It’s easy to think dangerous mosquito-borne diseases–the kind that can cause birth defects, severe illness or even death–are something only poor, tropical countries need to fear. Yet malaria, brought to the U.S. by European colonists and African slaves, wasn’t eliminated from the hot and humid American South until federal efforts finally eradicated it during World War II. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the agency now charged with protecting the U.S. public against such scourges, grew out of that campaign. (That’s why it’s headquartered in Atlanta.) More recently, dengue, West Nile and chikungunya–all mosquito-borne viruses–have invaded the U.S., brought from abroad by travelers and aided by a warming climate that has become more hospitable to disease-carrying insects.

Now there’s a new infectious invader to fear: Zika. First discovered in Uganda in 1947, Zika–then confined to the equatorial belt in Africa and Asia and thought to cause little more than mild flulike symptoms–was an afterthought to disease experts. But at some recent point, perhaps during the 2014 World Cup held in Brazil, an infected traveler brought the virus to Latin America, where it has exploded, spreading to more than 20 countries and likely infecting hundreds of thousands of people. But the real worry is what the Zika virus seems to be doing to pregnant women. Since the first case of Zika in Brazil in May 2015, the country has reported some 4,000 cases of microcephaly–a severe birth defect that causes a shrunken head and major brain damage. In 2014 the country of 200 million reported just 150 cases of the abnormality. Scientists suspect that Zika infections in pregnancy may be causing microcephaly and possibly other less visible forms of brain damage in infants. The CDC has warned pregnant women not to travel to affected countries in Latin America–a recommendation that may soon include the entire region. To reduce the risks from Zika, desperate governments in countries like El Salvador have gone so far as to urge women to avoid becoming pregnant until 2018–the epidemiological equivalent of a Hail Mary pass.

So far, there have been a handful of Zika cases recorded in the U.S., all in travelers who got sick elsewhere and brought the disease home. That means that for now, Zika probably isn’t actively spreading in the U.S. But the World Health Organization has predicted that the disease will eventually reach every country in the Americas except Canada and Chile–the only two where the Aedes mosquito, which carries the virus, isn’t found.

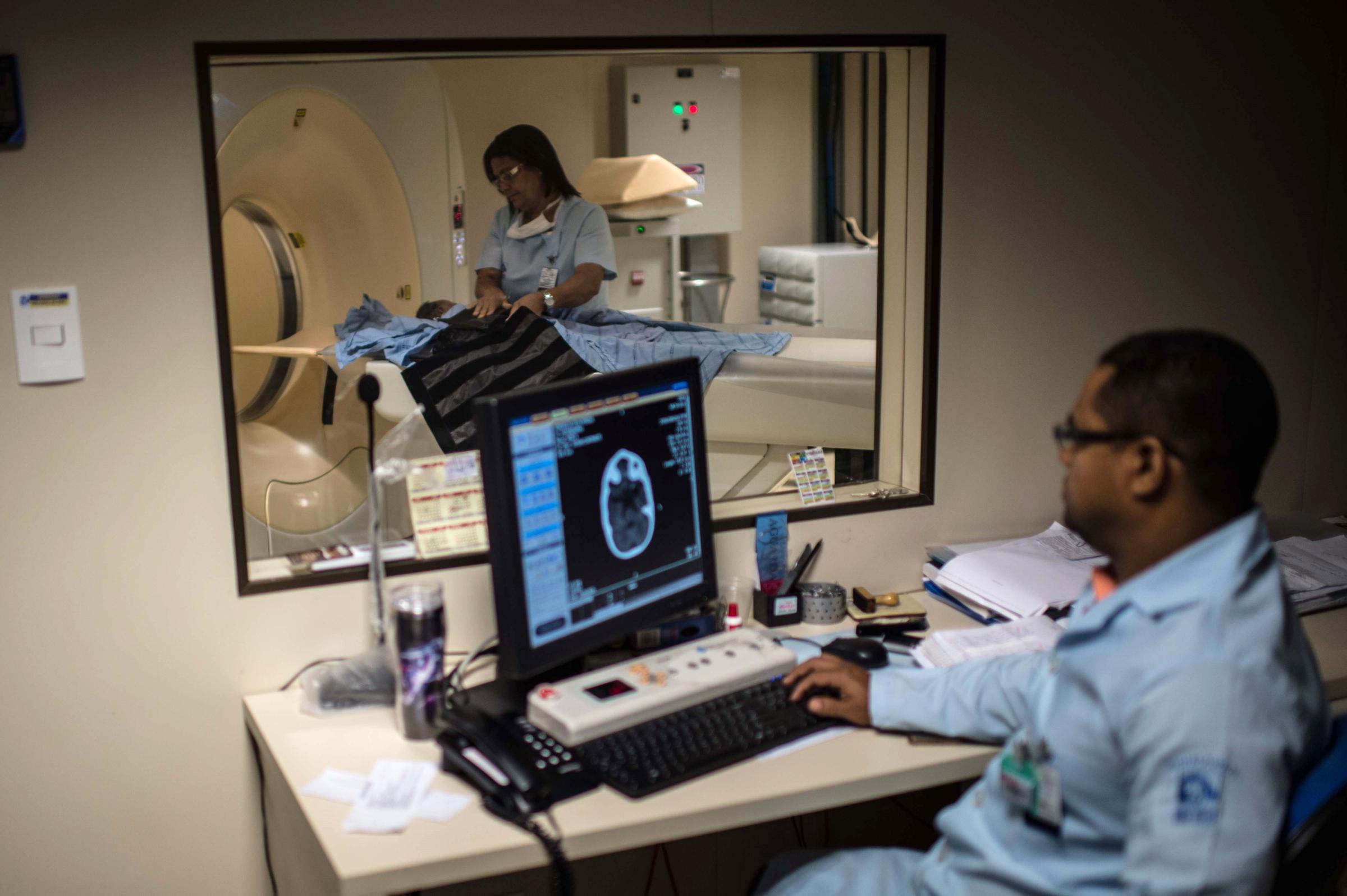

See the Impact of Zika in Brazil

“Things like this tend not to go away,” says Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is working on a Zika vaccine. “Cases may go up and go down, but it’s not just going to go away.”

Like other infectious diseases that have threatened the U.S.–malaria in years past or Ebola, for that matter–Zika is a reminder of just how connected we all are today, when there’s hardly a spot on the planet, no matter how remote, that’s more than 24 hours from a major city.

In a globalized world, we’re only as strong as the weakest health link. Even if the U.S. is able to control Zika within its own borders, as it did malaria, the out-of-control spread in the rest of the region will pose a constant danger, especially with hard-hit Brazil hosting the Olympics this summer. There are no walls that can keep out disease.

Zika diagnoses must be confirmed by lab tests, and the fact that 4 out of 5 people infected with Zika never show symptoms makes the virus hard to track and stop. The sudden explosion of cases–and the virus’ seemingly new ability to cross the placental barrier between mother and fetus–suggests that it may have mutated, which presents another challenge for scientists. Viral threats don’t stand still. They change and evolve.

And so does the planet we live on. Humans may not like a warmer climate, but disease-carrying mosquitoes do. They bite more and fly farther, and the viruses they carry tend to replicate faster. So as public-health officials prepare for a new onslaught of insect-borne disease, a new reality is setting in: In a warmer, connected world, Zika isn’t an epidemic. It’s a fact of life.

–With reporting by ALEXANDRA SIFFERLIN/NEW YORK

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com