When Cassius Clay answered the telephone one day in early June 1962, he had no idea that the call would change his life. It was Sam Saxon, calling to invite him and his brother Rudy to Detroit for a Black Muslim rally. Over the past year, Cassius had attended more Muslim meetings outside Miami, but he had not yet heard Elijah Muhammad preach in person. With more than five weeks until his next scheduled fight, Clay could afford to spend a weekend with Saxon. So Cassius eagerly accepted his invitation, and a few days later, Sam picked up the Clay brothers in Louisville and drove them to Detroit. There was someone very important Saxon wanted Cassius to meet.

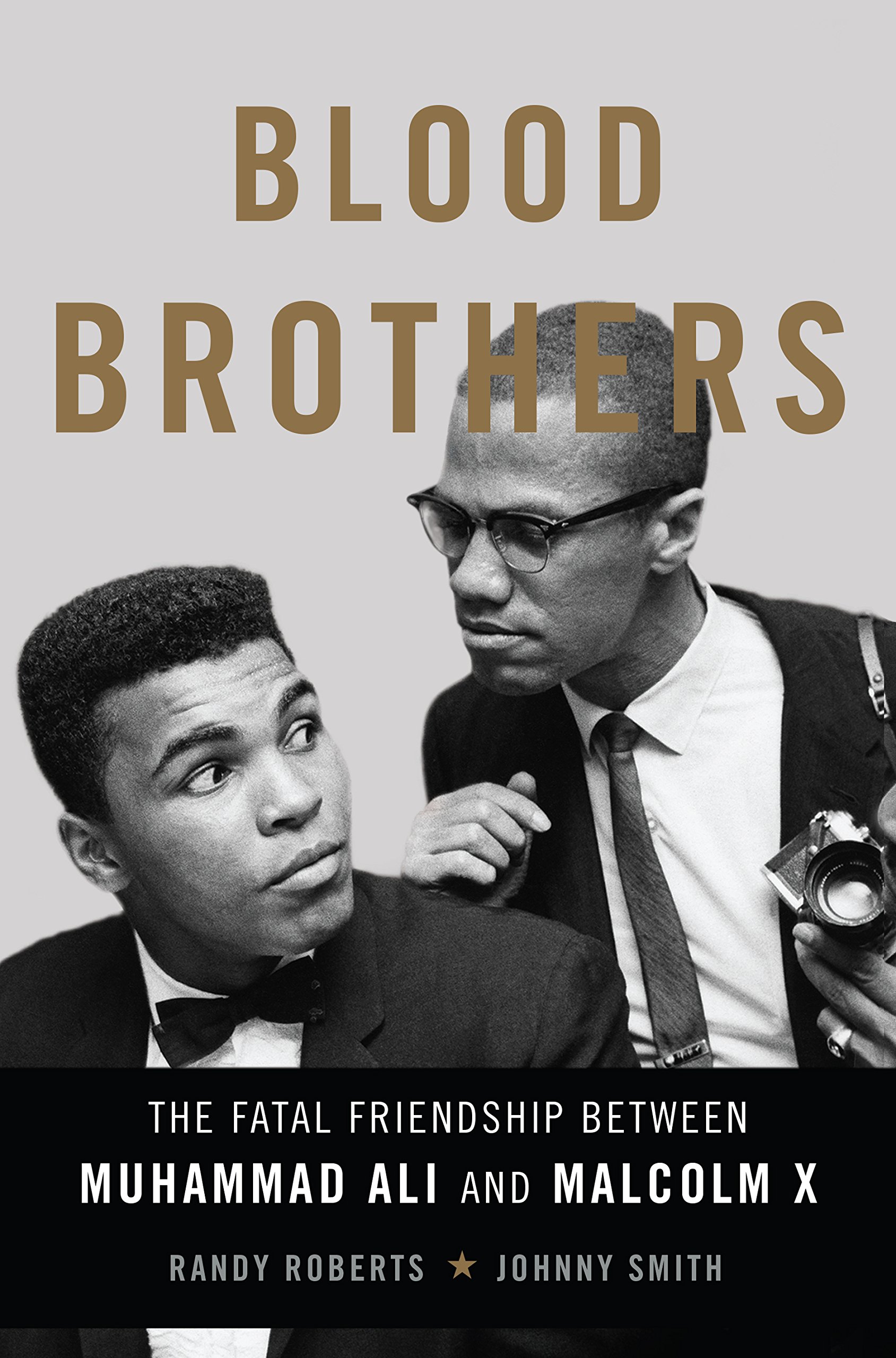

When they arrived on Sunday, June 10, they stopped at a luncheonette crowded with black patrons. Sitting at a back table where he could watch the front door, surrounded by Muslim officers and an assortment of supplicants, Malcolm X noticed Sam Saxon accompanied by two handsome, athletic men walking straight toward his table. Malcolm could see that they were anxious to meet him. One of the brothers, a confident young man with the face of a matinee idol, pumped the minister’s hand and announced, “I’m Cassius Clay,” which he assumed said it all.

For more than two years Cassius had been repeating his name, usually adding that he was “the greatest” and “the prettiest fighter” who had ever laced on a pair of gloves. When Malcolm met the Clay brothers, however, he did not realize that one of them was famous. He had not followed boxing, bet on matches, or read the sports page since he left prison. “Up to that moment . . . I had never heard of him,” he said later. “Ours were two entirely different worlds.” They spoke only briefly, as Malcolm had only a few minutes to finish preparing his opening remarks for the rally. But Clay had already made an impression on him. There was something about the young fighter—some “contagious quality . . . simply a likeable, friendly, clean-cut, down-to-earth” charm— that intrigued Malcolm. He did not know it yet, but he would soon understand that there was a place for Cassius Clay in his world.

That August, after Elijah Muhammad delivered a sermon to a disappointingly small crowd in St. Louis, he attempted to tighten his hold on Malcolm. In a private meeting, Elijah told the increasingly disobedient minister that he disapproved of the way that he deviated from his message, talking publicly about politics and civil rights. In the following months, Muhammad reminded him not to make any more appearances on college campuses without receiving his permission. Before agreeing to let Malcolm speak anywhere, Muhammad wanted to “know exactly how” he would “carry out such a program in advance.”

For a time, Malcolm decided that he should avoid the spotlight. He declined cover story requests from Life and Newsweek and turned down a television interview on Meet the Press. He also noticed that his name and picture disappeared from the pages of Muhammad Speaks after Herbert Muhammad replaced him as editor.

Elijah resented all the attention focused on Malcolm, even though he had made him the Nation’s spokesman. He especially disliked the way that people lionized Malcolm for his intellectual superiority and rhetorical eloquence. Muhammad’s insecurities festered, fueling his paranoia over comparisons to the younger man, who claimed that he had learned everything from Elijah. But unlike Malcolm, Muhammad made grammatical errors in his speeches and stumbled over words he did not recognize. Lacking any formal education beyond the fourth grade, he struggled while reading aloud. His sermons rarely impressed or excited audiences the way that Malcolm’s did. “To be able to listen to Muhammad for any length of time,” one observer commented, “you had to be a believer, convinced in advance.”

Muhammad worried that the controversies surrounding Malcolm’s public appearances would invite closer scrutiny from the government. On August 15, three days after the St. Louis rally, Congressman Francis E. Walter, chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), condemned the Black Muslims as a subversive group influenced by communists and announced that an investigation would begin soon.

When he heard about the HUAC probe, Muhammad became agitated. Although the Muslims were ardent anticommunists, the government suspected that a tinge of red ran through their teachings. It did not help that two years earlier, in Harlem, Malcolm had met with Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro without Elijah’s approval. Castro had been in New York to condemn the United States before the United Nations. At the time Muhammad had suspected that the meeting would come back to haunt him. But Malcolm maintained, “We will welcome any investigation, we have nothing to hide.”

Malcolm may have believed that he had nothing to hide, but Cassius Clay did. A month after HUAC announced that it would investigate the Nation, the heavyweight contender appeared in a photograph at the bottom of a page in the September 15 issue of Muhammad Speaks. Dressed in a dark suit, white shirt, and bow tie, Clay seemed completely comfortable smiling for the camera, as if someone were snapping a picture of him and his brother at a family reunion rather than at a Muslim rally in St. Louis. No one interviewed him for Muhammad Speaks, as athletes received little coverage in the paper. He was not yet considered an important figure in the Muslims’ national agenda, but for the second time in two months he traveled a great distance to hear Elijah Muhammad and to spend more time with Malcolm.

Clay’s fascination with the Nation evolved alongside his growing notoriety as a boxer. At a time when the government planned an extensive, if unwarranted, investigation into the organization, Clay risked his boxing career by associating with the Nation. Remarkably, the blacks who saw him in Detroit and St. Louis never shared that information with reporters. If a black writer recognized him at one of the rallies or noticed his picture in Muhammad Speaks, or a white writer caught wind of him shaking hands with Malcolm X, it could have ended his career.

Adapted from Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2016.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com