If you’ve watched the first four episodes of the new season of House of Cards, you know where things stand: President Frank Underwood has been shot and lies in a coma. Now Claire Underwood wants to act as commander-in-chief.

Claire’s seizure of power through her manipulation of Vice President Donald Blythe in Netflix’s new season of the political drama isn’t as outlandish as you might think. In fact, a real First Lady was once in Claire’s position: First Lady Edith Wilson executed affairs of state after her husband, Woodrow Wilson, suffered a massive stroke in 1919. Some scholars even argue she was effectively the first female president. Claire is likely inspired by Edith.

When the stroke rendered Woodrow Wilson paralyzed on his left side and bedridden, Edith and Woodrow’s physician decided to keep the extent of his illness a secret in order to protect her husband’s legacy. At the time, the Constitution did not stipulate what exactly to do if the President were alive but incapacitated.

Edith decided which matters to bring to the President and which to handle herself. She read every piece of paper brought to the Oval Office and became the sole conduit between the president and his cabinet for 17 months. This was in part possible because Vice President Thomas R. Marshall refused to take on the role of Commander-in-Chief. He feared that if Wilson recovered and demanded the Presidency back, the country could erupt in Civil War.

In her autobiography, Edith Wilson called herself a “steward” and denied involvement in matters of state. “I, myself, never made a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs,” she wrote. “The only decision that was mine was what was important and what was not, and the very important decision of when to present matters to my husband.”

But some historians question whether the First Lady downplayed her importance. As the President’s keeper, she became the most powerful person in the White House. Cabinet members have since said Edith met with them in a room adjacent to that of the President and handed down orders, claiming she was relaying Woodrow’s wishes. The cabinet had no choice but to take her word for it. Secretary of State Robert Lansing pushed for the President to be declared disabled, but when Lansing held a cabinet meeting without the president in October of 1919, Edith Wilson said it was an act of disloyalty. Woodrow requested Lansing’s resignation in early 1920.

Statesmen at the time described her as something closer to Secretary of State than First Lady. Newspaper clippings suggest her position of power was an open secret. One newspaper criticized Edith by calling her husband’s later time in the White House a “regency presidency,” while the Daily Mail called Edith a “perfectly capable president.”

As with Claire Underwood, government officials became suspicious of her dealings. Some historians have suggested that Edith Wilson’s decision to hold onto power changed the course of history: if Marshall had taken over for Wilson as President, they argued, he could have negotiated with Henry Cabot Lodge about America’s participation in the League of Nations. Wilson’s dream of creating a unified alliance of countries might have been reached and that that organization could have stemmed the rise of Hitler in Germany. Edith, however, refused to negotiate on the League of Nations plan, saying her husband would not accept a compromise.

So far, Claire can be accused of no such disaster. Her political dealings in past seasons have been mixed, but she certainly has more experience than Edith did. Of course, such a secret would be nearly impossible to carry out nowadays, when politicians’ health reports regularly make news, and the modern media would never allow a First Lady to hide a President’s condition for so long.

But Claire has been smart to choose the Vice President as her puppet. Wilson’s illness motivated Congress to clarify what would happen if the President became incapacitated, closing the loophole that allowed Edith to make decisions. Congress ratified the 25th amendment to the Constitution—which says that the Vice President will be sworn in as acting president if the president is impeached, incapacitated or killed—in 1967. Any first lady who would want to seize control in her husband’s absence would have to do so through the Vice President, as Claire Underwood has.

It’s a new take on an old TV trope. Almost every fictional depiction of the White House has included a successful or attempted assassination, from The West Wing to Scandal and 24. Though the plot amps up the drama, it’s true to life: Almost every president has received death threats. Here are the unlucky real commanders-in-chief who were the victims of a shooting:

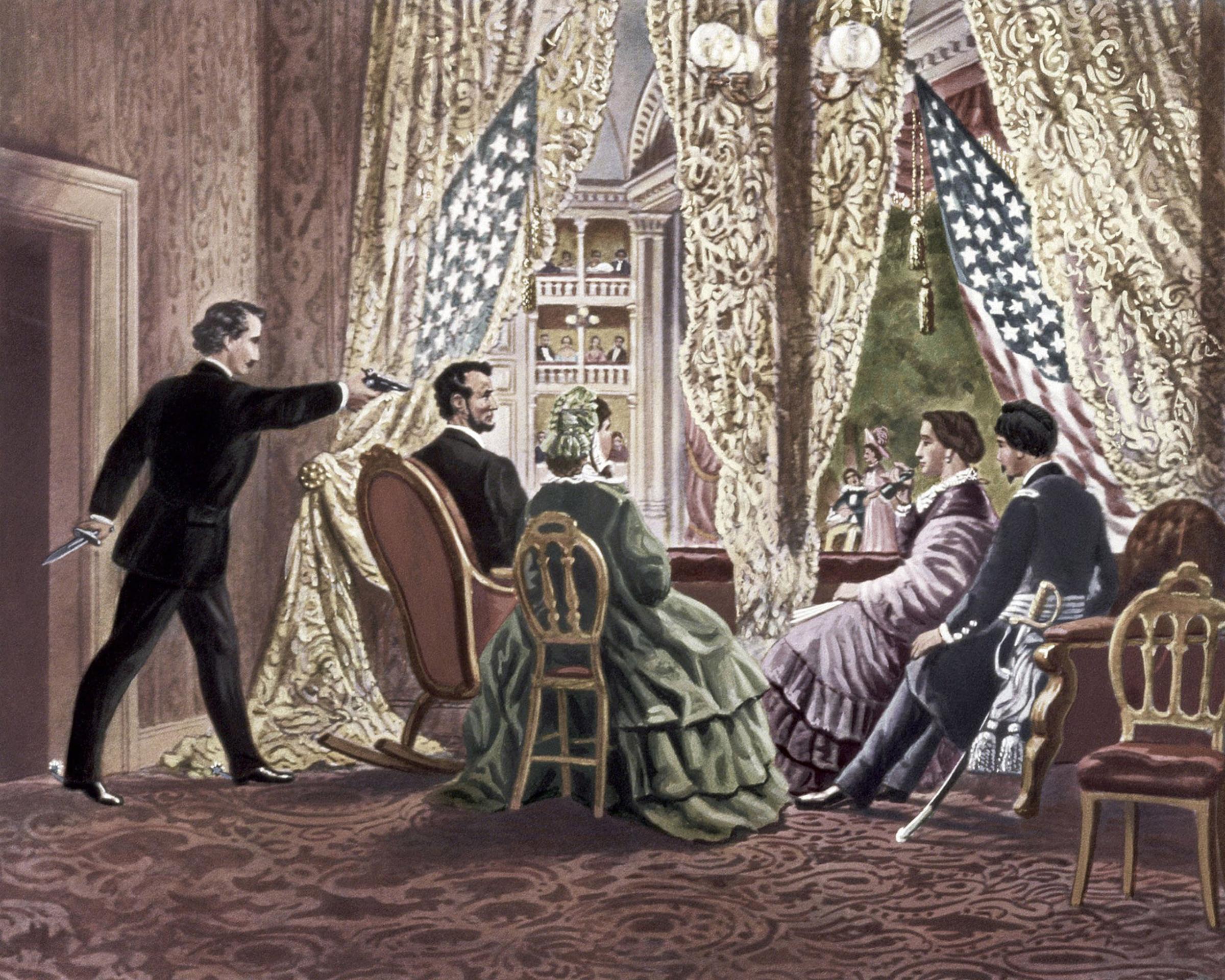

Abraham Lincoln

Date: April 15, 1865.

Shooter: John Wilkes Booth.

Result: Lincoln was killed, and Andrew Johnson became President, changing the course of post-Civil War history.

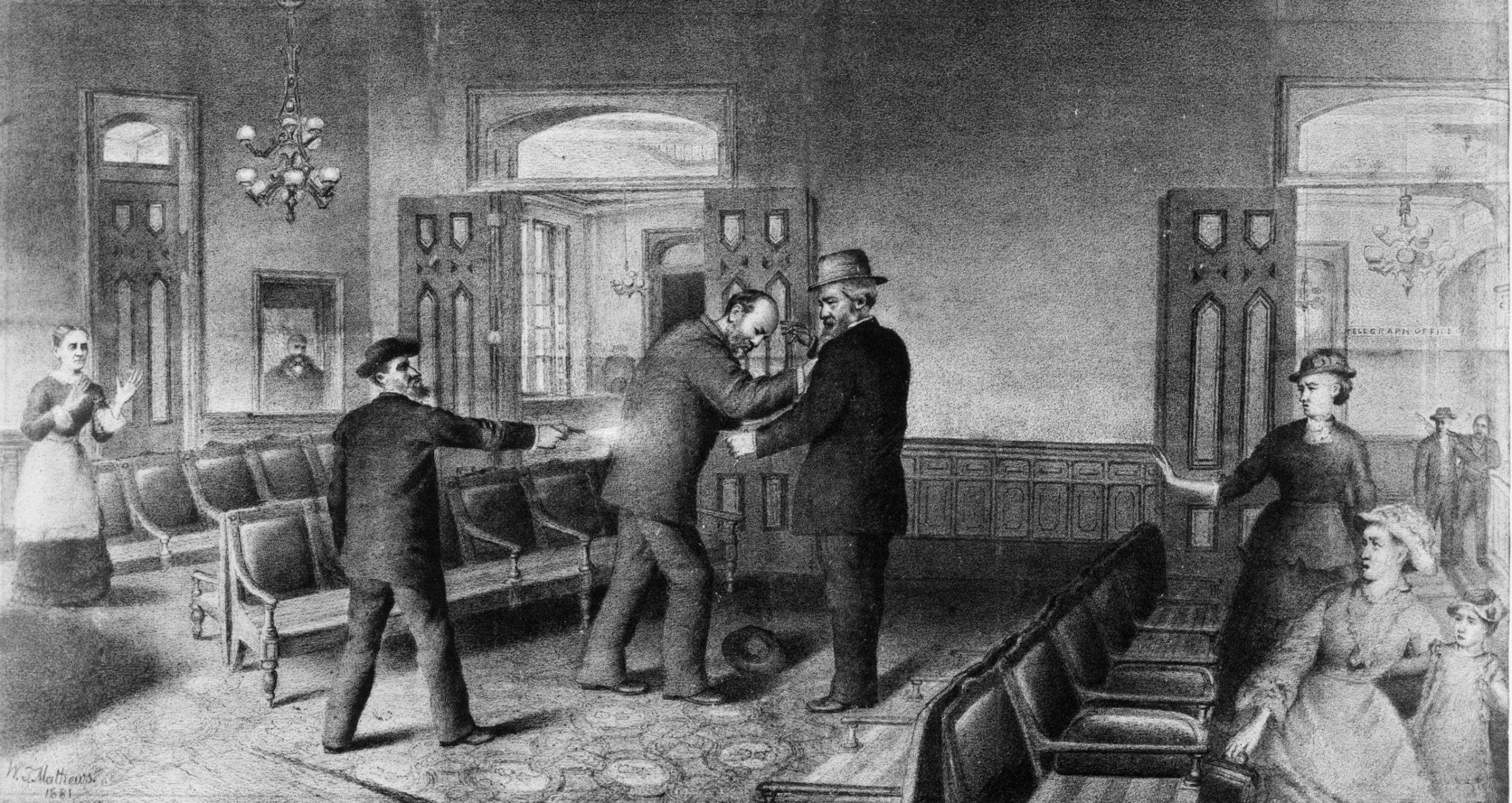

James A. Garfield

Date: July 2, 1881.

Shooter: Charles Julius Guiteau.

Result: Garfield died of his injuries on Sept. 19 of that year.

William McKinley

Date: Sept. 6, 1901.

Shooter: Leon Czolgosz.

Result: McKinley died from his wounds eight days later.

Theodore Roosevelt

Date: Oct. 14, 1912.

Shooter: John F. Schrank.

Result: The assassination attempt failed, and Roosevelt was still strong enough to deliver a speech almost immediately after being shot.

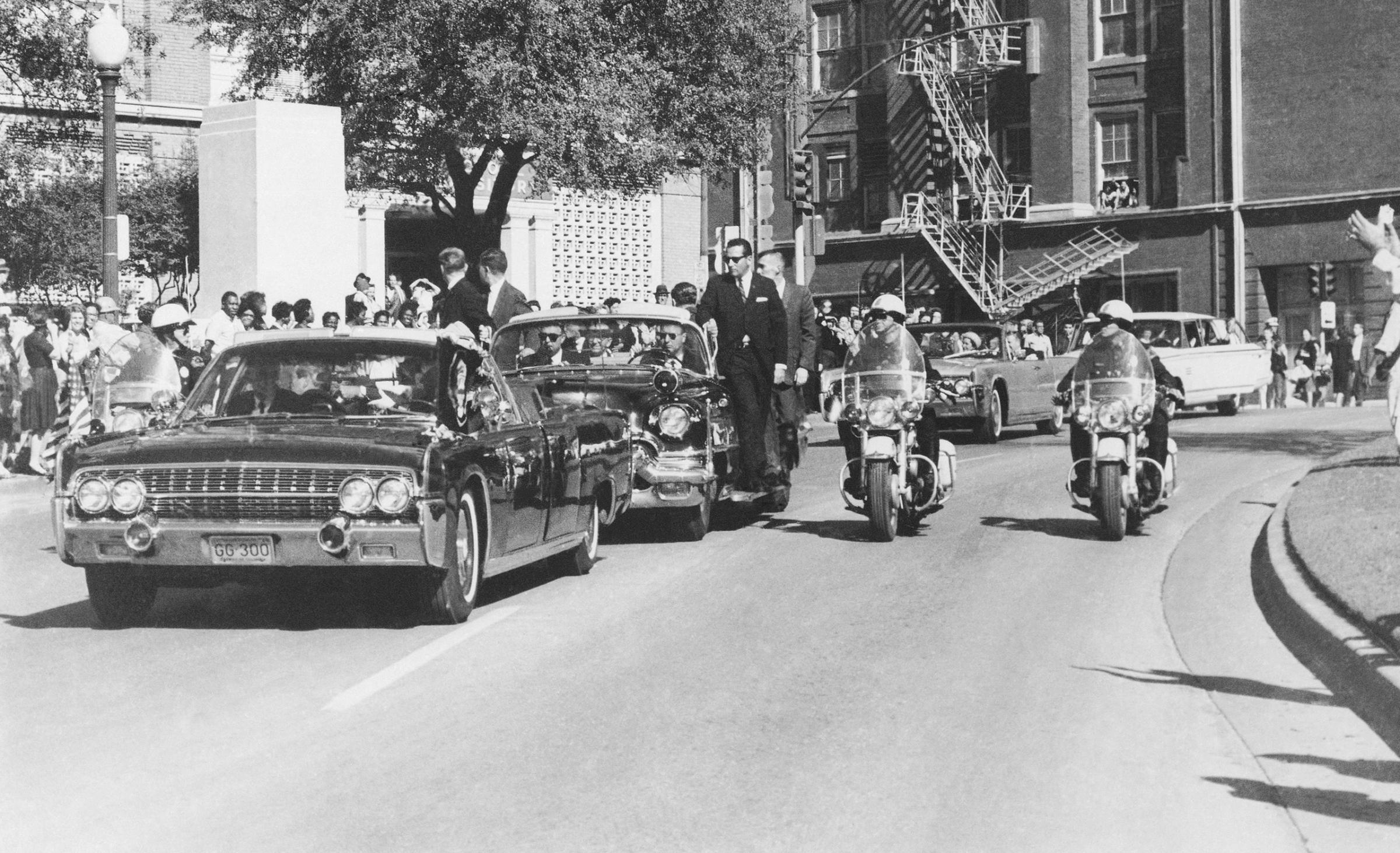

John F. Kennedy

Date: Nov. 22, 1963.

Shooter: Lee Harvey Oswald.

Result: Kennedy was killed, in one of the 20th century’s defining events.

Ronald Reagan

Date: Mar. 30, 1981.

Shooter: John Hinckley, Jr.

Result: Reagan was wounded but recovered.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com