In 1949 Los Angeles, a police officer arrested Isidore Edelman as he spoke from a park bench in Pershing Square. Twenty years later, an officer in Jacksonville, Florida, arrested Margaret “Lorraine” Papachristou when she was out for a night on the town.

Edelman and Papachristou had very little in common. Edelman was a middle-aged, Russian-born, communist-inclined soapbox orator. Papachristou was blond, statuesque, twenty-three, and a Jacksonville native. The circumstances of their arrests were different, too. It was Edelman’s strident and offensive speeches that caught the attention of the police—his politics were just too inflammatory for the early Cold War. For Papachristou, it was her choice of companions—she and her equally blonde friend had been out with two African American men in a southern city not quite transformed by the civil rights era.

What Edelman and Papachristou shared despite their differences was the crime for which they were arrested: vagrancy. California law made a vagrant of everyone from wanderers and prostitutes to the willfully unemployed and the lewd. Edelman’s earlier arrests off the soapbox had made him “dissolute” and therefore a vagrant under the law. Papachristou was arrested under a Jacksonville ordinance that criminalized some twenty different types of vagrants, including “rogues and vagabonds, or dissolute persons who go about begging, … persons who use juggling or unlawful games or plays, common drunkards, … common railers and brawlers, persons wandering or strolling around from place to place without any lawful purpose or object, habitual loafers, disorderly persons.” Such a law, noted a judge in 1970, sounded like “a casting advertisement in an Elizabethan newspaper for the street scene in a drama of that era.” To the police, the listed categories did not even exhaust the law’s possibilities. They noted that Papachristou and her companions were vagrants for an improvised and far more modern reason: “prowling by auto.”

As the evocative language of these laws suggests, the crime of vagrancy had long historical roots. Since the 16th century, vagrancy laws had been used in England to uphold hierarchy and social order. Despite much-touted myths of American upward and outward mobility, the laws proliferated along with English colonists on this side of the Atlantic too. Indeed, when Edelman was arrested in 1949, vagrancy was a crime in every state and the District of Columbia.

Two features of vagrancy laws made them especially attractive. First, the laws’ breadth and ambiguity gave the police virtually unlimited discretion. Because it was almost always possible to justify a vagrancy arrest, the laws provided what one critic called “an escape hatch” from the Fourth Amendment’s protections against arrest without probable cause. As one Supreme Court justice would write in 1965, vagrancy-related laws made it legal to stand on a street corner “only at the whim of any police officer.”

Second, vagrancy laws made it a crime to be a certain type of person—anyone who fit the description of one of those colorful Elizabethan characters. Where most American laws required people to do something criminal before they could be arrested, vagrancy laws emphatically did not.

Armed with this roving license to arrest, officials employed vagrancy laws for a breath-taking array of purposes: to force the local poor to work or suffer for their support; to keep out poor or suspicious strangers; to suppress differences that might be dangerous; to stop crimes before they were committed; to keep racial minorities, political troublemakers, and nonconforming rebels at bay. As these uses suggest, vagrancy laws were linked to a conception of postwar American society—as they had been linked to a conception of sixteenth-century English society—in which everyone had a proper place. The vagrancy law was often the go-to response against anyone who threatened, as many described it during vagrancy laws’ heyday, to move “out of place” socially, culturally, politically, racially, sexually, economically, or spatially. Over time, states and localities deployed and retooled vagrancy laws for use against almost any—real or perceived, old or new—threat to public order and safety.

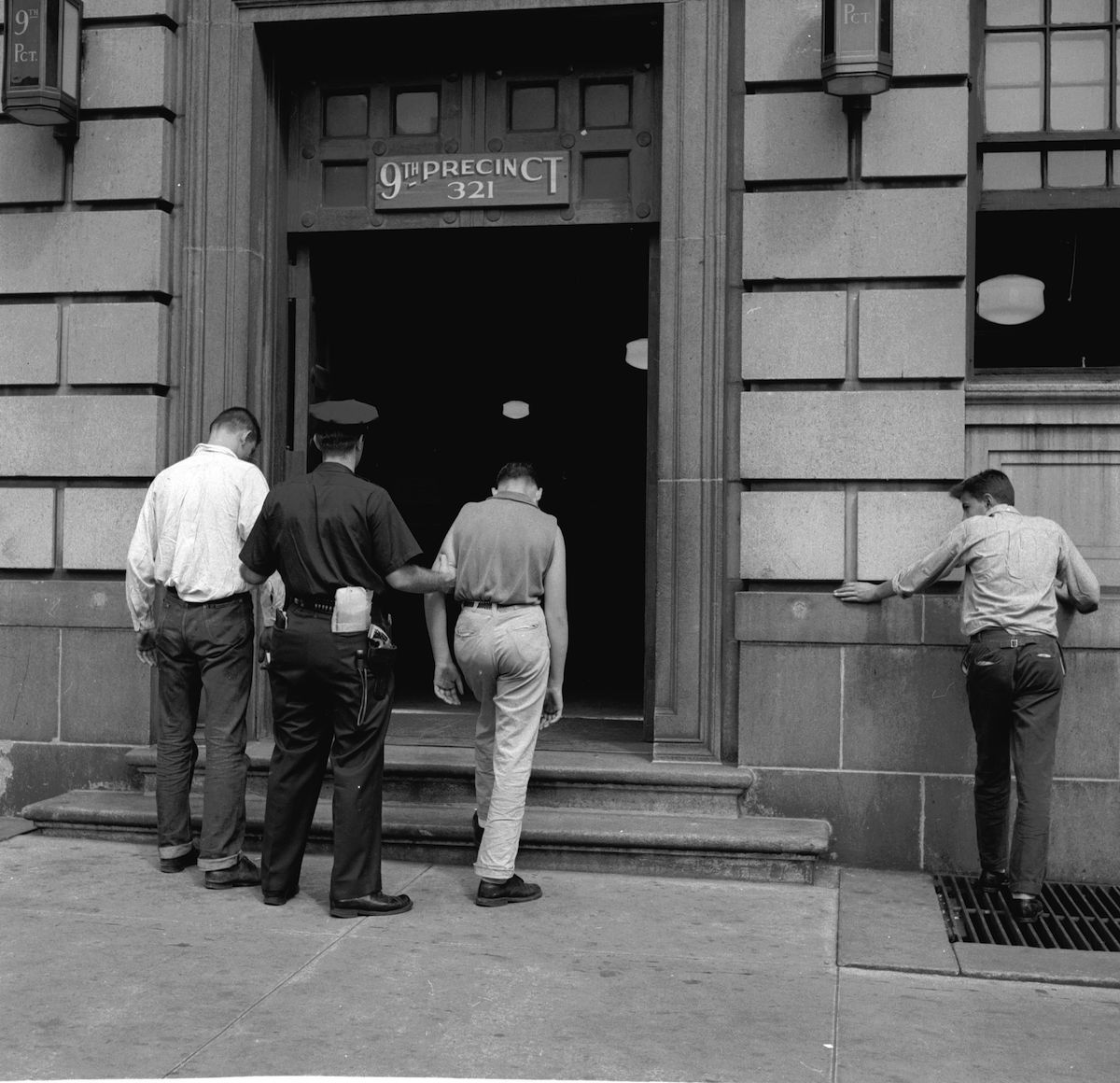

The officer on the beat in the 1950s and 1960s saw such threats everywhere, in the “queer,” the “Commie,” the “uppity” black man, the “scruffy” young white one. It was his job to see these threats, to determine who was “legitimate” and who not. He was trained to see difference as dangerous, to see the unusual as criminal. That was what not only his superiors but also the upstanding taxpayers wanted, expected him to do. When he walked the streets questioning and arresting the scum, the flamboyant, the detritus, and the apostate, he brought vagrancy laws with him, and he did his job.

Between Edelman’s arrest and Papachristou’s twenty years later, literally millions of people shared their vagrancy fates. Some of those arrested comported with the usual image of the vagrant. Sam Thompson, for example, was an under-employed handyman and alcoholic arrested some fifty-five times in Louisville, Kentucky, in the 1950s. But many, like Edelman and Papachristou, are more surprising. The police arrested for loitering the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, co-founder with Martin Luther King Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, when he spoke briefly with colleagues on a Birmingham street corner during a 1962 department store boycott. It was vagrancy the police used when they could not get Tulane law student Stephen Wainwright to cooperate with a murder investigation in New Orleans’ French Quarter in 1964. It was vagrancy as well that justified the 1966 arrest of Martin Hirshhorn, a young cross-dressing hair stylist arrested in his hotel room in Manhattan wearing only a half-slip and brassiere. Police turned to vagrancy in 1967 when they arrested Joy Kelley in the “crash pad” she had rented for herself and her hippie friends in Charlotte, North Carolina. And they used it again when they mistook Dorothy Ann Kirkwood for a prostitute when she was on her way to meet her boyfriend on Memphis’s famous Beale Street in 1968.

These and other vagrancy suspects were white and black, male and female, straight and gay, urban and rural, southern, northern, western, and midwestern. They had money or needed it, defied authority or tried to comply with it. They were arrested on public streets and in their own homes; as locals or strangers; for political protests or seeming like a murderer; for their race, their sexuality, their poverty, or their lifestyle.

Vagrancy laws were thus not only a fact of the legal landscape in the middle of the twentieth century. They were also a fact of life for countless Americans. Working-class immigrant families warned their maturing children not to leave home without money that could inoculate them from vagrancy arrests. Early “homophile” organizations educated their gay and lesbian members about “lewd vagrancy” arrests and how to avoid them—“wear at least three items of clothing of your own sex” was a common refrain. Black newspapers warned their readers that vagrancy arrests were a likely consequence of any racially presumptuous behavior. Civil rights organizations tried to head off seemingly inevitable vagrancy arrests of workers heading south by providing “vagrancy forms” that attested to the workers’ standing as “reputable member[s] of the community.”

The vagrancy law regime, then, regulated so much more than what is generally considered “vagrancy.”

That was all about to change. The case that followed Edelman’s 1949 arrest marked a new era in the history of vagrancy laws. Though Edelman himself did not emerge victorious, his case both signaled and set in motion a process of rapid and fundamental legal transformation. Laws on the books for four centuries were now, suddenly, on the constitutional defensive. Over the next twenty years, alleged vagrants and their lawyers, social reformers, activists, the media, state legislators, state and lower federal courts, and, somewhat belatedly, the Supreme Court condemned vagrancy laws and their uses. Even the laws’ fiercest defenders—the police who relied on them—substantially narrowed their justifications for the laws’ legitimacy. In a trio of cases in 1971 and 1972, including Papachristou’s own, the Court announced that vagrancy, loitering, and suspicious persons laws were unconstitutional.

That shift is impossible to separate from the major upheavals that convulsed American legal, social, intellectual, cultural, and political life between the 1950s and the 1970s. Those who had long lacked social and political power began to organize, march, and protest; stand fast before fire hoses and riot gear; hire lawyers and bring appeals. In doing so, they projected a new image of American society in which vagrancy policing was anathema.

As may already be apparent, the age-old crime of vagrancy became a flashpoint in virtually every great cultural controversy of the time. From sexual freedom to civil rights, from poverty to the politics of criminal justice, from the Beats to the hippies, from communism to the Vietnam War, the great issues of the day all collided with the category of the vagrant. Vagrancy, police power, and the Constitution met on streets and parade grounds, skid rows and lunch counters, at polite sit-ins, militant protests, and outright riots. Wherever the sixties happened, vagrancy law was there.

Adapted from Vagrant Nation: Police Power, Constitutional Change, and the Making of the 1960s by Risa Goluboff with permission from Oxford University Press, Inc. Copyright © 2016 by Oxford University Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com