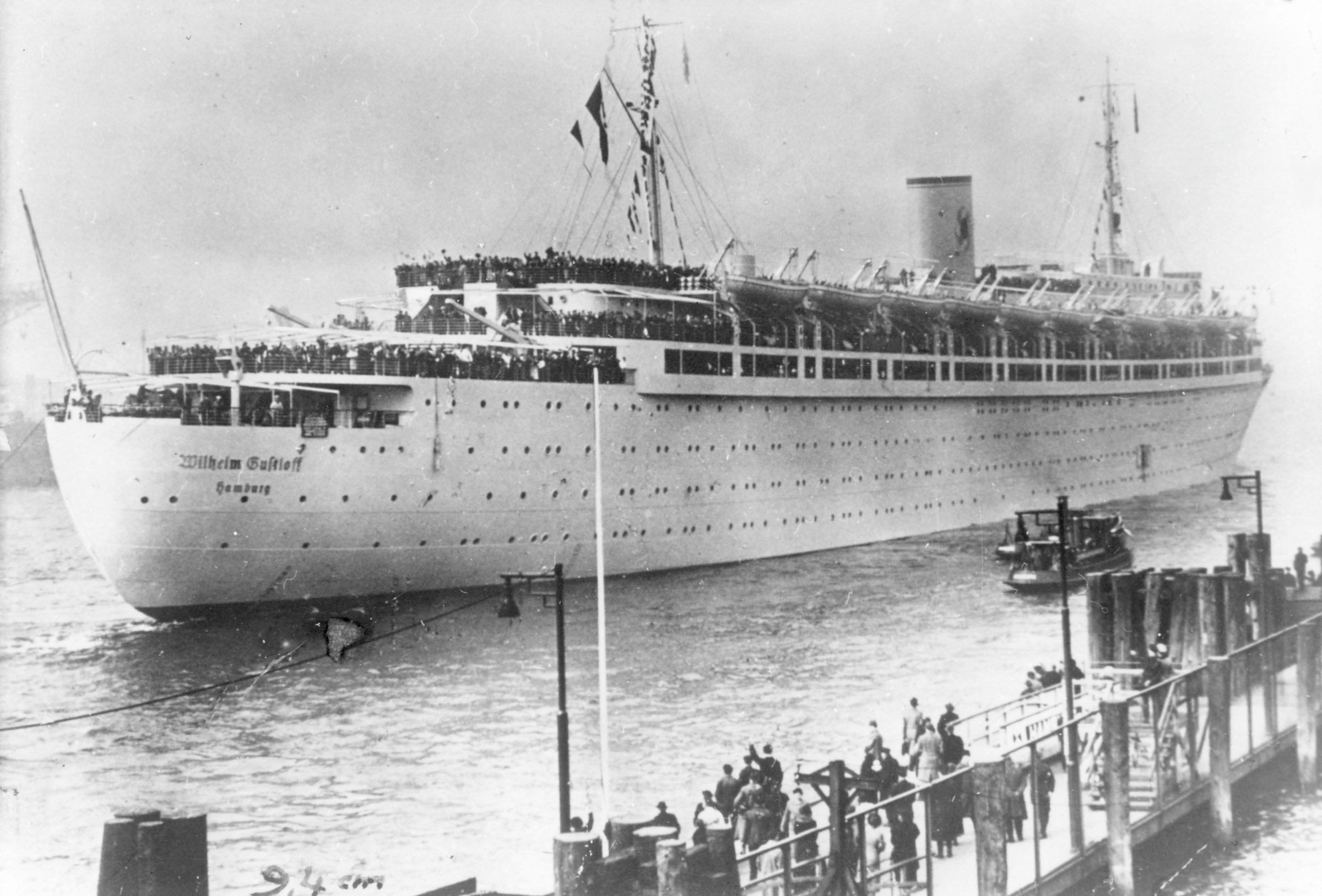

The sinking of the Titanic may be the most infamous naval disaster in history, and the torpedoing of the Lusitania the most infamous in wartime. But with death counts of about 1,500 and 1,200 respectively, both are dwarfed by what befell the Wilhelm Gustloff, a German ocean liner that was taken down by a Soviet sub on Jan. 30, 1945, killing 9,343 people—most of them war refugees, about 5,000 of them children.

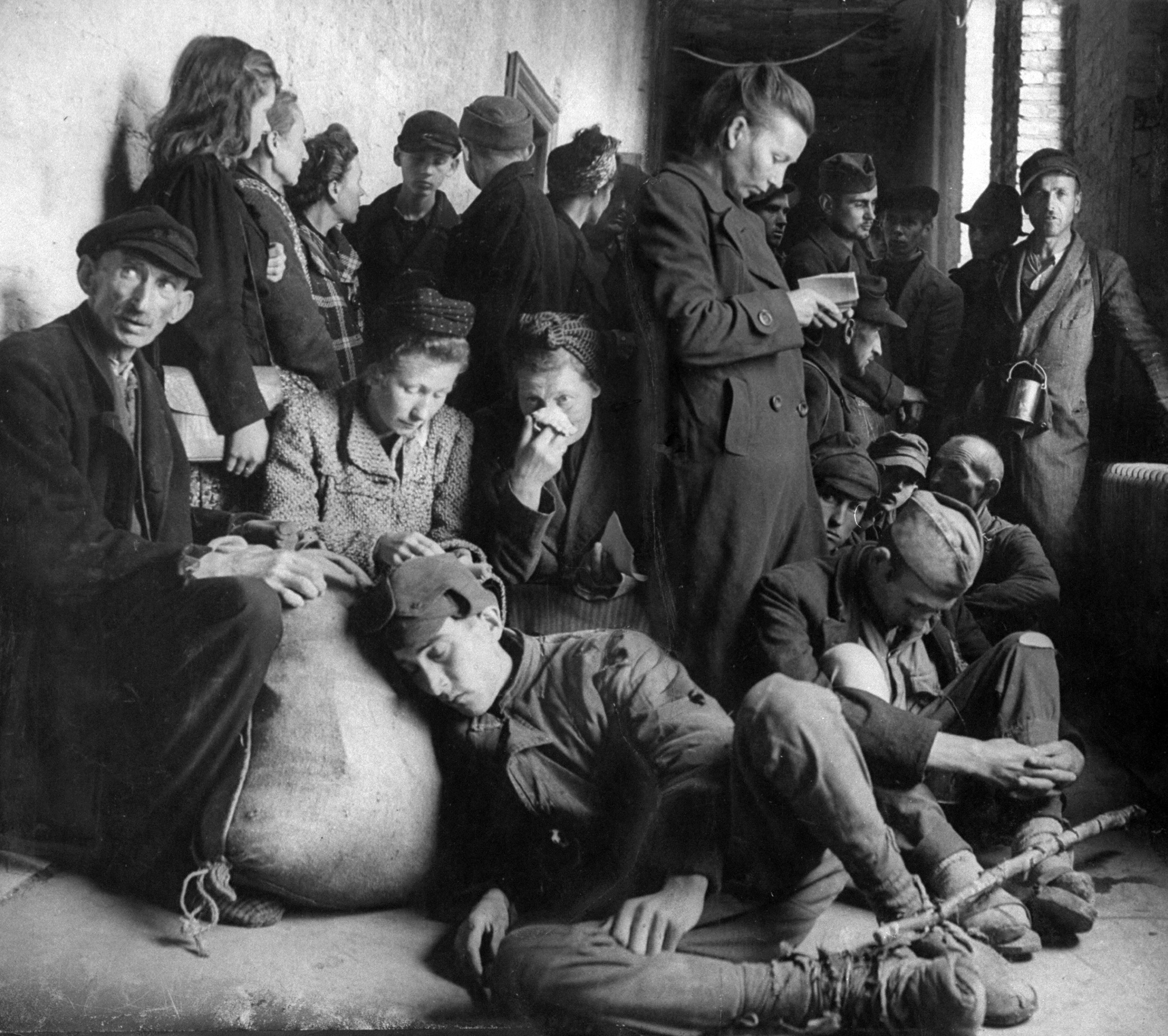

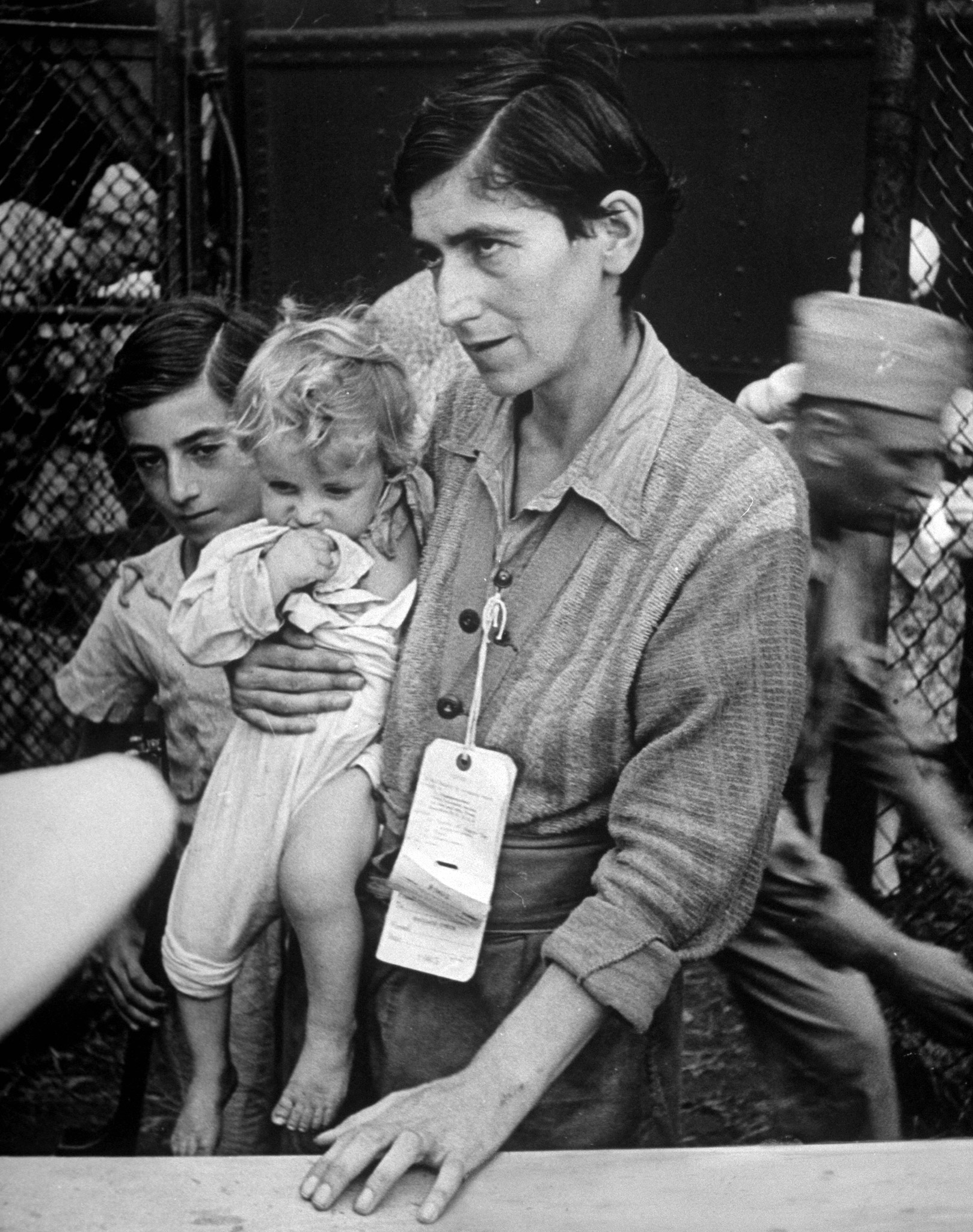

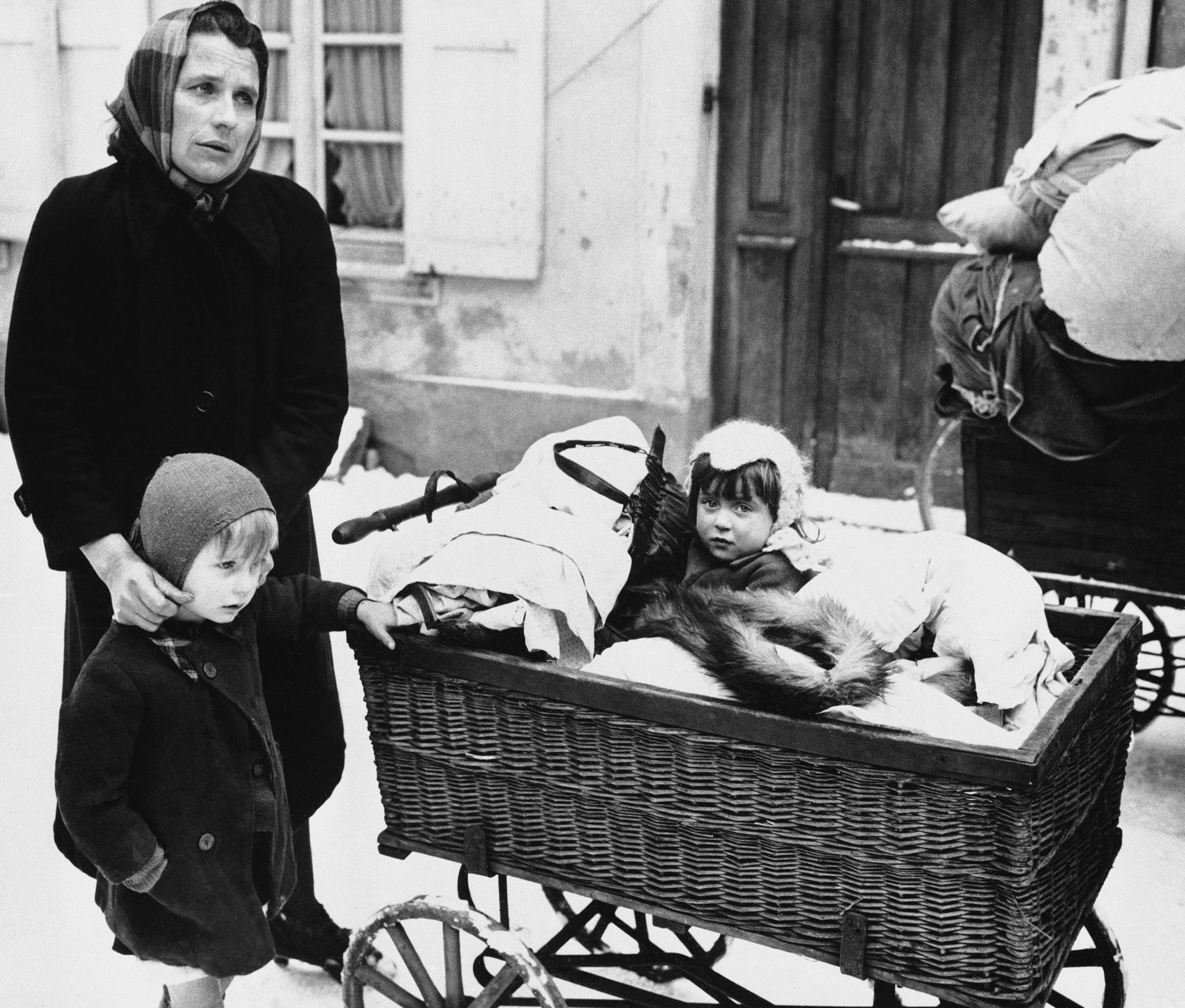

The victims of the worst maritime tragedy in history were not only Germans, but also Prussians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Poles, Estonians and Croatians. World War II was drawing to an end, and the Soviet army was advancing. Though it would be months before the final fall of the Nazi regime, it was clear the end was coming—and they were desperate to escape before things came to a head. As a result, 10,582 people were packed onto a cruise ship that was meant to accommodate only about 1,900. Though some on the ship were Nazis themselves, others had been the victims of Nazi aggression. When three torpedoes hit the ship, there weren’t nearly enough lifeboats, and many of the those that did exist were frozen to the deck. The majority of the passengers drowned.

Why is this event so little known? Novelist Ruta Sepetys can’t say for sure, but its obscurity made it exactly the kind of story she wanted to tell. The author has written a book for young readers called Salt to the Sea, out Tuesday, about four fictional young passengers on the Wilhelm Gustloff: an overeager Nazi manning the ship; a Lithuanian nurse doing her part but haunted by her past; a Polish girl concealing her nationality and the source of her pregnancy; and a Prussian carrying something Hitler wants.

Sepetys, an international bestseller thanks to her first novel Between Shades of Gray (which shares a character crossover with Salt to the Sea) is drawn to “hidden histories.” She looked into the Wilhelm Gustloff after finding out that a cousin of hers would have been on board were it not for a last-minute decision to delay the travel, a choice that the cousin had feared would prove the wrong one. As it departed, “she was standing in the port crying, thinking that her life was over,” Sepetys says. The decision likely saved her life, in fact.

Intrigued, Sepetys immersed herself in research, particularly relying on the book Death in the Baltic but also on firsthand accounts from survivors she interviewed. “I hope this doesn’t sound too dramatic,” she says, “but what surprised me the most was that anyone survived.”

With the help of her publisher in Poland, she even tracked down two divers who had explored the wreck in the late ’60s under Soviet supervision. The Soviets were allegedly curious to see if the Germans had tried to use the refugee ship to evacuate treasure, too. “They did not share with me exactly what they brought up,” Sepetys says, “but yes, things were retrieved. And then there were instructions to detonate parts of the ship, because it was considered an obstruction in the water.”

So why do so few people know about the Wilhelm Gustloff? Sepetys has a couple of theories. First, the Nazi regime actively tried to hide the facts. “They were amidst an evacuation and they didn’t want it to affect morale. They also were trying to hide the fact they were losing the war,” she says. “Some survivors reported that when they spoke of it, there was a knock on their door, and they were told, ‘Why are you telling stories about some ship? That didn’t happen.'”

In the aftermath of the war, she adds, Germans were hesitant to claim that they had been victims of any kind, so those who were free to discuss what had happened might have chosen not to.

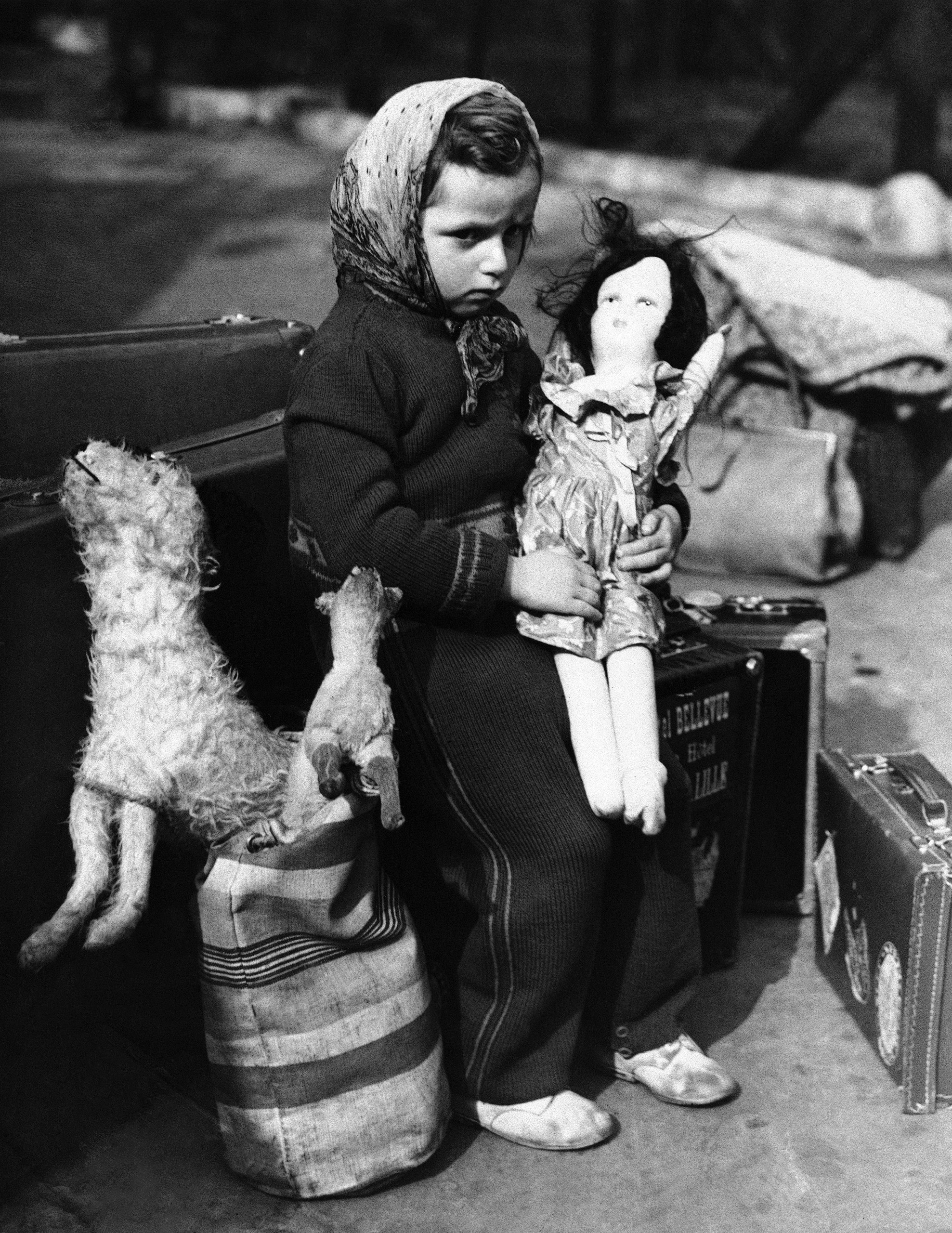

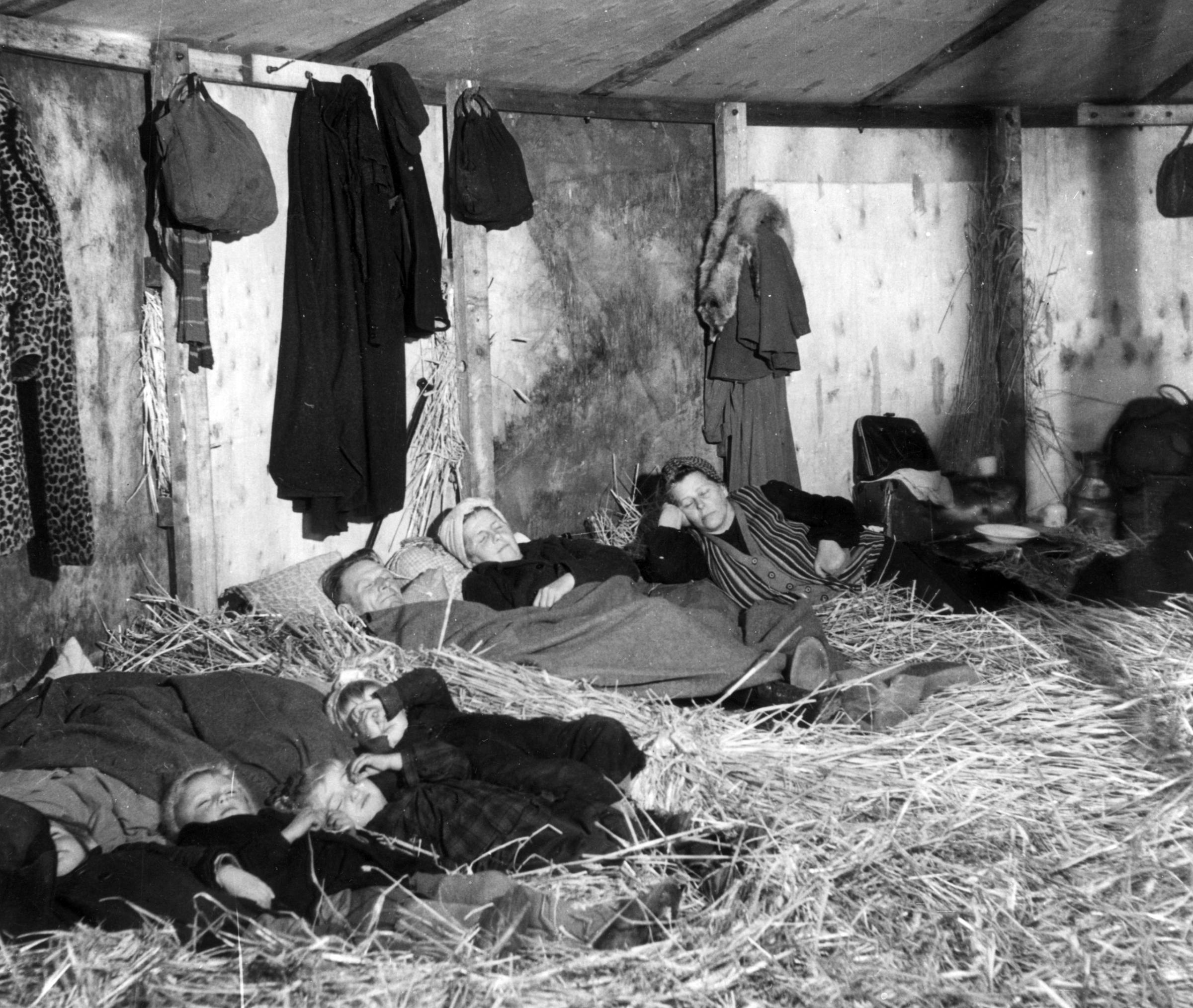

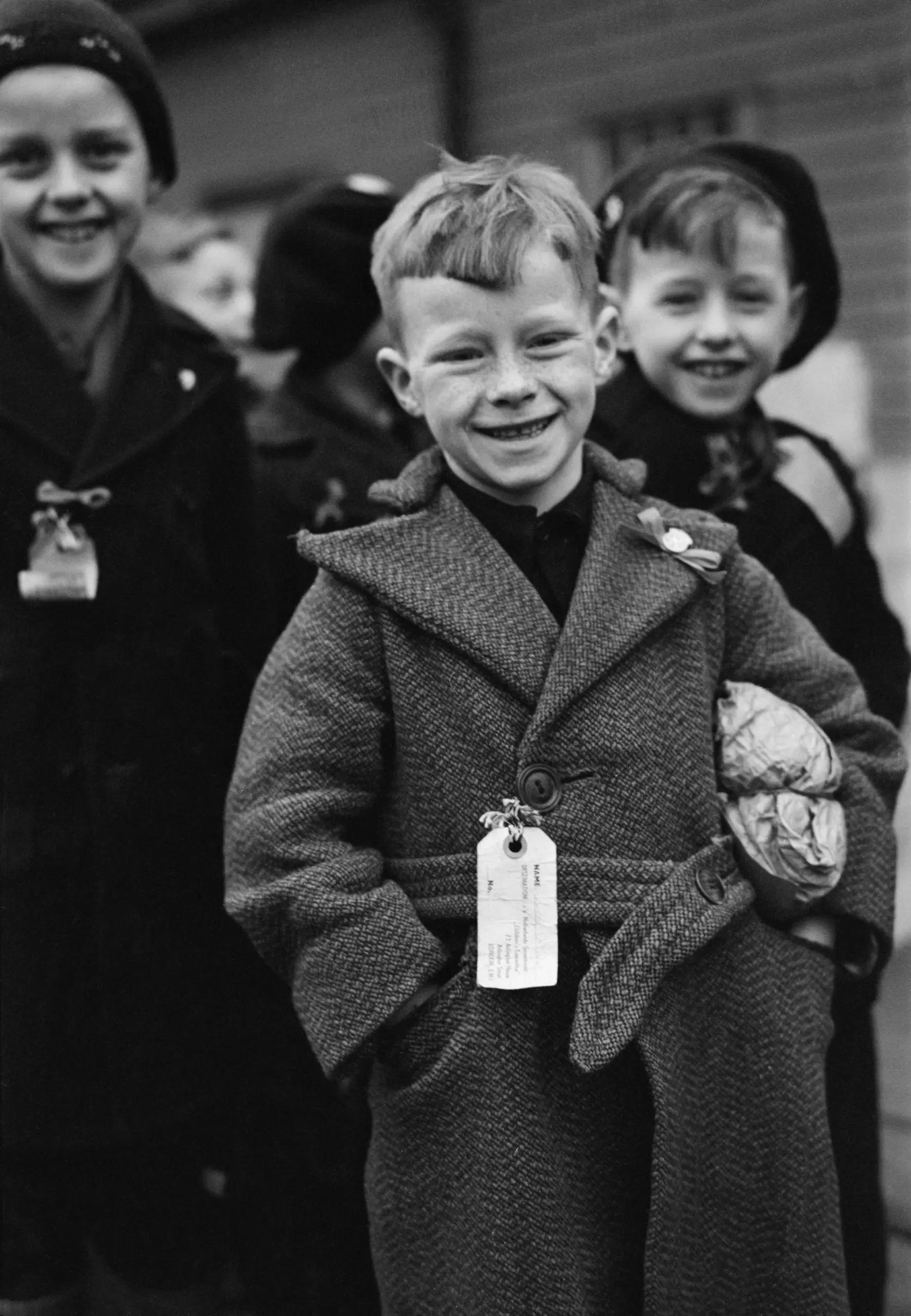

This Is What Europe’s Last Major Refugee Crisis Looked Like

Another reason, she says, “could be that the submarine captain [who sank the ship], Alexander Marinesko, was dishonorably discharged shortly after,” apparently for disorderly conduct. At the time, Sepetys guesses, the Russians did not want to draw attention to him—though in later years monuments would be dedicated to his naval valor.

The Wilhelm Gustloff interested Sepetys as a story about refugees because her own Lithuanian father spent nine years in refugee camps before being settled in the U.S.—but she had no idea when she began her work that the story would prove relevant on a global scale, as the current influx of migrants in Europe draws comparisons to the migrations of the past. The author hopes getting to know her protagonists could help young readers and grown-ups alike empathize with people in situations far from their own. “Many families don’t have recent experience or connection to occupation or war,” she says. “But through story and characters, suddenly news and history become human.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com