The Zika virus has spread rapidly across the Americas, arriving in Brazil last May and creeping into 22 other countries and territories around the region. The virus’ spread has been accompanied by a steep increase in babies born with abnormally small heads and in cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome, an uncommon nervous system disease. This has raised the alarm among public health officials around the world—and launched the quest for a vaccine that could stop its spread.

The U.S. and international governments are pushing forward with programs for Zika vaccines, and at least three pharmaceutical companies are either considering or actively pursing programs, including giants GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi . But the company that appears to be the farthest along is a relatively small $500 million market cap biotech named Inovio Pharmacuetucals. Wall Street has shown interest in the company. Inovio’s stock was up about 8% today on news that it is entering clinical trials with its MERS vaccine, which could also hold promise for a future Zika vaccine.

Nonetheless, even Inovio is likely a ways off from developing a human Zika vaccine.

“It is important to understand that we will not have a widely available, safe, and effective Zika vaccine this year, and probably not even in the next few years,” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said in a press conference.

The advantage of Zika vaccine programs is that they can use similar mosquito-based diseases, part of a family called flaviviruses, like dengue, West Nile virus, and chikungunya as a “jumping off” point. While researchers are currently trying to learn more about the basics of the Zika virus and its effects on the human body given how new the disease is, they can already use past vaccine development platforms from other flaviviruses as a foundation since they spread in similar ways.

NIAID is already working on two approaches: a DNA-based vaccine, similar to a strategy used for West Nile virus, which has been found safe and effective in a phase one trial. It is also working on a more traditional killed virus-vaccine, similar to those already developed to prevent dengue.

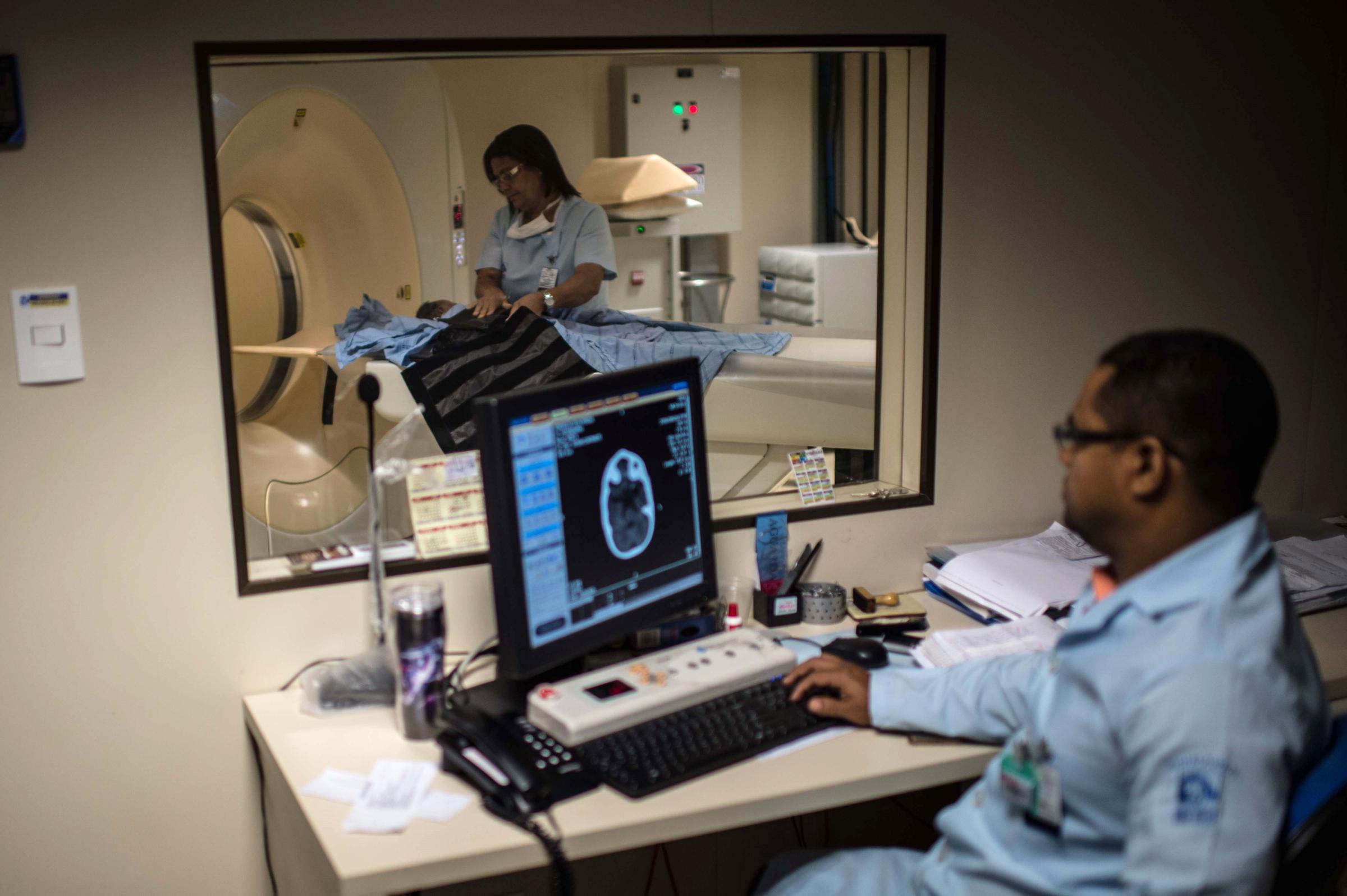

See the Impact of Zika in Brazil

Traditional killed-virus vaccines, also called live-attenuated vaccines, are what most of us are used to. They are grown in eggs using live viruses, and then made inactive by a chemical process, and are the basis for the vast majority of vaccines we take as children and annually to prevent the flu. They are time intensive to develop, typically requiring between 10 and 15 years before they are approved, according to GlaxoSmithKline.

DNA-based vaccines, on the other hand, can reduce that development time by creating a synthetic DNA sequence in a lab that can trigger the human body to create the same antigens as from a killed virus. This cuts development time since it doesn’t need to grow a live virus, which can have unpredictable development pathways.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals has also been working on a DNA-based vaccine for Zika since December. In that time, Inovio has created a DNA strand that can potentially prevent the virus, using its knowledge from its dengue virus program. It is now testing the vaccine in mice and plans to move into testing primates “in the next few weeks,” said Inovio CEO J. Joseph Kim. Once its safety is confirmed, the vaccine will move into phase one testing in humans—as soon as the end of 2016.

“The beauty of this technological platform is that the vaccine is simply a DNA sequence developed in water,” said Kim. “It cuts through all the difficult handling and complex development times of traditional vaccine approaches.”

Inovio has taken this same approach with an Ebola vaccine, going from “bench to clinic”—researcher terms, meaning from initial creation to human testing—in just over 18 months. That program attracted the interest of the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which gave the company $45 million to support the program’s ongoing development. The biotech is also working on a DNA-based vaccine for MERS, which has gone from its creation in a lab to a phase one trial at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in just over a year.

Still, while animal applications of these preventatives have been approved in animals, DNA-based vaccines are one of the latest medical advancements, and one has yet to be approved for use in humans in the U.S. Even though Inovio has attracted fans on Wall Street, it still has a lot to prove.

This article originally appeared on Fortune.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com