A lethal conflict is underway in the predominantly Kurdish towns of southeastern Turkey, with Turkish security forces on the offensive against local Kurdish militants.

The recent crisis is the result of a breakdown in negotiations between Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a militant organization that has fought the Turkish government since the 1980s. Combined with spillover from the war in neighboring Syria, the renewed political violence has propelled southeastern Turkey to the brink of conflict not seen since the zenith of the war between the Turkish security forces and the PKK in the 1990s. And residents of the area fear it will only get worse.

Read More: How Bashar Assad Is Trying to Win the Peace in Syria

Inspired in part by the success of Kurdish armed groups who managed to carve out autonomous Kurdish zones in Syria, some Kurdish youths have erected barricades, declaring neighborhoods as autonomous zones in recent months. In response, the government placed has whole neighborhoods and villages under curfew for weeks or months at a time while the security forces battled the militants. According to Turkey’s Human Rights Association, at least 407 people were killed in violence in the first nine months of 2015, the majority of those deaths taking place from July onward. During a nine-day curfew in the town of Cizre in September, 22 people were killed, 16 of them shot dead, according to human rights groups, but the Turkish government has refused to acknowledge any civilian casualties.

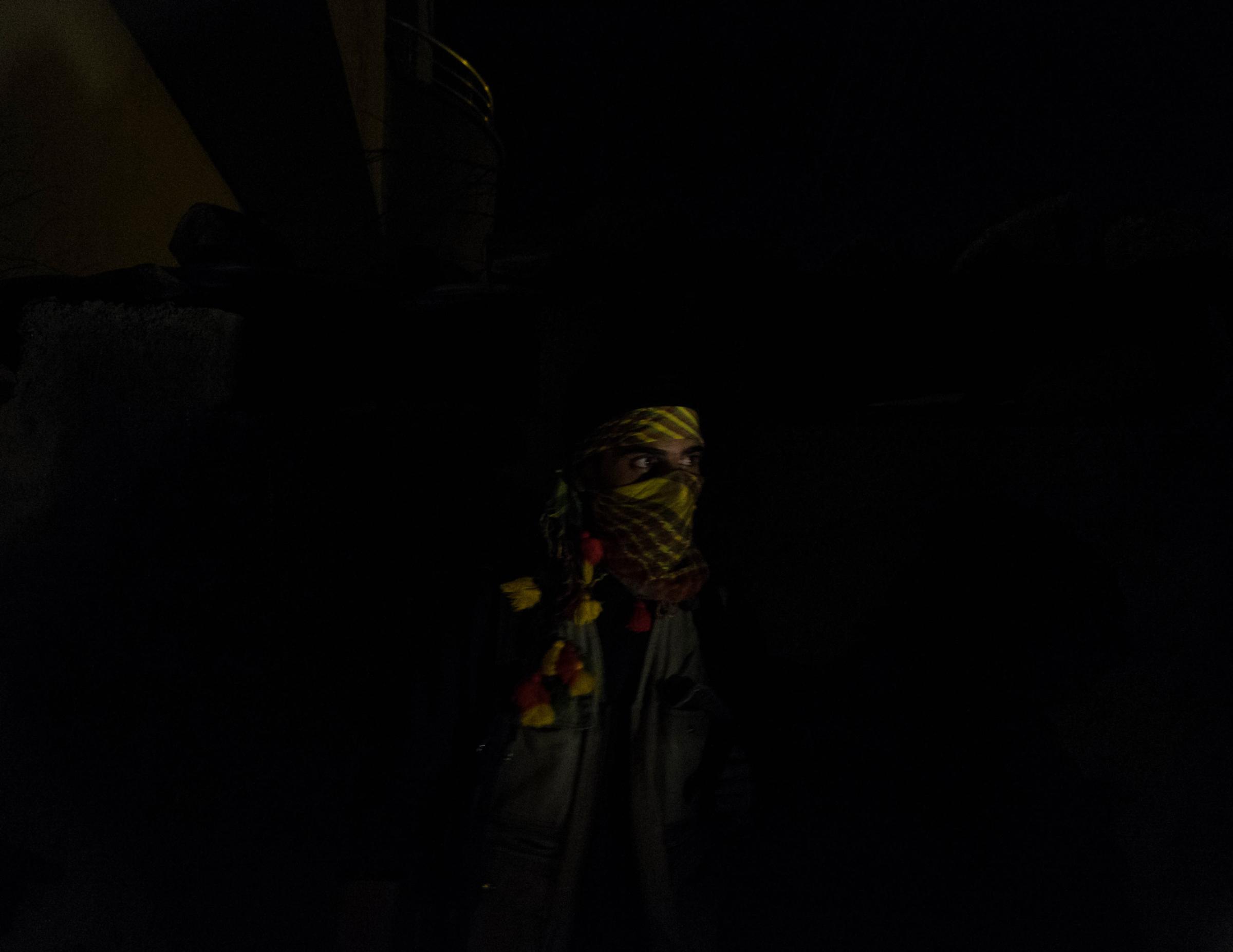

Tommaso Protti, a Sao Paulo-based photographer, gained unique access to some of the self-declared “autonomous” neighborhoods in southeastern Turkey during a visit to the area in 2015. His photographs depict a tense situation, with young men carrying rifles, standing guard at night against the Turkish security forces. Protti managed to speak with the young men who joined local militias known as the YDG-H (Patriotic Revolutionary Youth Movement). One of the main questions about these groups is how closely they are linked to the PKK and its imprisoned leader, Abdullah Ocalan.

“They always answer, yeah of course we support PKK ideology,'” says Protti. “We are really close to them, but we are not controlled by them.

“All these people grew up with this ideology, grew up with the background of repression, relatives who have been in PKK, or who have been killed during the 90s, or who have been arrested. It’s a kind of endless conflict and confrontation between PKK and the state.”

Human rights groups have condemned what they describe as abusive policies by the security forces. Amnesty International says the security operation in the southeast amounts to “collective punishment” of the majority Kurdish communities in the region.

The most recent cycle of violence began when a suicide bomber killed at least 33 people in the border town of Suruc in July 2015. The targets were mainly student activists on their way to rebuild the Kurdish town of Kobane, in Syria, which withstood a siege by the ISIS the previous year. The Suruc bombing was blamed on ISIS.

Read More: Meet the Last American in Damascus

Two days later, members of the PKK killed two Turkish police officers in nearby Celanpinar, who they claimed were collaborating with ISIS, in revenge for the killings in Suruc. Later in July, the Turkish government responded by launching airstrikes on ISIS positions in Syria and PKK camps in northern Iraq. The killings and airstrikes dimmed any remaining hopes for reviving peace talks between the government and PKK.

The violence spiked again in October with a dual suicide bombing at a peace rally in Ankara. That attack killed more than 100 people, the worst suicide bombing in Turkey’s recent history. The primary targets again were members of the domestic political opposition, including the pro-Kurdish HDP. Around the same time, the youth militias cropped up in the southeast, taking advantage of public anger and seizing control of neighborhoods. After months of clashes with the security forces, some of the neighborhoods declared autonomous by the militants have been devastated.

“It’s not just like in one place with sporadic clashes. This is a concerted situation in lots of towns in the southeast,” said Emma Sinclair-Webb, a senior Turkey researcher at Human Rights Watch in an interview with TIME in November. “This was a kind of cycle of spiraling violence and the government was happy to incite it,” she said. “Of course the PKK were a very willing partner in this.”

One of those neighborhoods is the Sur district of the city of Diyarbakir, the regional seat of Kurdish southeastern Turkey. In an interview with TIME in November, a resident of the neighborhood, Mehmet Karakus, 70, said he had witnessed some of the fighting. Several weeks before he had helped carry a man with a head wound to safety after group of unarmed protesters brought the unconscious bleeding victim to his door. “If 1o people come together and exercise their democratic rights, to protest or shout slogans, suddenly the cops come and attack people,” he said. “Personally, I think there’s going to be an urban war.”

With PKK-linked Kurdish militias expanding their territory across the border in Syria, many expect the violence inside Turkey to escalate even further. The Turkish has already begun shelling Kurdish positions in Syria. Following yet another bombing in Ankara in February, the government again blamed a Kurdish group. For the beleaguered people of southeastern Turkey, all signs suggest the worst still to come.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com