As a girl, playing Barbies with my sister was a favorite activity—dressing them, undressing them, popping off their heads, snickering at our father cursing loudly as he walked barefoot in the basement across a sea of sharp, skinny naked limbs and equally sharp, pointy naked breasts. We had dozens of Barbies, almost all of them smooth peach plastic and blond-haired, enormous bosoms perched atop teeny waists, toes perpetually en pointe. The only woman I had ever seen who looked like Barbie was Vanna White on Wheel of Fortune—another silent blonde floating on the balls of her feet.

But the Barbie of my childhood just got an extreme makeover. The top-heavy blond version is now flanked by a diverse cast of friends also named Barbie. There’s a short one, a tall one and one whose curves aren’t only on her chest. There’s a wider palette of skin tones, and an assortment of hairstyles and textures. Market pressures, perhaps bending to societal ones, have forced Mattel to finally make Barbie look a little more like American women. It’s a feminist victory, especially for parents who want to allow their kids the creative fun of playing with dolls but don’t want to send the message that looking like Barbie is something to which girls should aspire. For girls, the world has been changing for the better, and Barbie is trying to catch up. In her defense, it’s hard to move fast in heels.

One pointy-toed step forward, though, is hardly a giant leap for womankind. Barbie is a literally objectified woman, not a superhero or an action figure but a plastic lady notable because she’s pretty. And she remains a quintessential “girls’ toy,” Patient Zero in the pinkification pandemic that has infected toy stores for two generations and now prominently segregates “girls’ toys” (Dolls, Arts & Crafts and Bath, Beauty & Accessories on ToysRUs.com, for example) from “boys’ toys” (Action Figures, Video Games, Bikes & Ride-ons).

Read about Barbie’s new body here

New Barbie is one data point in an improving landscape for girls: Target made strides by desegregating its toy aisles, and as far as Disney princesses go, Frozen’s Elsa is pretty progressive. But even as the toy industry loses market share to screens, girl-centric movies may not be as girl-friendly as they appear: according to a new study, the females in Frozen get only 41% of the speaking time in their own story.

When girls are trapped in the pink box—or minimized in dialogue—their interests are reined in, their physical and psychological development stymied. Yet girls are fed a steady diet of princesses, makeup and homemaking (Toys “R” Us suggests the Just Like Home Dyson Ball vacuum cleaner as a “toy” for girls ages 5 to 7).

1. Executive ‘Career Girl’ Barbie, 1963

Outfitted in a tweed skirt suit and gloves, Barbie had her first stint as a corporate exec in 1963 — a time when women were almost entirely absent from top-level roles in companies and were making 59 cents on the dollar compared to men. She must’ve liked the job, considering that she’s taken it up three more times since, with the latest Business Executive Barbie released in 1999.

2. Astronaut Barbie, 1965

Barbie’s first space voyage in 1965 took her to the moon a full four years before Neil Armstrong, and over a decade ahead of Sally Ride, the first American woman in space. She has since made two more missions and has even taken her talents to Space Camp to educate the next generation in a partnership with the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Ala..

3. UNICEF Ambassador Barbie, 1989

Taking a page from Audrey Hepburn, who served as a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF from 1989 until her death in 1993, Barbie became one herself in 1989. The undertaking rounded out a decade of diversity in her career, including stints as an aerobics instructor, a rock star, and an officer in the U.S. Army.

4. Rap Musician Barbie, 1992

Barbie first became a singer in 1961, but her musical talents have since expanded. In 1992, she made her rap debut as “Rappin’ Rockin’ Barbie” with her boom box in tow, and shared her street cred with the world in a memorable commercial. Unfortunately, this is one career she hasn’t since revisited.

5. Marine Corps Sergeant Barbie, 1992

Barbie made history in 1989 when she first joined the military as an officer in the U.S. Army, but to date her 1992 position as a sergeant in the Marine Corps is the highest rank she’s held in the Armed Forces. As a sergeant, Barbie would’ve had a great deal of responsibility directing eight soldiers in combat operations as their squad leader.

6. Presidential Candidate Barbie, 1992

Long before Hillary Clinton hit the campaign trail, Barbie made her first bid for President, joining the fictional ’92 race. No word on how she fared in her first election, but she has since made four more bids for the Oval Office—the latest of which was in 2012.

7. Paleontologist Barbie, 1997

So nice she did it twice! Barbie followed up her first foray into paleontology in 1997 with another in 2012. Both times she proved that she wasn’t afraid to get her hands (or her signature pink flair) dirty working with dinosaur fossils.

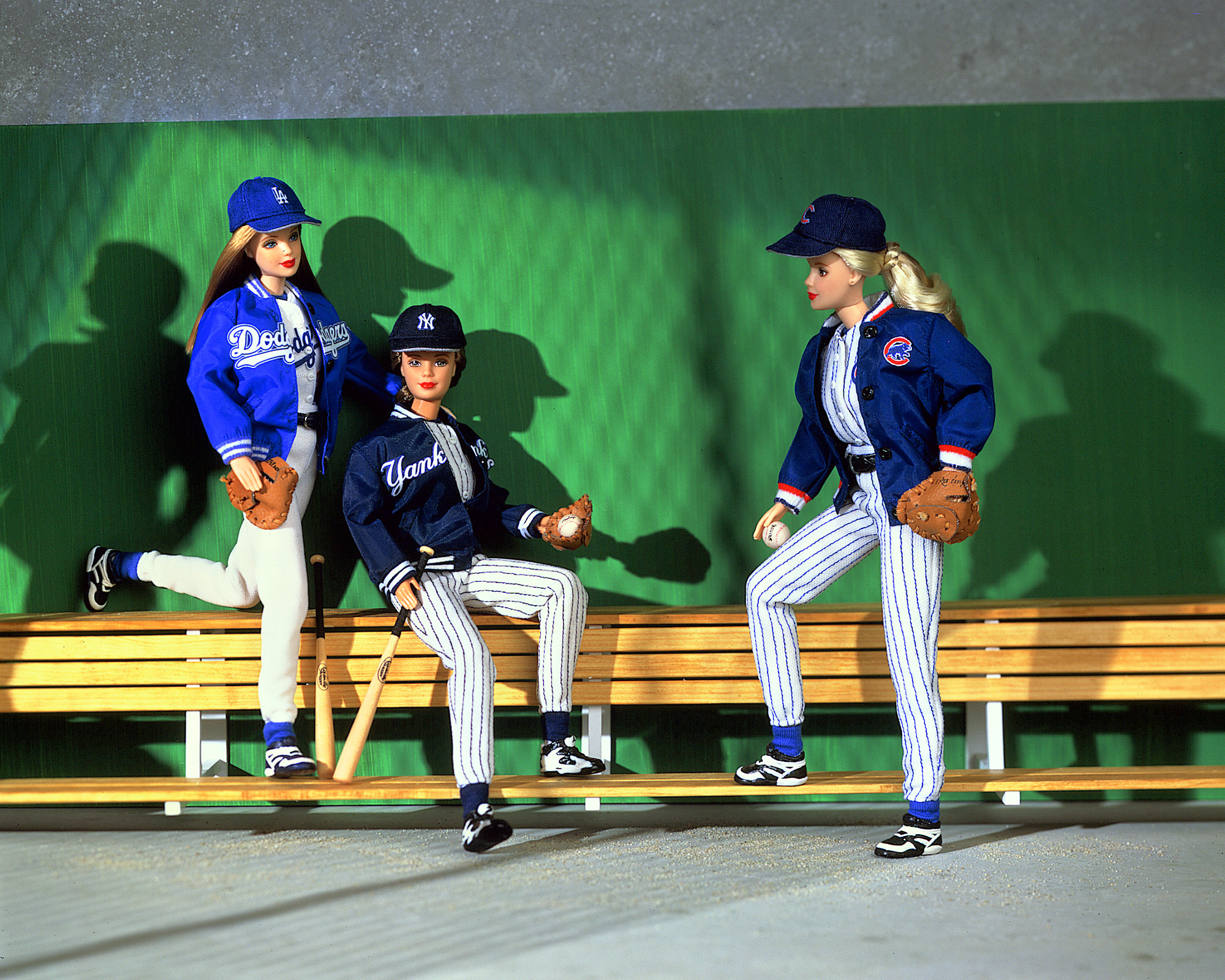

8. Major League Baseball Player Barbie, 1998

To date there has never been a woman in the MLB (though that could be changing soon), but Barbie is always a step ahead of the game. In 1998 she made her MLB debut, with different editions for the New York Yankees, Chicago Cubs and Los Angeles Dodgers. That same year the Yankees won the World Series—surely thanks in part to the help of their newest teammate.

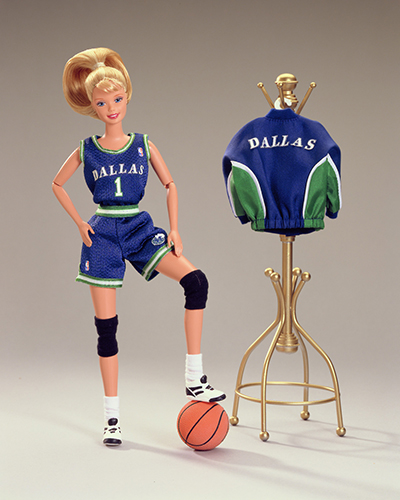

9. WNBA Player Barbie, 1998

Barbie added “baller” to her resume in 1998 when she joined the WNBA as No. 1 at a fictional Dallas team, though this was far from her first stint in sports. She made her Olympic debut in 1975, and throughout her long career she’s sampled everything from Olympic gymnastics (1996) to World Cup soccer (1999).

10. American Idol Winner Barbie, 2005

American Idol introduced the world to Carrie Underwood when she took home the title in 2005, but Barbie took it upon herself to rewrite history when a version of the doll was unveiled as an American Idol competitor the same year. With Britney Spears’ hit “Oops! … I Did It Again” as her audition song, she squared off against friends Tori and Simone for the top spot, with more than 700,000 fans voting for a winner on the company’s website. No word on what Randy, Paula and Simon thought of her performance, though.

11. SeaWorld Trainer Barbie, 2009

Back when Barbie first joined the team at SeaWorld it was still a tourist favorite, but following the release of the explosive documentary Blackfish in 2013, the park is no longer beloved by the public, or Barbie herself for that matter. In April 2015 ,Mattel was lauded by animal rights groups for ending the production of its SeaWorld Trainer dolls.

12. Computer Engineer Barbie, 2010

In 2010, Barbie wanted a hot tech job, but she found herself in hot water instead when a companion book entitled Barbie: I Can Be A Computer Engineer went viral a few years later, with critics saying that it was sexist. Thought Barbie was described in the book as a computer engineer creating a new game, it turns out that she needs the help of two male colleagues, Steven and Brian, to actually make the final product. Backlash was severe, and Mattel apologized, pulling the book from shelves soon after.

13. Arctic Rescuer Barbie, 2012

Barbie was a long way from Malibu in her 2012 role as an arctic rescuer, but she made herself at home with a pink snowmobile and matching igloo for her pets.

There’s nothing wrong with caring or cleaning; there is something wrong with the overwhelming message that caring and cleaning are aspirational things for girls, often to the exclusion of exploration and invention. Boys, too, are getting that same memo: caring for a baby or the home is girly and, by extension, undesirable.

The new Barbie may reflect a feminist culture shift, but let’s not fool ourselves into thinking more diversity means Mattel has the best interests of your daughter at heart. The company was losing sales; it realizes that branding something as empowering is a great marketing tool; and it is likely to profit from the fact that four different Barbie bodies means four times the sets of clothing and accessories.

Barbie today may be more realistic looking than at any other point in her 57 years. But her changes are superficial, and Mattel is still very much thinking inside the pink box.

Filipovic is a lawyer and writer

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com