Teachers’ unions may have just gotten a reprieve. The U.S. Supreme Court was widely expected to hit them hard in June by cutting off their primary source of funding: compulsory union dues.

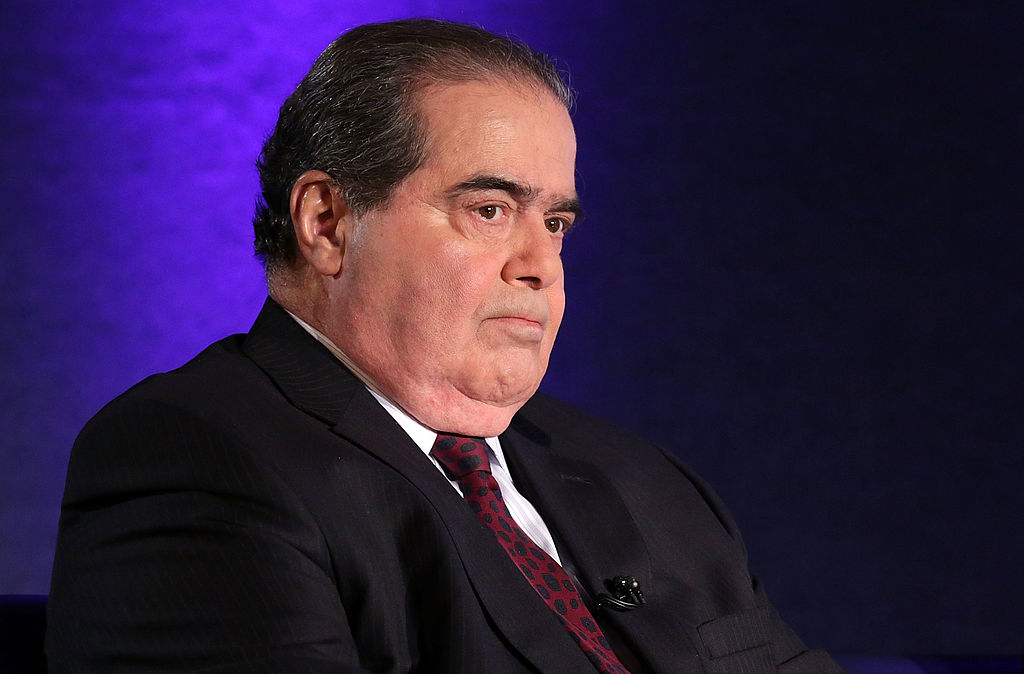

In Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, a narrow majority of Supreme Court justices was expected to decide that collecting such dues violate the First Amendment. Justice Antonin Scalia, who hinted strongly during oral arguments in January that he considered mandatory dues unconstitutional, would likely have been a deciding vote.

His unexpected death, at 79, on Saturday throws that decision into question. It also potentially reverses what would have happened to teachers unions, and other public sector unions, had he lived.

Here’s how. A decision against the unions in the Friedrichs case would have eviscerated the funding model for California teachers’ unions, which primarily rely on mandatory dues. It also would have cast a giant, Constitution-sized shadow of doubt over almost all public sector unions across the country, which overwhelmingly rely on levying mandatory dues. That because the Friedrichs decision almost definitely would have resulted in overturning a four decade-old ruling in another Supreme Court case called Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, a foundational text for unions.

Abood allows public sector employees to collect compulsory or “fair share” dues for the purpose of collective bargaining. Without Abood, union lawyers would be vulnerable to suits challenging any kind of mandatory dues.

The idea of putting union lawyers on the defensive is, of course, is a dreamscape for Republicans, who have long sought to make the entire country a so-called “right-to-work” jurisdiction, where no employee can be required to pay mandatory union dues.

Part of that’s political. In “right-to-work” states, such as Wisconsin and Mississippi, unions are generally smaller, weaker and hold much less political clout. So a decision to overturn Abood would be a gut punch to Democrats, who rely on the unions as a primary source of political support. The weaker the unions are, the weaker their political support.

While we don’t know for sure how any of the justices would have ruled in the Friedrichs case, Scalia had telegraphed that he considered compulsory union dues an affront to the freedom of speech, which includes acts of political expression, like spending money. The Friedrichs decision was always widely expected to break down on ideological lines, with the five conservative justices lining up with Scalia, and the four liberal justices ruling to uphold Abood.

With Scalia’s death, the Friedrich case will likely end with a 4-4 tie. Under that scenario, the high court would defer to the ruling of the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which originally decided in favor of the teachers union. If that’s what ends up happening, California’s law, which currently allows compulsory union fees, would stand, as would Abood. Other challenges to public sector unions’ ability to collect mandatory fees would be weaker.

Labor leaders foresaw the expected Friedrichs decision as essentially a death knell. After all, if all teachers or other workers who benefit from a union’s collective bargaining—higher wages, better health care, etc.—can’t be made to pay compulsory dues, then it creates a free-rider problem and pulls the rug out from underneath the union fundraising model.

Those who oppose powerful teachers unions, including the conservative Center for Individual Rights, which is arguing the Friedrichs lawsuit, and self-proclaimed “pro-student” groups, such as The Seventy Four, had celebrated the expected outcome of the case. They generally see compulsory fees as a violation of basic freedoms: why should teachers be forced to pay dues to an organization with whom they disagree?

In the Friedrichs case, Rebecca Friedrichs, an elementary school teacher, and nine other non-union teachers in California, argued that mandatory fees amounted to coercing them into support union bargaining positions they didn’t agree with.

Joshua Pechthalt, the president of the California Federation of Teachers, said in a statement Sunday that Scalia’s death would likely “result in a delay” in the Friedrichs case, but he stopped short of declaring victory. “I think the public sector unions and the education unions have to continue the organizing we have been doing with the assumption nothing has changed,” he said.

Those who would like to unwind the power of teachers unions may not win in Friedrichs case, but there’s no reason to believe they won’t bring similar cases in the future, Pechthalt warned. Whoever is appointed to fill Scalia’s seat “could be interpreting the Constitution for the next generation.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com