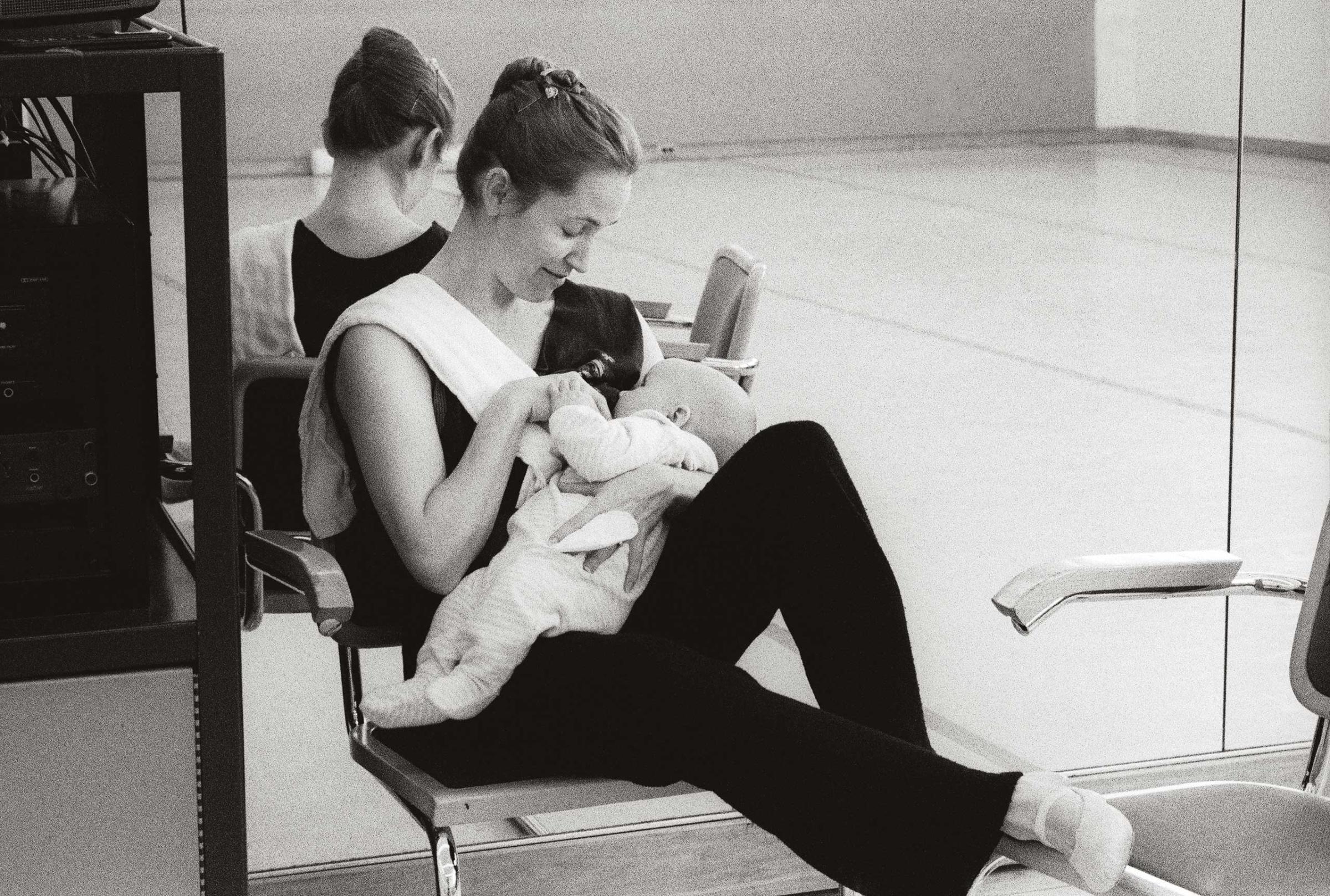

Tina LeBlanc stands at the bar, wearing a black sports bra and an oversized tank top. Her toes are aligned in first position as she arches her back in a graceful port de bras. She is preparing for the upcoming season. Beads of sweat drip down her cheek. Her feet rise into a staccato point as she prepares to leap into the air. Just six weeks ago, she was in labor.

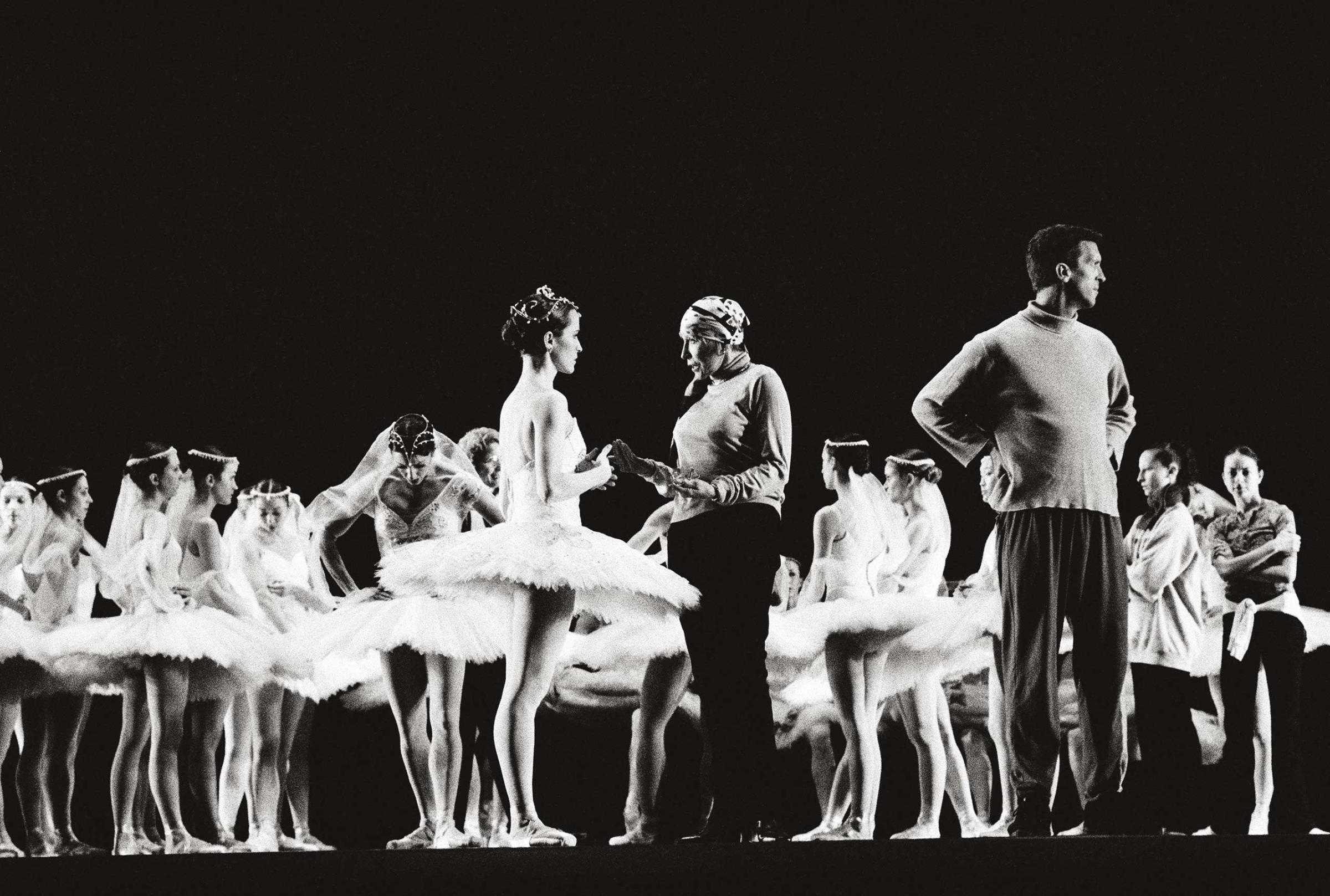

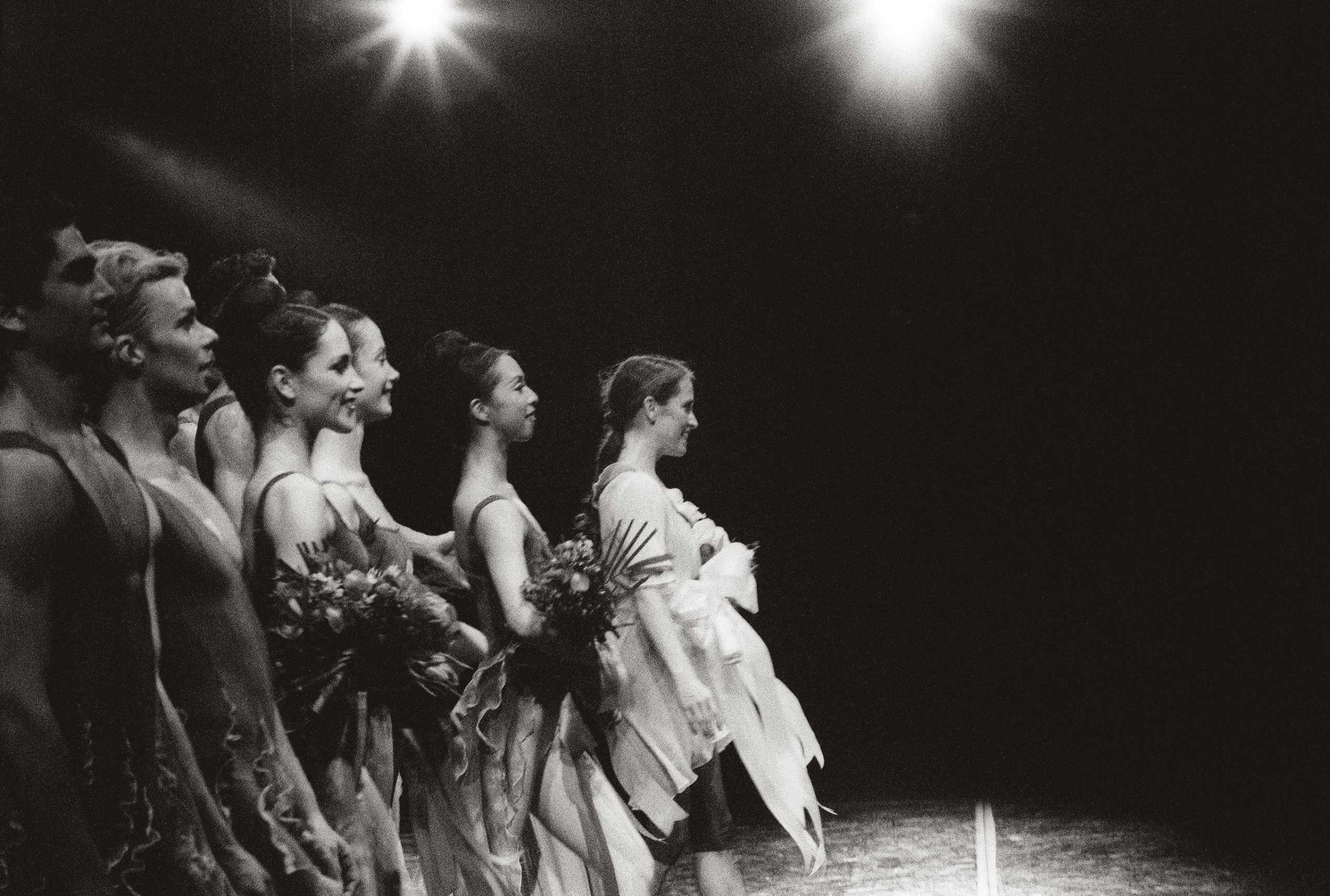

The life of a prima ballerina in one of the U.S.’s best ballet companies is grueling. But for dancers like LeBlanc, the work doesn’t end on stage. Photographer Lucy Gray spent 14 years documenting the lives of three ballerinas—LeBlanc, Kristin Long and Katita Waldo—who had children at the pinnacle of their careers at the San Francisco Ballet. The book, entitled Balancing Acts, provides a window into their pregnancies, marriages, divorces, remarriages—all while dancing on center stage.

Gray draws a comparison between the dancers’ transformation and the distance that refugees cross as they assimilate into a new country. “The distance between that pained woman in the hospital with a baby coming out of her to that sophisticated, elegant, romantic ballerina having an imagined sexual exchange with a man on stage, that, too, is a long reach for a person.”

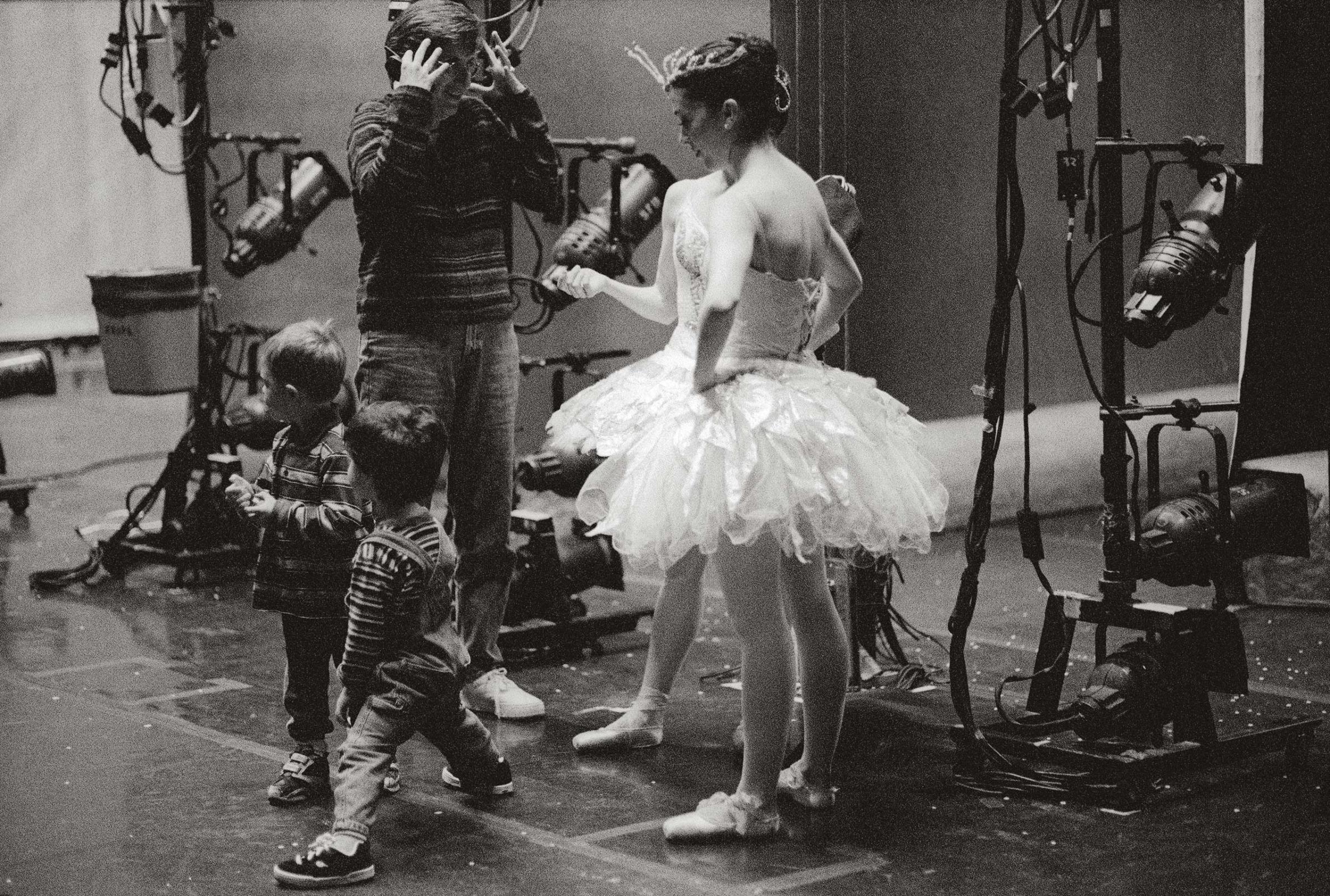

Gray’s black-and-white photographs reveal a kind of brazen authenticity in the highs and lows of work-life balance. One photograph shows a woman pumping milk in her dressing room minutes before going on stage. In another, a dancer leans to the eye level of her toddler in an affectionate goodbye before performing in George Balanchine’s Symphony in C. A woman gives a private lesson just one week before going into labor, while another warms up beside a napping six-month-year-old.

The age-old clichés of the ballet world persist: Many call to mind a stereotypical male-dominated, ironfisted, weight-obsessed world that, beyond the competitive drive, pushes women to self-image insecurities. Gray’s work gives nuance to an often misunderstood arena. “I imagined that they were starving themselves under the lead of some artistic director who was invariably a man, telling them what to do. I didn’t understand the level of choice and power they themselves exert,” she says. “A prima ballerina starts dancing when she is three. By the time she’s 11, she has made the professional choice that she will be a dancer. At 15, she is at a company. These women have a fire in them and from the time they were young, nothing could stop them.”

Beyond the austerity of the finely preened stage performance, they all have their own stories of struggle. Long was a bulimic who was dancing to be thin; Waldo had stage fright; and LeBlanca was ready for a break. For all of them, having a child made them better dancers. “They were dancing for someone else, rather than themselves,” she says. “The added incentive pressured them to take themselves more seriously to provide for their children, as well as freed them up with another outlet. Maybe it’s possible that for the 75 million working mothers in this country, working and having children can make you better at both.”

Gray wants her photographs to provoke questions about how societies cater to childbearing women in the workforce. “This is not about ballerinas,” she says. “This is about women working.”

For those who nearly raise their children on the dance floor, she says that easier access to child care would have been a significant help. “Accept that women have babies,” she says. “It’s what we do, we propagate the species. Whatever they get paid, however important or unimportant the job, 50 percent of the workforce is women, and having that extra help would say, ‘we get who you are, we get what you’re doing and we’re not going to penalize you for it.'”

Gray, who describes herself as a sentient person, says the project came from her own experience. At the age of ten, her father left and her mother began working to support her five children. “I watched her with fear and admiration,” she says. “That sensitized me to the subject of working mothers.”

Lucy Gray is a San Francisco based photographer and writer who specializes in fine art photography.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com