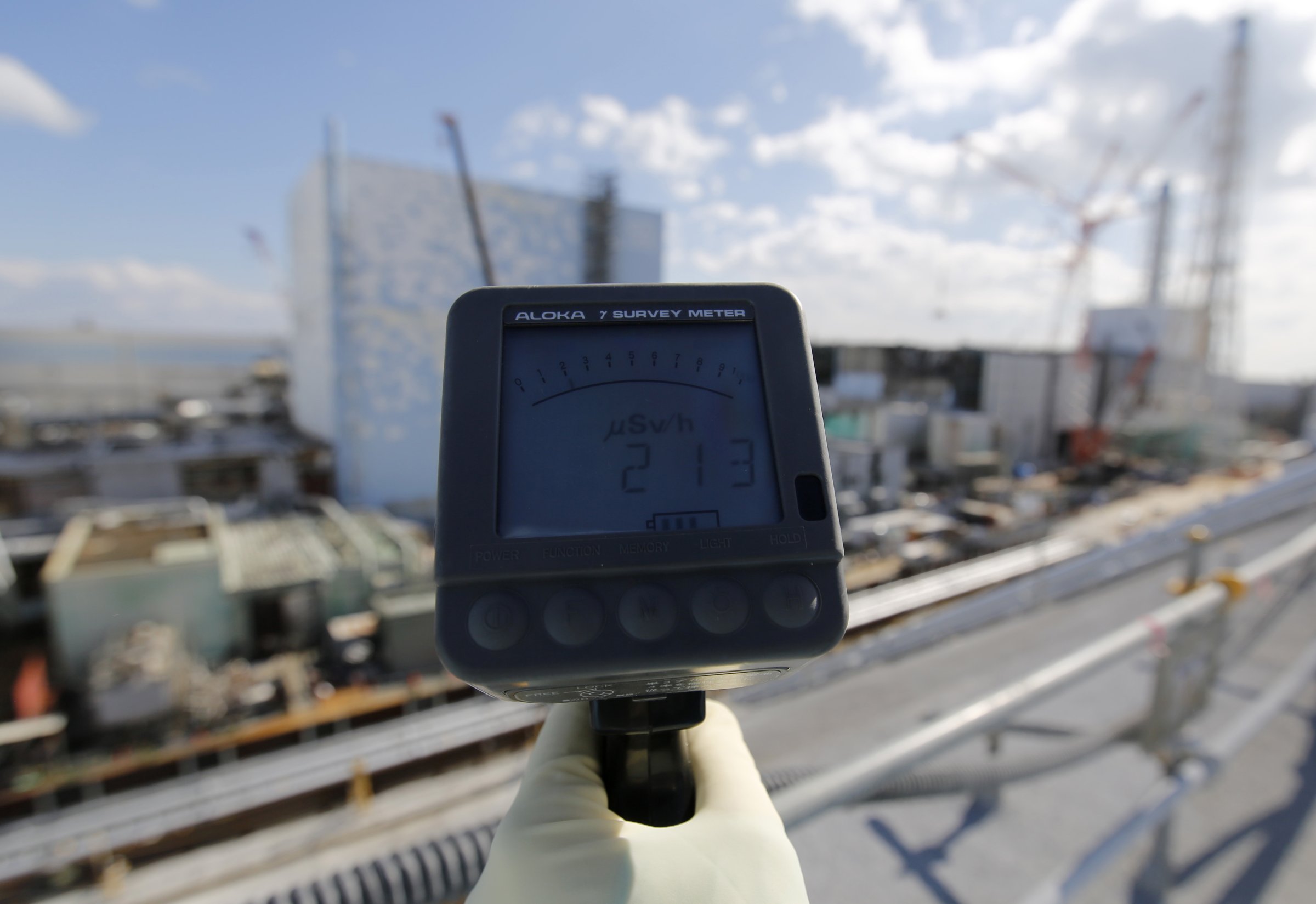

Nearly five years have passed since an earthquake and tsunami in Japan killed 16,000 people and caused nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi plant. New research now suggests that the radiation released by the nuclear disaster may have lingering effects on fish—but that the risk posed to human beings from consumption, thanks in part to strong regulation, is minimal.

The study, published in the journal PNAS, shows that freshwater fish and ocean bottom dwellers near Fukushima have a higher risk of contamination with the radioactive chemical cesium than most other types of ocean fish in the same area. That risk diminishes the further away the fish are from the city’s nuclear facilities.

Read More: The World’s Most Dangerous Room

The study joins previous research showing falling levels of radioactive cesium, which can lead to cancer in humans exposed to it a high rates, in aquatic species overall since the disaster. The research also confirms findings showing ocean bottom dwellers, which are constantly exposed to ocean floor sediment where cesium collects, as particularly vulnerable to lingering radiation. Freshwater fish tend to have higher concentrations of cesium than their oceanic counterparts because of differences in their osmoregulation systems, which controls fluids entering and leave the body.

But overall the study underscores the relatively low risk of people in Japan actually consuming contaminated fish. Regulators in the country adopted one of the world’s most stringent standards on radiation in seafood following the Fukushima disaster, and most freshwater fish consumed in Japan are raised in fish farms that are less vulnerable than uncontrolled environments like lakes and streams.

“There are levels when we should be concerned and there are levels when we don’t have to be concerned,” says Ken Buesseler, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who was not affiliated with the study. “It’s in every fish, everything you eat and drink. It’s all about how much did Fukushima add.”

Fisheries in the most affected regions remain closed. But even if someone were to eat fish with relatively high levels radiation, the chances of consuming enough to cause any serious damage remain extremely low.

Still, researchers say that the Japanese authorities responsible for collecting data on cesium levels should adopt lower detection limits than they currently use that would provide additional insight into the how radiation dissipates after such an accidents. Such information would allow authorities to predict when fisheries can be reopened in a particular region.

“We can answer ‘is it safe to eat?'” says Buesseler. “But not answer when and why will it be safe to eat.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com