One of the first orders President Obama signed following his inauguration in 2009 was one requiring that the prison housing suspected terrorists at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, be closed within a year. On Tuesday, after more than seven years in office and in response to a congressional mandate, he forwarded his last-ditch proposal to do that to Capitol Hill.

“For many years, it’s been clear that the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay does not enhance our national security—it undermines it,” Obama said at the White House, minutes after the Pentagon-drafted proposal was delivered to Congress. “It’s counter-productive to our fight against terrorists because they use it as propaganda in their efforts to recruit,” he said, flanked by Vice President Joe Biden and Ashton Carter, the Secretary of Defense.

But the 21-page proposal would require a change in the law barring the detainees from being housed on U.S. soil, and Congress has shown little evidence it will relax that ban. If the Republican majorities in Congress refuse to budge, it looks like Obama will leave office 11 months from now having failed to make good on one of his major campaign pledges.

Congressional reaction to Obama’s proposal generally split along partisan lines. “President Obama’s plan makes it clear that there are safer, more cost-effective, and more humane alternatives to this ongoing violation of human rights,” said Jackie Speier, D-Calif., a member of the armed services committee. “It is time for us to bring this issue to a vote and end this dark chapter of our history.”

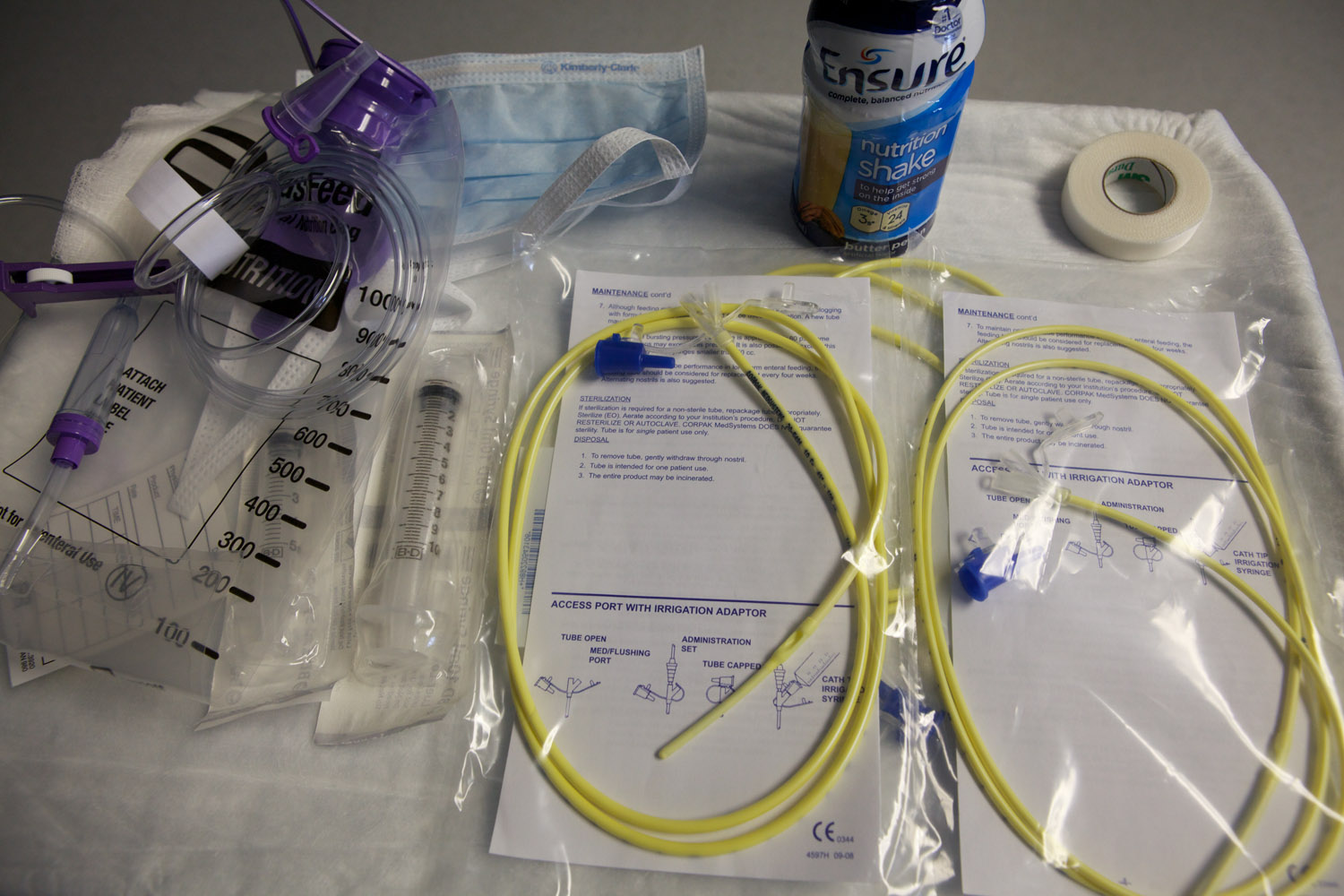

Inside Guantánamo Bay: Photographs by Eugene Richards

GOP reaction was sure and swift: no way. Rep. Michael McCaul, R-Texas, said U.S. citizens “do not want our communities to become terrorist targets.” The chairman of the homeland security committee criticized Obama for wanting to give alleged terrorists “a one-way ticket to America.”

“Instead of trying to empty out Gitmo and moving dozens of dangerous terrorists to South Carolina, Kansas or Colorado, the President needs to put our national security interests first,” said Senator Tim Scott, R-S.C. “There is simply no reason to put a target on an American community, when we already have an isolated facility, well-guarded by Marines that is more than capable of holding them.”

Even groups like Amnesty International opposed the plan. “The proposal to move some of the detainees to the U.S. mainland for continued detention without charge is reckless and ill-advised,” Naureen Shah, director of the group’s Security and Human Rights Program, said in a statement. “The possibility of a new, parallel system of lifelong incarceration inside the United States without charge would set a dangerous precedent.”

Obama proposes spending up to $475 million to detain up to 60 Gitmo detainees at an unspecified prison in the U.S. Some of them would face a military trial, while others could be kept locked up indefinitely.

The Administration has said it has looked at 13 sites, including building a new facility at one of six U.S. military bases. But the cost of that beefed-up security could be eclipsed in less than three years due to annual savings as high as $180 million reaped by shuttering Gitmo. The U.S. is spending $4.4 million annually for each of the 91 detainees, who are guarded, cared for and prosecuted by a 2,000-strong Pentagon force (roughly 35 of them are slated to be transferred to other nations by this summer; Gitmo’s peak prison population was 680 in 2003). Last year, the Pentagon looked at possible sites in the U.S., including the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kan.; the Consolidated Naval Brig, in Charleston, S.C.,; the Federal Correctional Complex’s “supermax” prison in Florence, Colo.

A senior Administration official said Tuesday that the government is confident it can keep the American public safe if the detainees are moved to a U.S. facility. “The politics of this are tough,” Obama said, referring to the “scary” prospect of housing those linked to 9/11 and other terror attacks on American soil.

A 2012 review of possible U.S.-based Pentagon facilities where the detainees could be held said that they were only 48% full, but added that such a move would bring the alleged terrorists closer to American citizens. The Pentagon’s “current ability to minimize risks to the public is attributable to Guantánamo Bay’s remote location and limited access, whereas DOD corrections facilities in the United States are generally located on active military installations in close proximity to the general public,” the Government Accountability Office report said.

“Additionally, DOD officials indicated that locating detention operations on an active military installation could present risk to the installation’s core operations such as administrative and training operations,” the GAO added. Non-military federal prisons were operating at 138% of capacity. “Holding Guantánamo Bay detainees could require triple bunking of inmates or expansion of facility capacity in order to maintain security for personnel, inmates, and detainees,” the GAO said. A senior Administration official said Tuesday that even if the detainees were moved to a non-military prison, they would be guarded by U.S. troops, not civilians.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com