In a city known for iconic buildings, Thompson’s Restaurant was unremarkable. Located a few blocks from the White House, it sat on a commercial corridor: banks, storefronts, streetcar tracks. Inside, it was the kind of place where customers stood in line with their trays, grabbed a slice of cake, and sat down at a table. If they were white, that is.

Mary Church Terrell, an 86-year-old charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, was not white. Born in 1863, the year of the Emancipation Proclamation, she was the daughter of former slaves. She was also an 1884 graduate of Oberlin College, a suffragist, and a veteran activist for civil rights. On January 27, 1950, she had lived in Washington, D.C. for sixty years.

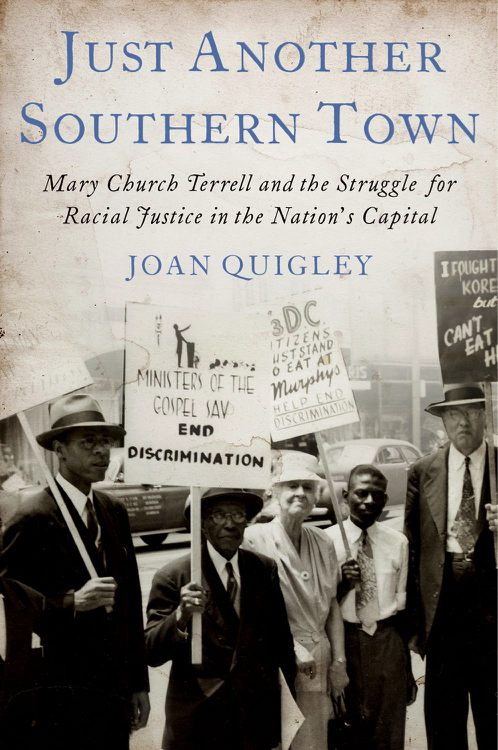

At roughly 2:45 p.m., Terrell walked through Thompson’s double glass doors. With her were three hand-picked compatriots: Geneva Brown and the Rev. William H. Jernagin, who were African American activists, and David H. Scull, a white Quaker. Collectively, none of them made it to the dining area. The manager, Levin Ange, stepped in front of Jernagin and refused to serve him because he was “colored.”

Elsewhere in Washington, President Harry S. Truman was leading a worldwide crusade for democracy. The manager of Thompson’s, however, was invoking the decades-old logic of Jim Crow, with its architecture of racial inferiority. That outlook, Terrell knew, was a liability in foreign affairs, especially when Washington restaurants refused to serve dark-skinned diplomatic envoys, treating them as if they were American blacks. She had no intention of backing down.

“Do you mean to tell me that you are not going to serve me?”

The manager apologized, saying it was not his fault; it was his company’s policy not to serve Negroes. Terrell, who had once considered training as an attorney, flipped into cross-examination. Was Washington in the United States? she asked the manager. Did the Constitution apply there?

“We don’t vote here,” replied Ange.

Though refused entry, Terrell had gotten what she came for. Thompson’s had violated Reconstruction-era ordinances barring Washington restaurants from discriminating by race. Now she could go to court. And by challenging Thompson’s in the capital, she could upend the edifice of separate-but-equal. That’s because the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld Louisiana’s segregated railway cars, used as a rationale congressional mandates requiring segregated Washington schools: if Congress, which had jurisdiction over Washington, could require segregated schools in the capital, Louisiana could segregate train passengers. Terrell had her cause and her fight.

When I first read about Mary Church Terrell and her battle against Thompson’s Restaurant, I wondered why they were not better known. She launched her test case against Thompson’s almost six years before Rosa Parks helped start the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott and a decade before sit-ins rocked lunch counters across the South. On June 8, 1953, three years after she had been refused service at Thompson’s, Terrell went on to win a unanimous decision from the U.S. Supreme Court. District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., Inc. invalidated Washington’s segregated restaurants a year before Brown v. Board of Education, the Court’s landmark school desegregation ruling in 1954. Yet Terrell and Thompson have been largely overlooked in the history of the civil rights movement, eclipsed by Brown and the unrest that followed, especially in the South.

It was no coincidence, however, that Thompson unfolded in the nation’s capital, with its tangled history on race, or that the Court used Thompson to relay a signal about the demise of separate-but-equal. Carved from the slaveholding states of Maryland and Virginia, Washington coexisted with the slave trade until 1850. Only on April 16, 1862, when President Abraham Lincoln emancipated Washington’s 3,100 slaves (nine months before the Emancipation Proclamation liberated them in the Confederacy) did the capital rid itself of slavery. Racial prejudice was another matter.

Still, Washington was not always a Jim Crow town. During Reconstruction, black men in Washington enjoyed full citizenship and voting rights, like white men. Beginning in 1869, the capital’s lawmakers enacted antidiscrimination laws, banning restaurants from discrimination based on race or color, ordinances that were still on the books when Terrell had tried to eat at Thompson’s. By 1878, though, as Reconstruction ended, Congress had dismantled Washington’s local representative government and stripped all residents – black and white – of voting rights. Washington became the equivalent of a federal possession, ruled by presidentially appointed commissioners.

Over time, the Reconstruction-era ordinances fell out of fashion and into disuse, especially after 1913, when President Woodrow Wilson’s administration segregated the federal workforce. In 1950, black and white Washingtonians had long gone to separate playgrounds, restaurants and movie theaters. With the NAACP mainly focused on school desegregation, the capital might have stayed that way.

But it didn’t, because of Mary Church Terrell. What she started inside Thompson’s on January 27, 1950 was a conflict more than a century in the making. It was a challenge to the central hypocrisy in American democracy: the clash between the nation’s professed belief in equality and its practice of subjugating blacks. As postwar activists like Terrell knew, that tension resonated in the nation’s capital, the symbolic headquarters of American democracy.

Terrell’s battle would engage the nation’s attention in the years ahead, when legal proceedings in the Supreme Court would alter the country profoundly. It was both a local affair—a particular cafeteria on a downtown Washington street refusing to serve an elderly black woman—and a national one, with repercussions outside the capital, across the South, and beyond. After World War II, Washington was not just another southern town; it had become the focus of the world.

Mary Church Terrell’s story had roots in slavery and spanned civil rights from the Emancipation Proclamation to Brown. Her case against Thompson’s helped usher in Brown and school integration, impelling a fractured Court to confront segregation at its threshold. An almost ninety-year-old African American woman had brought change to the nation’s capital, and it was irreversible.

Adapted from Just Another Southern Town: Mary Church Terrell and the Struggle for Racial Justice in the Nation’s Capital by Joan Quigley with permission from Oxford University Press USA. Copyright © Oxford University Press, 2016 and published by Oxford University Press USA. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com