He was a 26-year-old fireman, the head of a family of four. In the year 1900, he was working six days a week, 12 hours a day, all year round. For his labor, he earned $312 a year, the equivalent of a little less than $9,000 today—less than a third of today’s poverty guideline for a family of that size—and 20% less than an average white fireman of the same experience. And yet, with that $312 and money from savings, he had been able to buy a home.

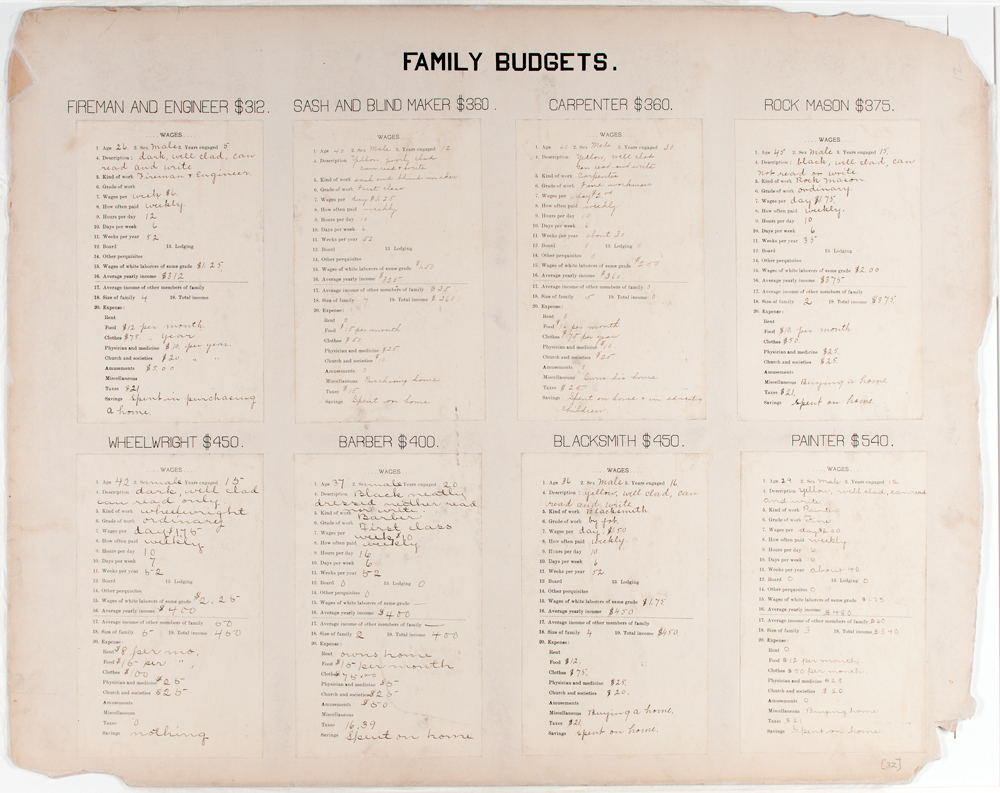

That intimate accounting of life at the turn of the century comes from a display for the “Negro Exhibit” at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900, which was designed to show how African Americans had progressed in the decades since the end of the Civil War. This particular chart shows the family budgets for eight different Georgia families. Roll over or click to zoom:

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The budget comparison paints a rich picture, showing both the depth of poverty and discrimination that a black family might experience along with signs of progress. At the high end, for example, a painter earning $540 a year estimated that his $2-a-day wages were a quarter higher than the wages of a white painter at the same level. It’s also notable what that money went to purchase: home ownership was high among the population surveyed, but several of the families allotted not one cent to leisure and amusements.

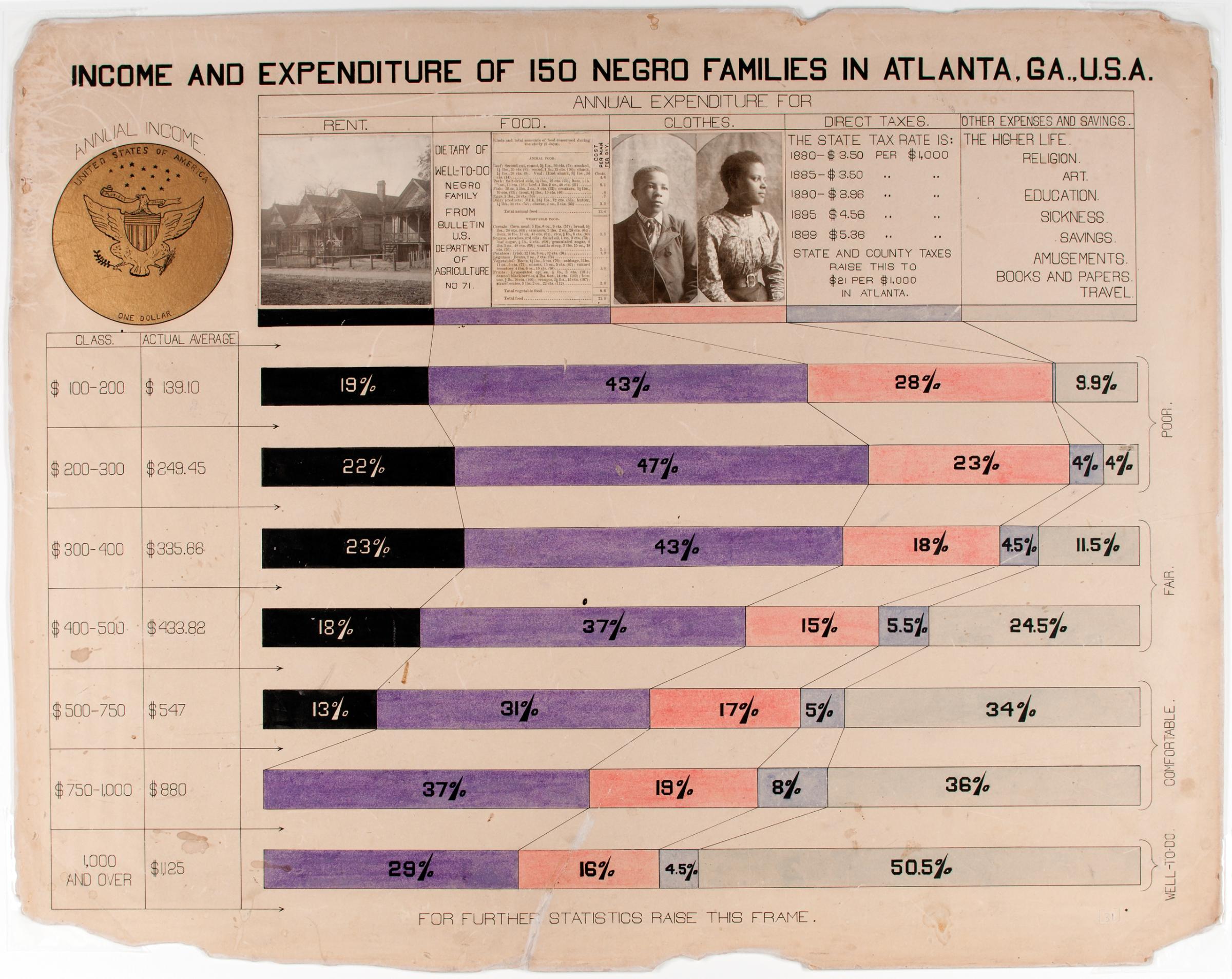

The exhibit, which was created with the help of the renowned academic and activist W.E.B. DuBois, relied on dozens of charts, 500 photographs and a variety of other documents to paint a picture of black life in America at the turn of the century. For example, in the chart at left, which can be expanded by clicking here, the budgets of families at various tax brackets are broken down into expense categories. While rent and food ate up most of the income earned by the lower brackets, a high-income black family in Atlanta in 1900 might have spent more than half of their outlay on the “other” category that included art, education, amusements, travel and savings.

As DuBois wrote at the time, the exhibit was “sociological in the larger sense of the term—that is, is an attempt to give, in as systematic and compact a form as possible, the history and present condition of a large group of human beings.” The focus on Georgia had been chosen, he explained, because its large black population made it ripe for study—though as far as states went, he acknowledged, the picture it presented would not exactly be “rose-colored.” Alongside that data, the exhibit also highlighted achievements in black education and literature.

And, he said, the honest picture of black life in America in 1900, presented “without apology or gloss,” ought to be seen as an encouraging one despite its harsh realism: the African American population was “studying, examining, and thinking of their own progress and prospects.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com