Here’s the thing, and it is not a small thing: Harper Lee was a smart, funny, happy woman. She used to like to play golf, spend time with friends in Monroeville, entertain visitors in New York City. To her friends and family, she was always Nelle.

She was not the first famous Lee from the South, of course, and it is fascinating that she was in fact related to Robert E. Lee. Harper Lee was born on April 28, 1926, in Monroeville, Alabama, to Amasa Coleman Lee and Frances Cunningham Finch Lee. Her father, a lawyer and the model for Atticus Finch in the novel, had been born in Butler Country in 1880 and after he married Frances, the couple moved to Monroeville in 1912. There he was a supremely respected man and, in fact, served in the Alabama state legislature for a dozen years, from 1927 to 1939. As said earlier, he once defended two black men accused of killing a white storekeeper; both men were eventually convicted and hanged. Clearly this family remembrance made an impression on young Nelle.

But to emphasize: Hers was a mostly comfortable and congenial upbringing, far less strange than that of Scout Finch, not to mention that of Boo Radley.

Named, sort of, after one of her grandmothers (“Nelle” is “Ellen” backwards), she was the family’s youngest child and finally would survive brother Edwin (who died in 1951), sister Louise (who died in 2009) and sister Alice, who became a lawyer, took over their father’s practice and died in 2014.

Nelle would never marry, but she always had a passel of friends and admirers. In 1944 and ’45, she attended Huntingdon College in Montgomery, Alabama, and then switched to the University of Alabama, where she explored her burgeoning interest in writing (nurtured in high school) and her father’s interest in law. She would spend time as an exchange student at Oxford in England, and would spend other time contributing to Bama’s humor magazine Rammer-Jammer. She would, by 1949, land in New York City. There is nothing unusual about this smart young woman’s profile. Her arc was that of an achiever.

She had a particular pal in her youth, and this fact will always fascinate. The boy named Truman Streckfus Persons had moved to Monroeville in 1928 to live with his aunts, whose house was right over the stone wall from the Lees’ property. Nelle and Truman became close friends; much later, she would become commemorated as a character in his novel Other Voices, Other Rooms, and he, now named Truman Capote, would be, as already noted, immortalized as Dill in Mockingbird. They stayed in touch after moving on from Monroeville. Both continued to write—to each other, and then for millions of others.

In New York, Lee worked as a reservation clerk for Eastern Air Lines and British Overseas Airways. During the 1950s, she worked on Go Set a Watchman, which could not find a publisher. She then went to work on To Kill a Mockingbird, and in 1957 signed a deal and embarked upon a two-year process of rewriting and refining.

Affairs get interesting here. On November 16, 1959, The New York Times ran a brief account of a crime in Kansas—“a wealthy wheat farmer, his wife and their two young children were found shot to death today in their home . . .”—that caught the attention of Capote. He determined to go to the Midwest and investigate; the fruits of his labors would be his ground-breaking 1966 book, In Cold Blood. As he set out on his grand enterprise, he realized that no one was better suited to help him interview the heartland natives than his empathetic-to-the-core friend from Monroeville, Nelle. And so, even on the verge of her own triumph in literature, she was recruited and went to Kansas with Capote. He would later tell George Plimpton for a New York Times Book Review piece that Lee was always, and in this instance certainly proved herself to be in spades, “a gifted woman, courageous, and with a warmth that instantly kindles most people, how- ever suspicious or dour.”

Because—until the publication of Watchman in 2015—Harper Lee had allowed her reputation to rest on one book alone, there had always been suspicion that the book was something other than a miracle. Because, also, Truman Capote was her devoted friend, there has always been a theory out there that he had something to do with the writing of Mockingbird. Such notions are nonsense, and the words of Capote himself—“I liked it [To Kill a Mockingbird] very much. She has real talent.”—say as much. Capote, of all people, would never have had any problem at all taking credit where credit was due, and he never really took any credit for his friend’s masterwork. So, in the Lee biography, there will always be that fascinating Capote interlude. (And what town can claim more scribbling geniuses per capita than Monroeville, Alabama?)

But to return to the biographical sketch: Lee wrote her novel. It quickly became the phenomenon it remains. And then she wrote no more.

Well, not quite true. In the early 1960s, with her first blush of fame still rosy, she wrote a couple of homey articles for McCall’s magazine and Vogue.

And then she pretty much stopped writing for the public, as the awards—the Pulitzer (first woman recipient for literature since 1942); the Brotherhood Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews; scores of others—and royalty checks regularly arrived in the mail. In its first two decades, the novel would be translated globally and would sell millions of copies. By now, it has sold more than 40 million.

Nelle Harper Lee’s world was one thing before 1960, then—especially after the film— it was something other. But she kept it as relatively the same, and as sane, as she could.

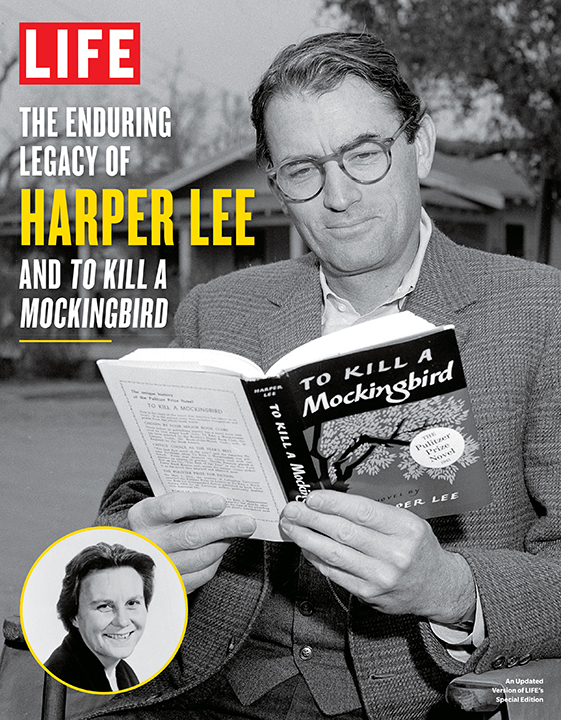

Read more in LIFE’s new special edition, The Enduring Legacy of Harper Lee and To Kill a Mockingbird, available on Amazon.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com