Even in America’s convoluted political system, the Iowa caucuses stand out as being mysterious to the average non-Iowan.

But with the Hawkeye State poised to be the first in the nation to cast votes on the Democratic and Republican presidential nominations, it’s a good time for a refresher.

Here are some answers to questions you may have about the Iowa caucuses.

What are caucuses?

They’re sort of a cross between a normal election and a town-hall meeting, though the exact format differs for both parties. For Republicans, caucus-goers will go to a meeting where they will hear speeches from local representatives of the presidential campaigns, then cast their vote by writing the name of their preferred candidate on pieces of paper, which are then tallied and reported to the state party. Democrats will also go to meetings, but they’ll sit in different parts of the room based on who they support. If a particular candidate doesn’t get at least 15% of the people in the room, the voters in that section can move to a different candidate—essentially an in-person version of an instant-runoff election. Once there are no non-viable groups left, the results are final and the totals in each group used to divvy up that precinct’s delegates, which are then reported to the state party.

What’s the difference between the Democratic caucuses and the Republican ones?

Besides the viability thresholds, the Democratic caucuses are public—everyone in attendance knows whom everyone else is supporting—compared to a secret ballot for Republicans. Additionally, Republicans report the raw vote totals, while Democrats only report delegate totals. Delegate apportionment rules are designed to equalize the support of two roughly even challengers, while the raw vote results allow a more lopsided distribution of delegates at the statewide level.

Read More: Sanders Campaign Questions Microsoft’s Role in Caucus Reporting

Why do the Iowa caucuses matter?

Because it’s the first time that voters will have a chance to narrow the field of candidates. The months leading up to the caucuses are part of the so-called “shadow primary” in which donors, grassroots supporters and members of each party’s Establishment help determine which campaigns live or die. But Iowa marks the first time that voters have a say. If candidates can’t start attracting votes, donations will dry up, volunteers will lose hope and political insiders will start encouraging candidates to move on.

See Pictures From a Week of Campaigning in Iowa

What role has Iowa played in previous presidential elections?

Iowa is all about demonstrating political viability, though in very different ways to both parties. They are more important to Democrats, where Iowans have correctly picked the nominee every cycle since 1996, than for Republicans, where social conservatives have swung to caucuses in the last two cycles for candidates who had little real chance of winning the nomination.

In 2004, former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee won Iowa but the former pastor saw his candidacy quickly fade after a poor showing in New Hampshire and he won only seven other states. Likewise, in 2012 former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum won Iowa on a pro-life, pro-family platform, but he only won three more states before dropping out.

On the Democratic side, surprise Iowa wins gave former Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry in 2004 and former Illinois Sen. Barack Obama in 2008 momentum and proved their viability. Both went on to win the nomination. That said, this time around, Iowans could flip their logic. On the Republican side, front runner Donald Trump is ahead in the polls in the Hawkeye State and dark horse Democratic socialist Bernie Sanders is neck-and-neck with Hillary Clinton. But even if Sanders won Iowa, he’d remain a longshot for the nomination.

How many people will turn out?

Turnout is the million dollar question in Iowa. Historical turnout for contested Republican caucuses has been about 120,000. For Democrats, in 2008, about 230,000 showed up as Barack Obama dramatically expanded the pool of caucus-goers. Republicans are preparing for a turnout as high as 150,000 this cycle, though most expect around 130,000 to show up. (More than 140,000 would mean an almost-certain Trump victory, indicating he had significantly expanded the universe of caucus-goers.) A turnout similar to 2008 would be a strong sign of support for Sanders, though many expect slightly fewer to show up this time around.

Who has campaigned the most in Iowa?

After Santorum won the 2012 Iowa caucuses, it’s almost like he never left. Nobody has spent as many days campaigning in Iowa (more than 90) since then as Santorum, nor held as many events (he’ll be at nearly 300 by Caucus Day). The former Pennsylvania Senator was also the first GOP candidate to hit all of the Hawkeye State’s 99 counties, a feat known locally as the “full Grassley” (after Iowa’s senior senator, Chuck Grassley). Not that it’s helped: the latest RealClearPolitics polling average puts the reigning Republican caucus champion at 1%—last place in the GOP field.

Who will win the Iowa caucuses?

It’s quite possible that no one wins these contests in the traditional sense of the word. The small share of registered voters who turn out to huddle on a cold February night only set in motion the process by which parties divvy up delegates to the nominating conventions. Even then, there are relatively few delegates at stake. The major upside is headlines coming out of Iowa. Of the 2,472 total delegates to the GOP convention in Cleveland, 30 are decided in Iowa’s caucuses.

Does winning matter?

Winning matters less than losing. Candidates who make Iowa their first all-in state and then come up short will leave Iowa embarrassed if they don’t meet expectations. Iowa typically winnows the field, and it serves the very important function of whittling away candidates who aren’t built for the long haul. Winners typically see an onslaught of press coverage—and scrutiny. But, historically speaking, winning in Iowa all but guarantees a loss in New Hampshire. New Hampshire voters simply do not ratify Iowa’s results. The candidates who fail to live up to the hype in Iowa are typically the first to exit the race.

Who will be hurt the most?

Republican candidates who are forced far to the right to win Iowa tend to fare poorly after decamping from Des Moines. The Iowa GOP electorate is deeply conservative and very religious—far more than the national voter. To win in Iowa, candidates typically occupy the farthest to the right position they can find. That hurts them down the calendar in more moderate or secular states, as well as if they are the nominee. For Democrats, the state urges a populist posture, one that conservative super PACs can exploit ahead of November’s general election.

What are the biggest policy issues in Iowa, compared to other states?

The biggest federal policy issue in Iowa is and, it seems, always has been corn. Specifically, the issue is whether the federal government should continue to subsidize farmers who grow corn, much of which is used to make ethanol, an alternative fuel. Conservatives generally don’t love the idea of government subsidies, which distort the free market, but woe unto he who threats the Hawkeye State’s top crop. This year, Ted Cruz, who opposes energy subsidies of all kinds, has earned the ire of the state’s powerful pro-ethanol lobby and has battling negative radio ads funded by the group.

Read More: How Ted Cruz Tried to Reframe the Ethanol Debate

What role does religion play among Iowa voters?

Religion matters in Iowa. Four out of five adults in Iowa are Christians, according to the Pew Research Center. Nearly all are white, and half attend church weekly—more than a quarter of Iowans are evangelical Christians, and those are more likely to be Republicans.

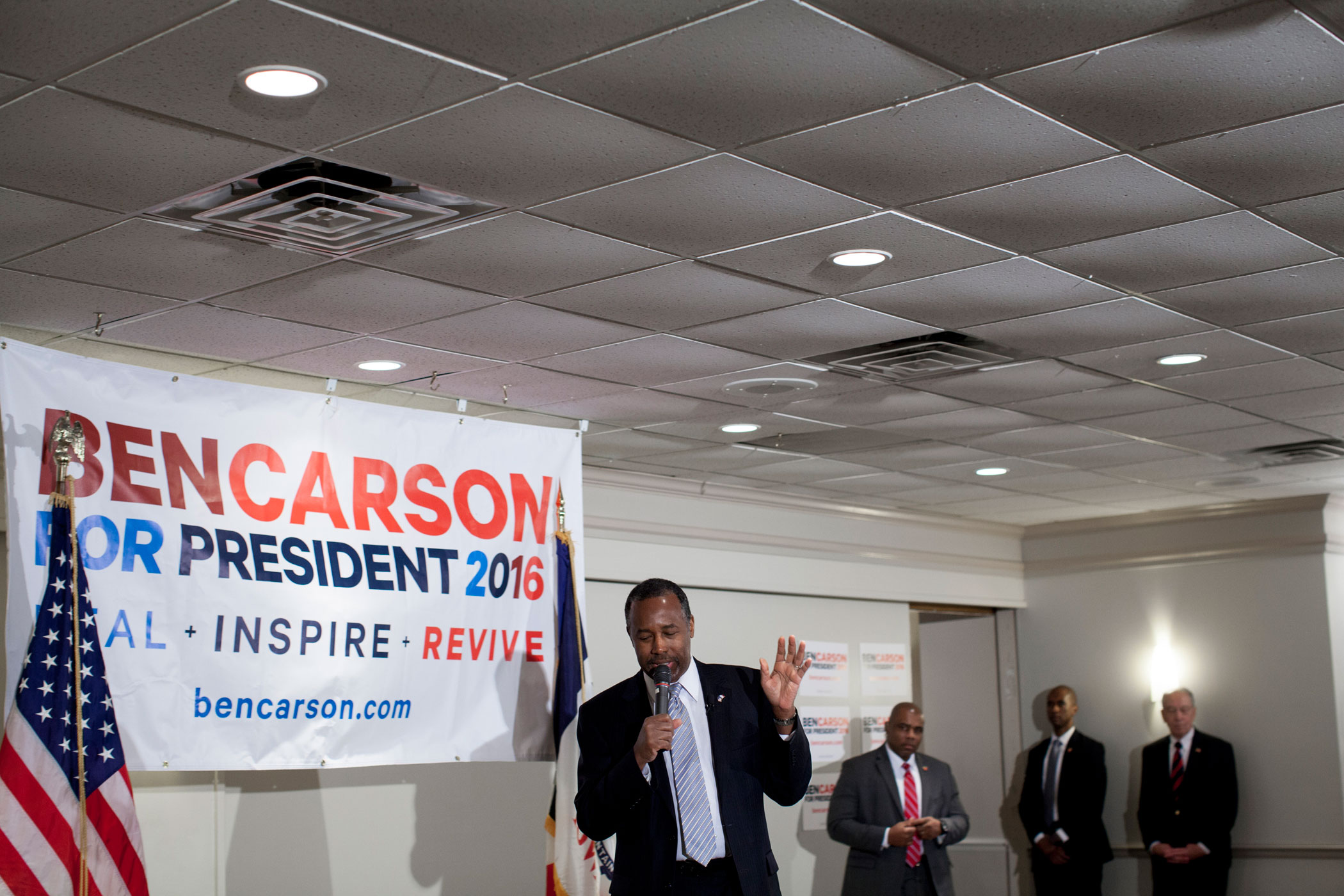

There’s a long held rule in American politics that devout candidates attract religious voters. But this cycle, there’s a different pattern nationwide: religious voters are embracing Donald Trump even though he is widely seen as the least religious presidential candidate. A new Pew report finds that only 5% of Republicans view Trump as very religious–that’s a big difference from 47% for Ben Carson, 30% for Ted Cruz and 20% for Marco Rubio. But Trump ties with Carson for the highest share of white evangelicals who say he would be a great or good president.

Read More: Why Trump is Winning Over Christian Conservatives

Does it differ between the Democratic and Republican caucuses?

While white evangelicals tend to be Republican, black Protestants and religiously unaffiliated voters are longtime Democratic constituencies. Half of religiously unaffiliated voters say Bernie Sanders would make a good or great president, while most black Protestants say the same of Hillary Clinton, according to Pew. One interesting addition is that Clinton is widely seen as a less religious person than when she ran for president in 2007. Then, 24% of adults said she was not religious—now 43% do.

Read More: Religious Voters Embrace Donald Trump Even If He Lacks Faith, Poll Says

With Philip Elliott, Elizabeth Dias, Alex Altman, Haley Sweetland Edwards, Jay Newton-Small, Zeke J. Miller and Daniel White.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com