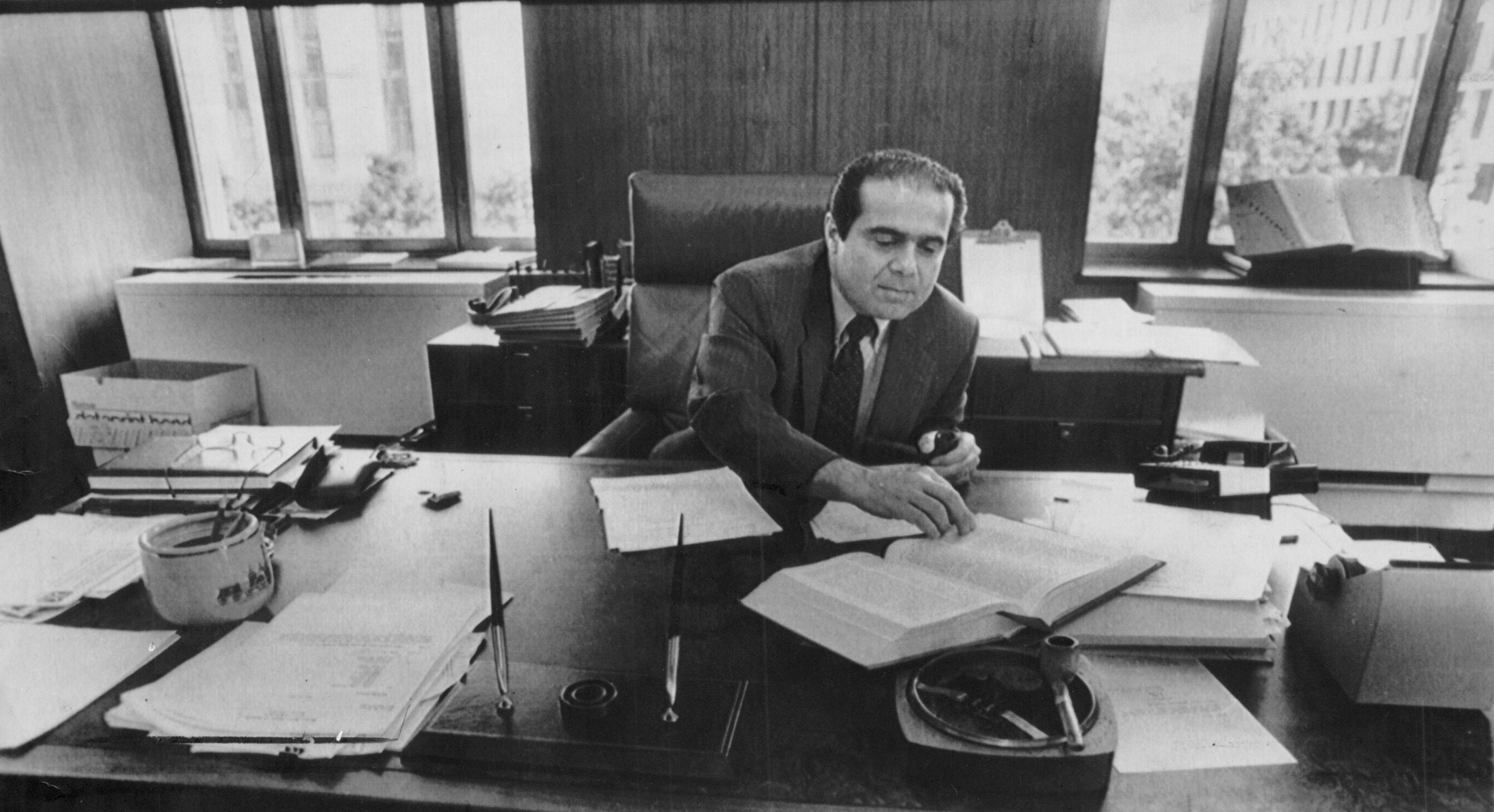

“Reality has overtaken parody,” Antonin Scalia liked to say during his fiery 30-year tenure on America’s highest court. It was a quip typically hurled at judges who diverged from Scalia’s own philosophy, but it also encapsulated his dismay at much of the culture surrounding him. He dismissed the rulings of colleagues as “tutti-frutti opinion” and “argle-bargle.” He scoffed at “homosexual activists.” He deplored “sandal-wearing, scruffy-bearded weirdo[s]” who burned American flags (even as he upheld their right to do so).

“I’m normal,” Scalia once said. “Everyone else is crazy.”

And so it would hardly have surprised the brilliant and irascible jurist that mere hours after he was found dead on a Saturday morning in a quiet quarter of the West Texas mountains, a circus was already unfolding.

The show began within minutes of Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s publicly confirming Scalia’s death, when the communications director for Republican Senator Mike Lee of Utah tweeted, “What is less than zero? The chances of Obama successfully appointing a Supreme Court justice.” Senate minority leader Harry Reid responded that a delay in replacing Scalia would be “a shameful abdication of one of the Senate’s most essential constitutional responsibilities.” Ted Cruz’s Facebook page flooded with comments predicting that Barack Obama would now “attempt to destroy America once and for all” and the like, while the liberal sometime anchor Keith Olbermann pronounced Scalia’s death an “Improvement!”

This was all far off the official script for an institution that—rightly or wrongly, and it is often the latter—thinks of itself as above politics. But many close to the court viewed it with foreboding. “If the depressing deathwatch is the best we can do, I for one would rather go without a Supreme Court,” wrote Stephen Carter, a Yale law professor and author who once clerked on the court. “Seriously.”

It isn’t inevitable that the fight over replacing Scalia will end in gridlock, but it’s close. While Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell insists he has no intention of considering any White House nominee, there are seven Republican Senators up for re-election in states that Obama won at least once. Two of those Senators have already come out in favor of allowing hearings. If Obama selects a candidate with admirers on both sides of the aisle—the White House is reportedly vetting centrist Republican Governor Brian Sandoval of Nevada—moderates and vulnerable Republicans could potentially force McConnell to allow hearings. Fifty-six percent of Americans agree and want the Senate to hold a hearing, according to a recent Pew poll. Whether the seat is filled by Obama or his successor, the stakes have rarely been higher, with the ideological balance, the reputation and in some ways the very authority of the court on trial.

Read: Top 10 Controversial Supreme Court Cases

It is no accident that the nine—now eight, for the foreseeable future—judges who make up the Supreme Court of the United States go to work each day in a building that looks like a temple. It was designed that way, to reflect the court’s exalted role as the branch of government most likely to bend toward justice. And while no court has ever been devoid of politics, the Supreme Court has historically resisted the partisan excesses seen in the neighborhood’s other buildings.

The past three decades, coinciding largely with the Scalia tenure, have put that tendency to the test. It is not only that 5-4 decisions are now often the rule in cases of highest national impact. For the first time in modern history, those splits are now essentially along partisan divides. Justice John Paul Stevens, a Republican appointee who consistently voted with the court’s liberal wing, was the last member of the court to regularly cross lines in cases with political or ideological overtones. A study from William and Mary Law School noted that in the 220 years prior to Stevens’ retirement in 2010, only two decisions designated as “important” (and that had at least two dissenting votes) split along party lines. Over the 2010—12 terms alone, there were five that fit that bill.

In many ways the coming fight over replacing Scalia is a natural extension of his legacy. A bon vivant, sought-after public speaker and unparalleled writer who charmed many an opponent—Justice Elena Kagan, an Obama appointee who had never owned a gun before, became a hunting buddy—Scalia became by far the most famous Justice on the bench. Through his opinions and positions, he helped turn the court into a battleground—a place to fight back against, or fight to preserve, the judicial activism of earlier eras. He was best known for his dissents, for his love of a brawl, for his denouncements. It is this spirit—that interpreting the Constitution is about right and wrong, deception and truth—that will make replacing him so contentious in the coming months. “It’s hard to believe this,” the Justice said in 2012. “I was confirmed by a vote of 98 to nothing. Me!” That could never happen again, and Scalia, who described some fellow judges as “Mullahs of the West,” helped make it so.

“I don’t think in American history there ever has been such a sharp jurisprudential, philosophic, methodological difference between first-rate educated judges who are out of the Republican tradition and those out of the Democratic tradition,” says Laurence Silberman, one of the longest-serving judges on the D.C. Court of Appeals and Scalia’s close friend. “Scalia,” he adds, “was sort of the paradigmatic figure in that.”

Scalia began shaking up the staid, hierarchical Supreme Court from the moment he sat down for his first oral argument in the far-right chair that is reserved for the most junior Justice. As the lawyers presented their cases, he didn’t just ask questions of them–he more or less opened fire. “Do you think he knows that the rest of us are here?” Justice Lewis Powell whispered to Thurgood Marshall, according to John C. Jeffries’ biography of Powell.

With the exception of Clarence Thomas, who has not asked a question from the bench in about 10 years, Scalia’s approach gradually became almost the norm. “He radically changed oral argument,” says Tom Goldstein, a lawyer who argues frequently before the court and co-founded the popular court-watching site Scotusblog. Though the sessions are undeniably more engaging and penetrating than they once were, with eight Justices and at least two lawyers vying for time and talking over one another, they can take on the feel of a crowded presidential debate stage. “Just say ‘bingo’ or something” when you find it, Scalia said to a lawyer who was searching his papers to find the answer to a question. In a 2010 First Amendment case, Justice Samuel Alito, mocking Scalia’s originalism, said to a lawyer, “I think what Justice Scalia wants to know is what James Madison thought about video games.” A few years ago, Kagan cut off a former Solicitor General before he got 10 words out. “We look like Family Feud,” Thomas told a group of Richmond, Va., lawyers, endeavoring to explain his own silence.

Scalia’s biggest legacy by far came from his famed dissents, which he said he wrote for law students. But his singeing language also gave voice to the right on topics from immigration to gay rights. It “boggles the mind,” Scalia wrote in a 2012 case, that the majority wouldn’t let Arizona enforce immigration laws “that the president declines to enforce.” He went on to wonder if any state would have even joined the union if they had known what was coming. Critics noted that his reference to Obama policy was gratuitous, since it wasn’t even part of the case. “The nation is in the midst of a hard-fought presidential election campaign; the outcome is in doubt. Illegal immigration is a campaign issue. It wouldn’t surprise me if Justice Scalia’s opinion were quoted in campaign ads,” Richard Posner, a onetime friend and conservative appeals-court judge who became increasingly critical of Scalia, wrote at the time.

Read: How Scalia’s Faith Reshaped the Supreme Court

In last year’s case upholding Obamacare, just as Ruth Bader Ginsburg did in the 2000 case that handed George W. Bush the presidency, Scalia notably signed off with “I dissent” rather than the more traditional “I respectfully dissent.” A day later, he called the ruling in favor of gay marriage a “judicial Putsch,” adding that he would rather “hide my head in a bag” than join the majority.

Says Goldstein: “If a member of the Supreme Court says its decisions are illegitimate, well, you’ve got to expect the public to listen.”

One casualty of the court’s sharpened philosophical and partisan divides has been consensus building. And while every member of the court owns some responsibility for that, Scalia seemed to have special disdain for compromise. “I prefer not to take part in the assembling of an apparent but specious unanimity,” he wrote in a separate opinion in a 9-0 case striking down a Massachusetts restriction on abortion protesters. When Scalia was nominated, many thought he would, in part because of his charm, forge conservative majorities the way the late William Brennan had cobbled them together on the left. But Scalia soon showed he would rather lose than muddle his opinion. “He didn’t care as much about the result,” says Silberman. “He cared about the reasoning.”

That may be admirable for a judge seeking to shape history. (“I write my dissents for casebooks. There’s no other reason to write them,” Scalia said.) But it is a tough recipe for a court that aims to be a redoubt from the fray in an increasingly frayed democracy. As an institution that exists to resolve problems, a now retired member of the court once said, “there’s a strong obligation to try to bend.” Or as Chief Justice John Roberts put it in his own nomination hearings, “You do have to be open to the considered views of your colleagues.” He added that a priority of any Chief Justice should be to “bring about a greater degree of coherence and consensus.”

Consensus has had its moments in the 11 years since Roberts took his chair at the center of the bench, from the two-thirds of cases that were unanimous in the 2013—14 term to the Roberts-led majority in the Obamacare case that defied party lines (and for which, as TIME’s David Von Drehle put it, he “had to squirm like Houdini to reach middle ground“). It is too early to tell, and may even require undue optimism in this season of vitriol, but perhaps Scalia’s departure will boost Roberts’ efforts.

Regardless of which President chooses the next Justice, or when he or she is sworn in, the remaining members now have a chance to “take back” the court, not merely from the extremes of Scalia’s tongue and pen but also from the broader, uglier partisanship that, having beset the White House and Congress, has been on the verge of taking over the third branch as well. That would mean fewer dissents, more consensus and narrower opinions that take the edge, the partisanship out of the mix to the extent that it is possible. It is an opportunity for the court to get back to what many who revere it want it to be.

—With reporting by TESSA BERENSON/WASHINGTON and JULIA ZORTHIAN/NEW YORK

Felsenthal is the editor of TIME Digital and a former Supreme Court correspondent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com