Government officials in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and El Salvador are advising women to avoid getting pregnant, for fear that the fast-spreading Zika virus may cause severe brain defects in unborn children.

One question: how?

Read More: All the Way Humans Try to Kill Mosquitos—and Why We’re Still Losing

With more than a million people infected with the Zika virus in Brazil and millions more cases expected throughout the Americas, government health ministers say the best way to avoid the worst effects of the virus is for women to stop getting pregnant. Pregnant women affected with the Zika virus have given birth to thousands of babies with microcephaly, a rare birth defect that causes serious brain damage and lifelong impairment. But with strict abortion laws in place across most of the region and a massive unmet need for contraception and sex education, avoiding pregnancy in the affected countries may be easier said than done.

In all of Central and South America, there are only three countries where abortion is broadly legal (those countries are Uruguay, Guyana, and French Guiana.) Everywhere else in the region, abortion is only allowed in cases of rape or incest or if the life of the mother is at risk, depending on the country. Only Mexico, Colombia, and Panama allow mothers to terminate pregnancies because of a fetal impairment.

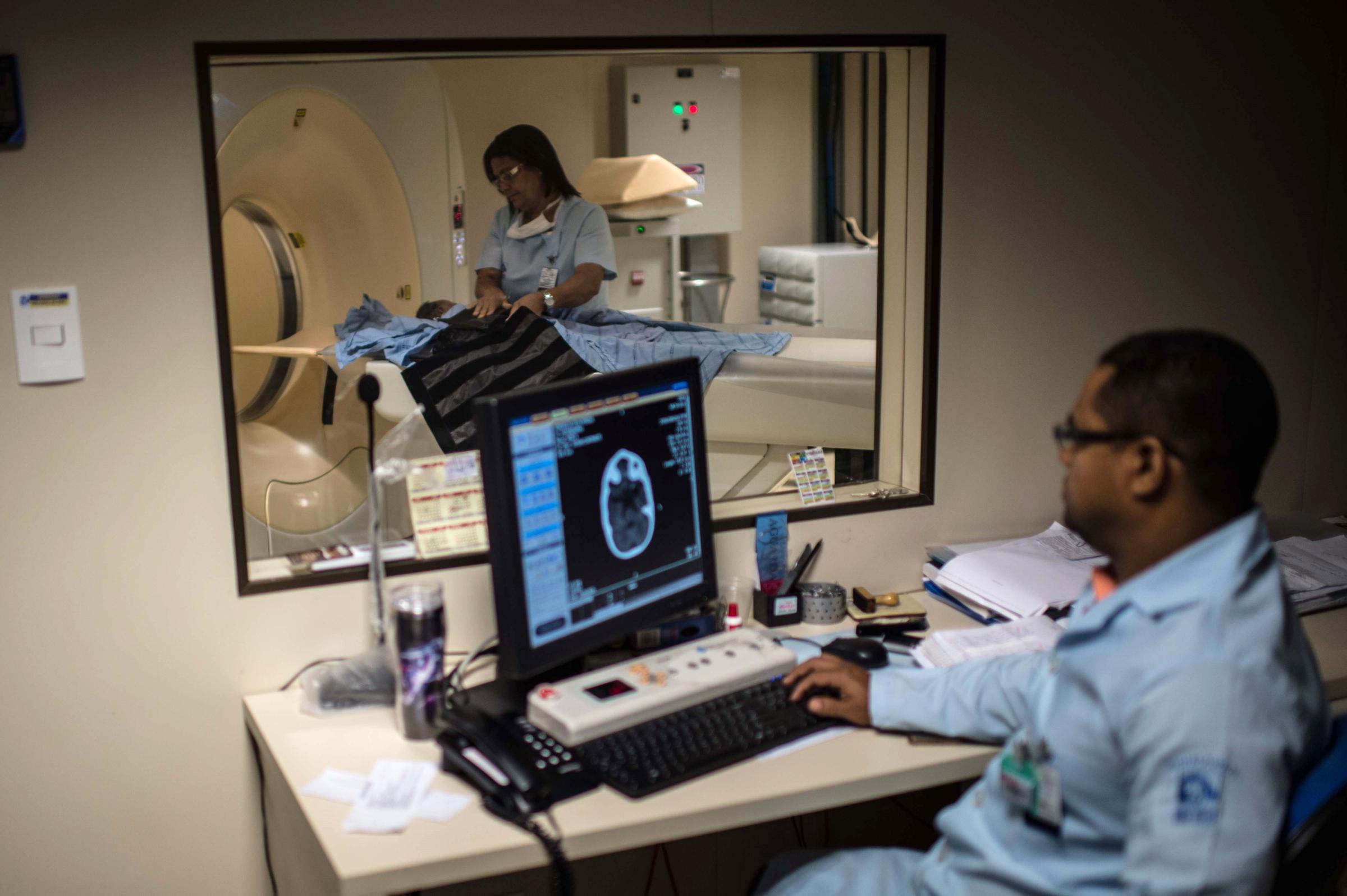

See the Impact of Zika in Brazil

Read More: CDC Says 31 Americans Diagnosed with Zika

And some countries, like El Salvador, forbid abortion in all cases, even when the mother has been raped or her life is at stake. Despite the public health recommendations to avoid pregnancy, deputy health minister Eduardo Espinoza told Buzzfeed News that the government will have to uphold the anti-abortion laws, “whether we like it or not,” but noted the public health crisis may trigger a debate that could revise the law. But experts seem skeptical that the anti-abortion laws, which have been repeatedly passed by mostly-male governments in Catholic countries, will be changed any time soon.

Human rights organizations condemned the government recommendations to avoid getting pregnant, saying that it’s unfair for poor women to have to assume such an enormous public health responsibility in the face of laws that make it impossible for them to do so. “You’re asking women to make a choice that sounds logical from a health perspective, but it’s not a real choice,” says Tarah Demant, senior director of the Identity and Discrimination Unit at Amnesty International. “It’s putting women in an impossible place, by asking them to put the sole responsibility of public health on their shoulders by not getting pregnant, when over half don’t have that choice.”

Even for women who aren’t already pregnant, contraception is hard to come by in these countries. According to the World Health Organization, 18% of births in Latin America are to teenage mothers, and Amnesty International estimates that more than 50% of the pregnancies in the region are unplanned. “They don’t have access to information, they don’t have access to contraception, and they don’t have access to the option to terminate a pregnancy,” Demant says, noting that contraceptive use among Latin American women is among the lowest in the world, and that emergency contraception is often expensive and difficult to access, if not illegal.

Read More: We’ve Neglected Diseases Like the Zika Virus for Too Long

Paula Avila-Guillen, a Colombia-based programs specialist for the Center for Reproductive Rights, called the recommendations “naive” and “irresponsible.” “The government is not issuing any recommendation for the men to use condoms, which is very unfair,” she said. “That makes the women responsible for everything.”

Even if women attempt to follow the recommendations through abstinence, sexual violence is so pervasive throughout the region that many women may get pregnant against their will. And most available data on contraceptive use only surveys married women or women in domestic partnerships, young adolescent girls and rape victims are often not counted, which means the problem could be even bigger than anyone thinks, says Amanda Klasing, a senior women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. Klasing says that even without reliable data on the unmet need for contraception throughout the region, it’s fair to say that “millions of millions” of women need birth control but don’t have it.

“When you aggregate all the barriers together, you’re looking at a large number of women and girls who really don’t have control over whether they become pregnant,” says Klasing. “The recommendations are really not something women can actually follow, even if they want to.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com