Standing in the penthouse apartment of his presidential library in Little Rock, Bill Clinton reached into a bookcase and pulled down a green first-edition from 1919: Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to his Children. Gently cradling the relic, he wrote inside: “From another fan of Theodore Roosevelt,” and signed it.

Then he handed it to my 13-year-old son Tyler.

Tyler is autistic. He is on the high-functioning end of the spectrum, diagnosed at age 12 with Asperger’s syndrome. Tyler is a uniquely wired child: lacking social graces but blessed with an outsized intellect, a warm heart, and other supreme qualities often overshadowed by his quirkiness.

But this story isn’t about Tyler. It’s about what Presidents Clinton and George W. Bush did for him—and what their small acts of kindness says about the hidden humanity of our political leaders.

The day Tyler was diagnosed with autism, Lori made me promise that I would spend more time with him. My ego-stroking career covering the White House and presidential campaigns had kept me away from Tyler and his two sisters. One of Tyler’s obsessions is U.S. history, so it was Lori’s idea to send us to the homes and libraries of past presidents—Washington, Adams, Roosevelt, Kennedy and Ford, for starters.

Lori told me to take notes on our travels. I called them “guilt trips.” She told me to write a magazine article about them, then a book, so that Tyler would forever remember how much we loved him.

Lori even urged me to try to arrange visits with Bush, Clinton, and their successor, President Barack Obama. I thought she was joking: That’ll never happen. But she was dead serious, telling me such visits would help him grow socially. “You can use a job that took you away from Tyler to help him now.”

So it was that Tyler spent 45 minutes talking to Clinton before hugging the first-edition Roosevelt to his chest. Eight days after that, we visited Bush in Dallas.

Each man showed me how to be a better father to Tyler.

With Clinton, it was almost by accident. I noticed how the ex-president dominated the conversation, shifting from one obsession to another: coral reefs, terrorism, national security, the joys of being a governor, the perils of new media, and the broken business models of book publishers. It was brilliant, fascinating stuff for a journalist like me. It was a tad boring for Tyler.

Clinton didn’t seem to notice or care, which struck me as odd because I knew better. I knew that Clinton is wired to connect with people—larges masses of people, anyhow.

Suddenly, I saw Tyler in another light. If the man who made empathy his calling card (“I feel your pain”) can miss obvious social cues, why worry so much about my Aspie son? There is no perfect social animal—not even Bill Clinton! Maybe the autism spectrum is broader than we care to admit, and we’re all on it?

With Bush, it was different. The former president greeted us from behind his neat desk. He was tilted back in his chair with his feet propped on the desktop and a coffee cup marked POTUS in his hands. Something about the Texan immediately put Tyler at ease.

Bush got right down to business.

“Going to school?”

“Yes,” Tyler replied.

“Do you like school?”

“Pretty good.”

“Favorite subject?”

“American studies.”

Bush’s conversational style brought to mind a field of Texas oil drills, each one probing, probing, probing, methodically and relentlessly, until hitting pay dirt. “Do you have any idea what you’d like to be when you get older?”

“Maybe a comedian.”

This was the first I’d heard of Tyler’s ambition. I had tried to get him to open up, but he never would. I knew what I wanted him to be—a ballplayer—and because of his diagnosis and these guilt trips, I was coming to terms with the fact that my dreams weren’t his. But this was new. This was important. This was amazing.

I won’t go into the full conversation here, but sum it up to say that while Clinton famously felt the nation’s pain, Bush felt Tyler’s.

These meetings got me wondering: Would we think better of our political leaders if we saw them in settings likes this? Should journalists like me do more to show the human side of presidents? Should handlers do less to protect presidents from unguarded moments? I think the answer is yes.

Abraham Lincoln’s grief. Teddy Roosevelt’s advice to his kids. The resentment John Kennedy and Gerald Ford felt toward their fathers. Harry Truman’s fierce devotion to his daughter. How much was known about their lives during their lifetimes?

Time eventually lifts the veil, but only in service of historians. In real time, while they’re still serving, shouldn’t we know more about our presidents as people?

I’m not sure why Clinton and Bush agreed to meet Tyler. While I respect both men, I never spared my criticism during their presidencies, and in 2012, retired from elected office, neither Clinton nor Bush expected their favors returned.

I chalk it up to something you don’t hear much about in politics: decency. Like most politicians, the former presidents are public servants at their core. Far from perfect (as reporters like me never fail to point out), most men and women who enter politics are fundamentally good people in a bad system. But that’s a story for another book.

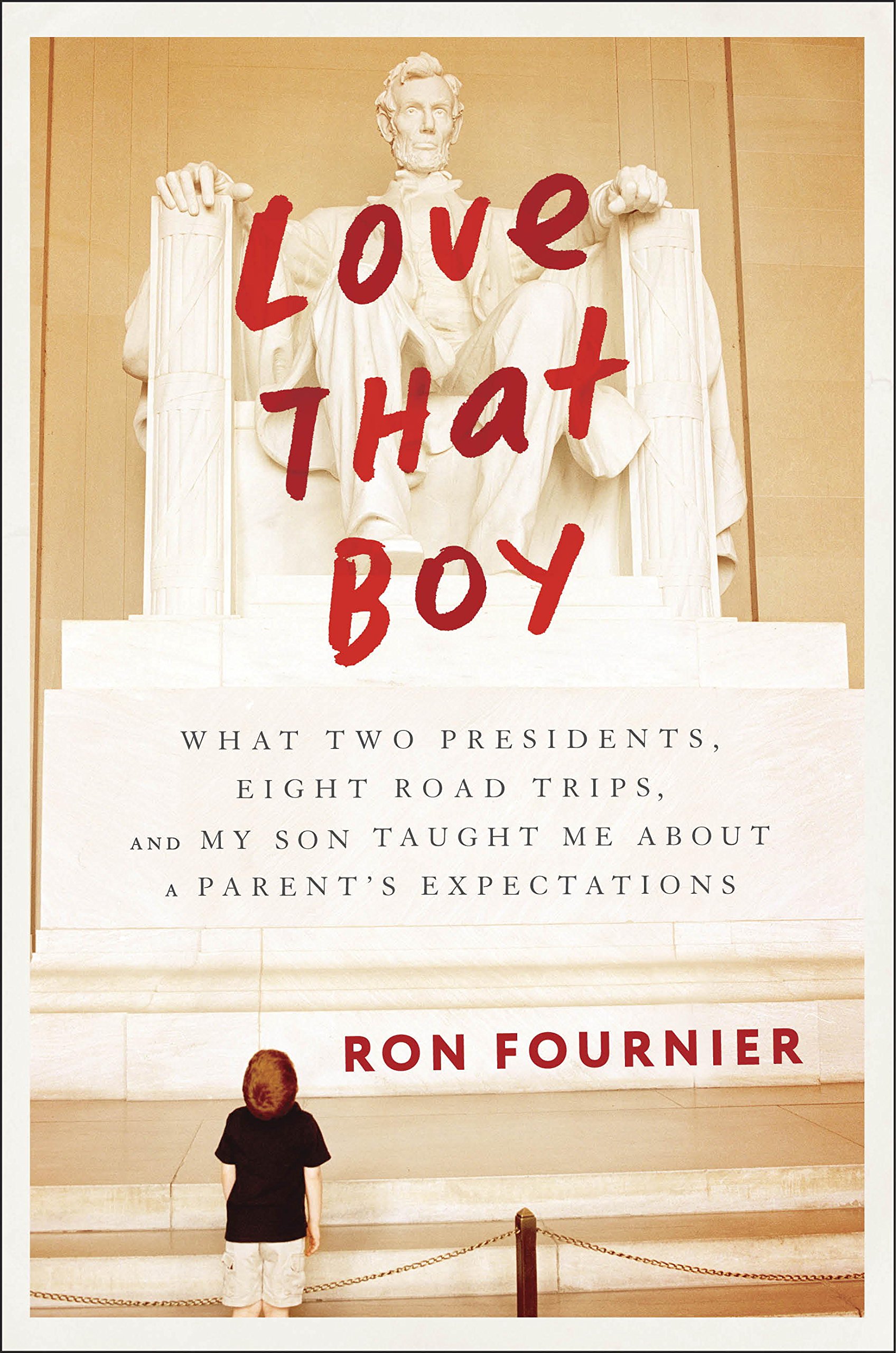

Adapted from Love That Boy: What Two Presidents, Eight Road Trips, and My Son Taught Me About a Parent’s Expectations. (Harmony Books, April 12, 2016).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com