Correction appended, June 15, 2016

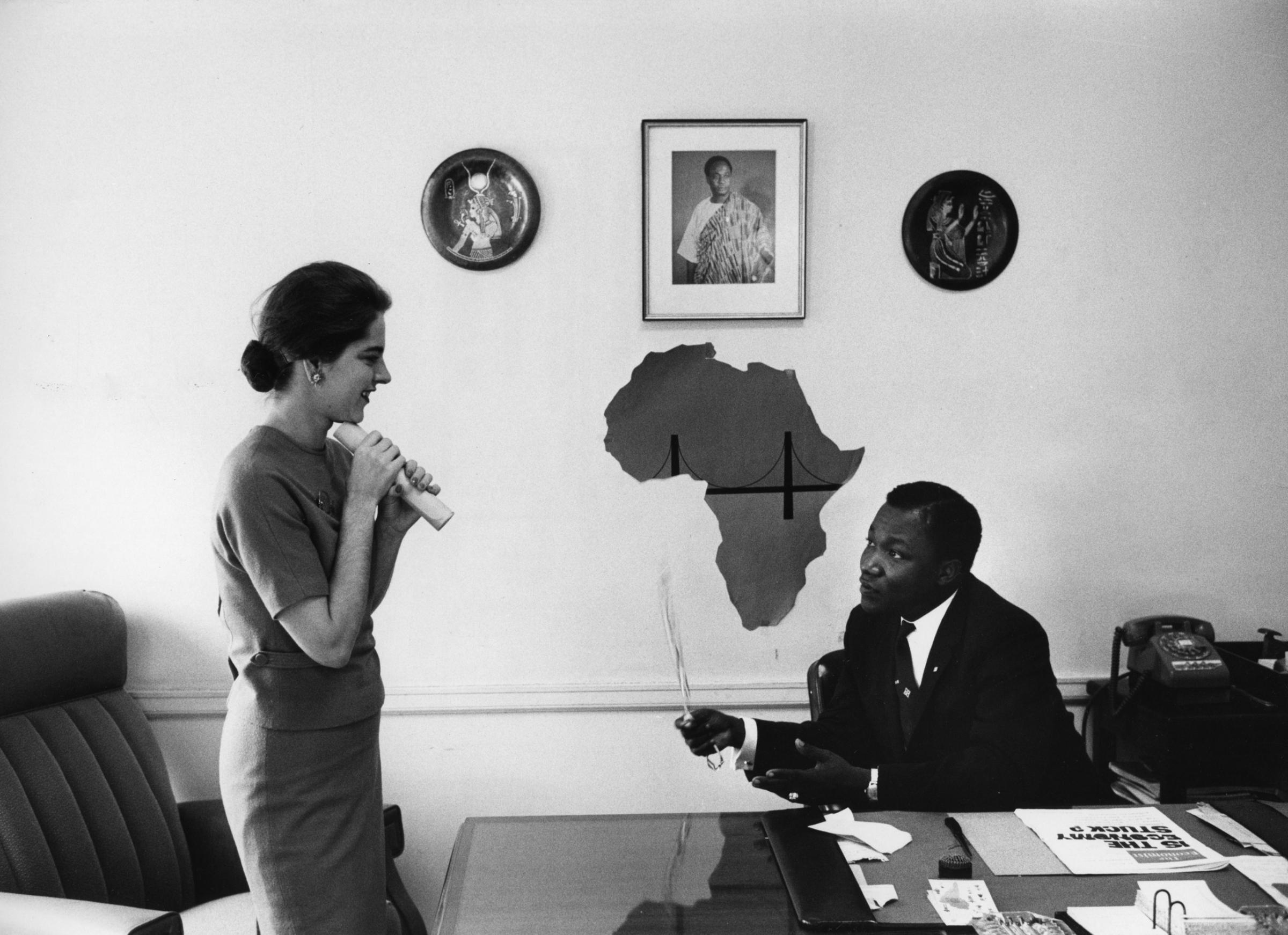

When Gayle Quisenberry arrived in Washington, D.C. in the early 1960s, she had already lived through a minor scandal: during her junior year at Goucher College, the Long Island native had moved to Lagos, Nigeria, under the auspices of the Experiment in International Living. As her daughter Leyla Sharabi tells TIME, “The whole social circle [her family] moved in—this was just not done. She was in the newspaper.”

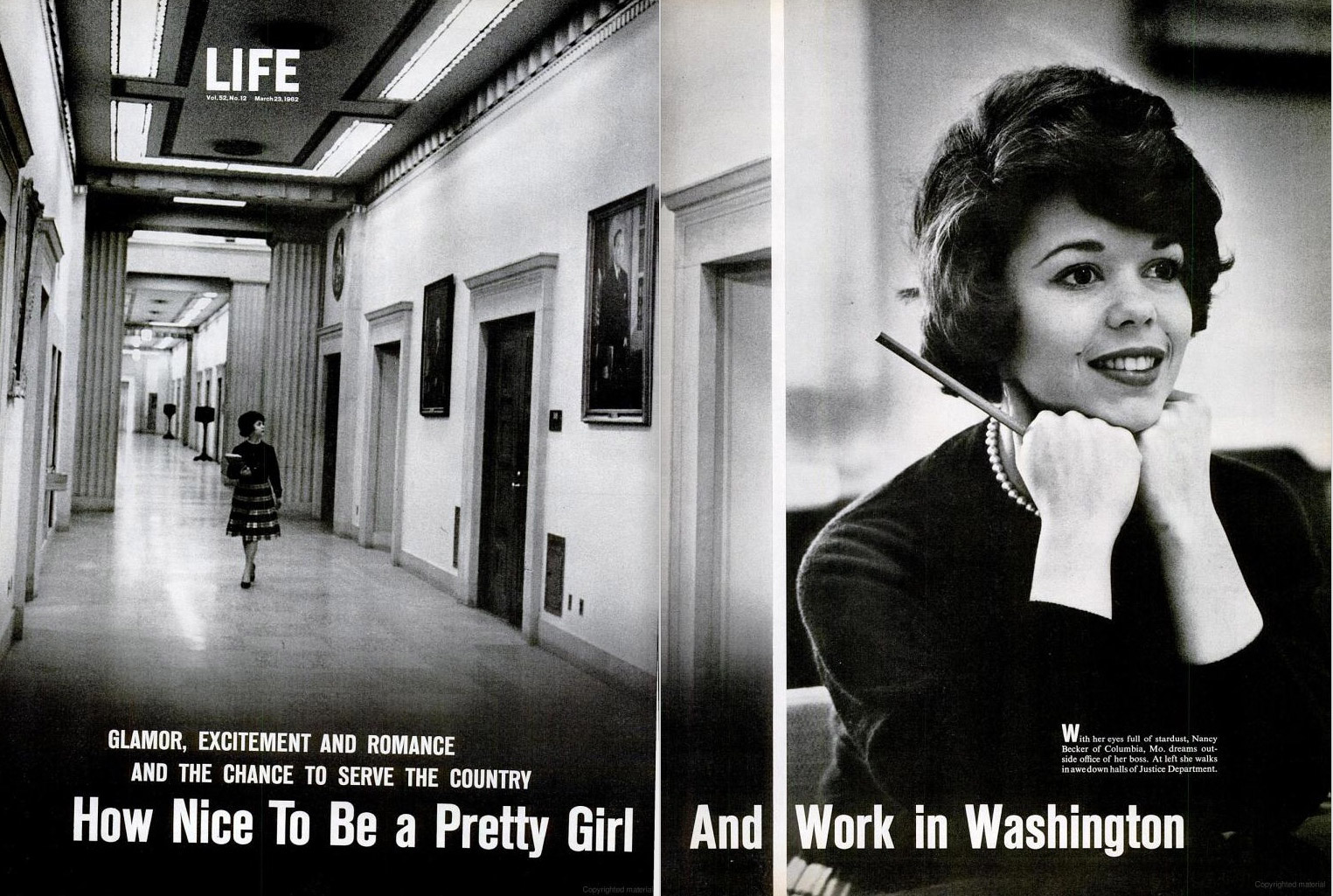

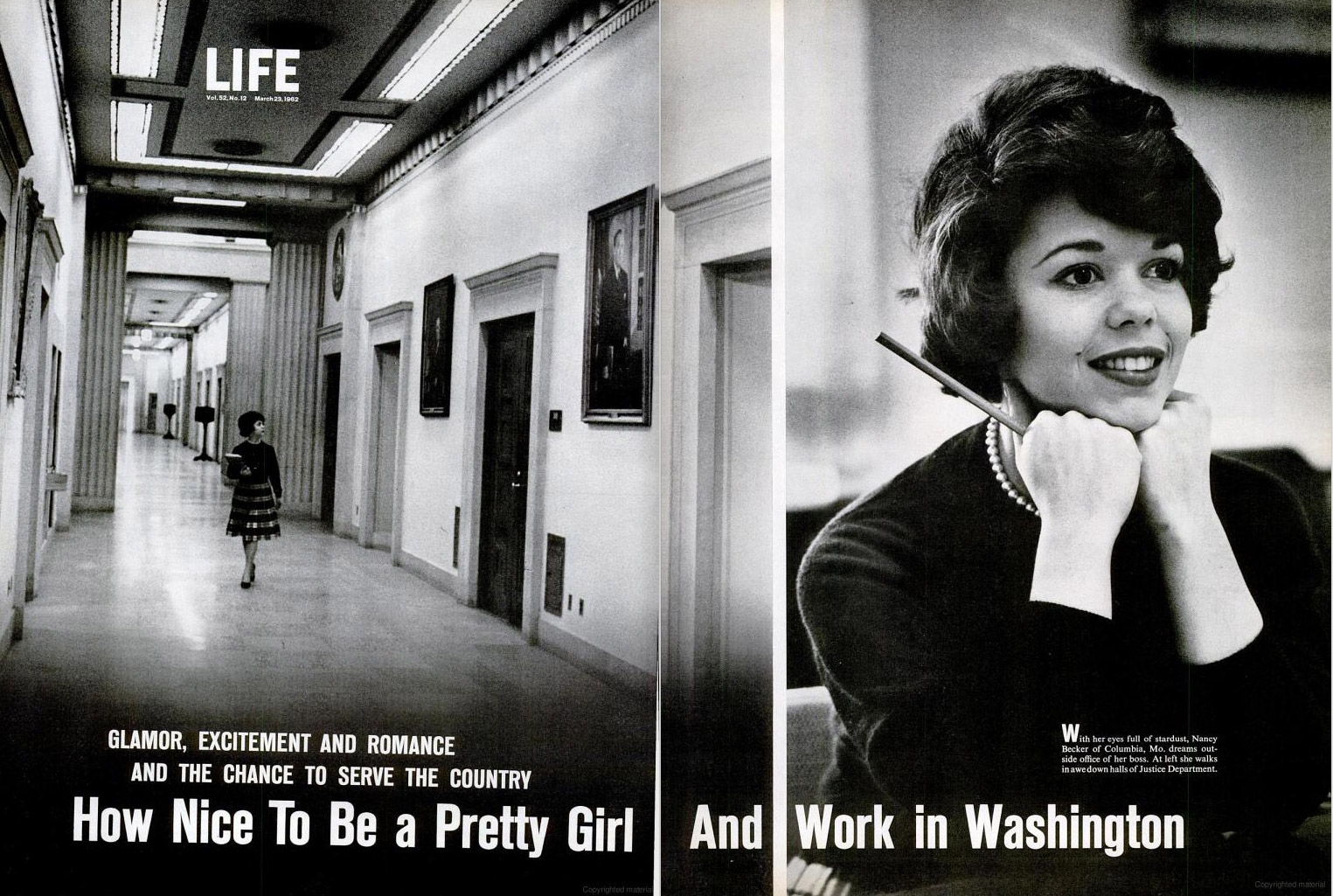

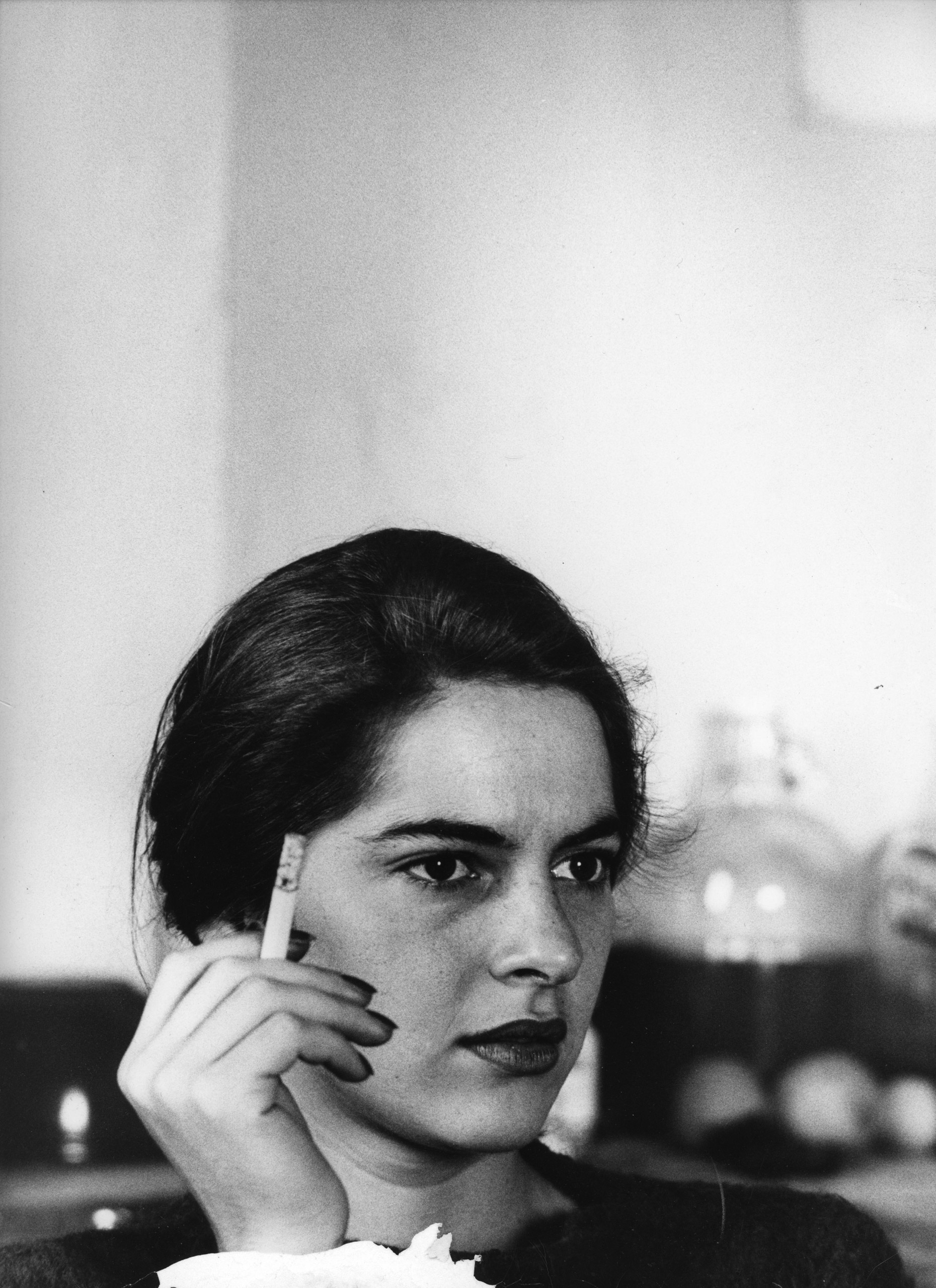

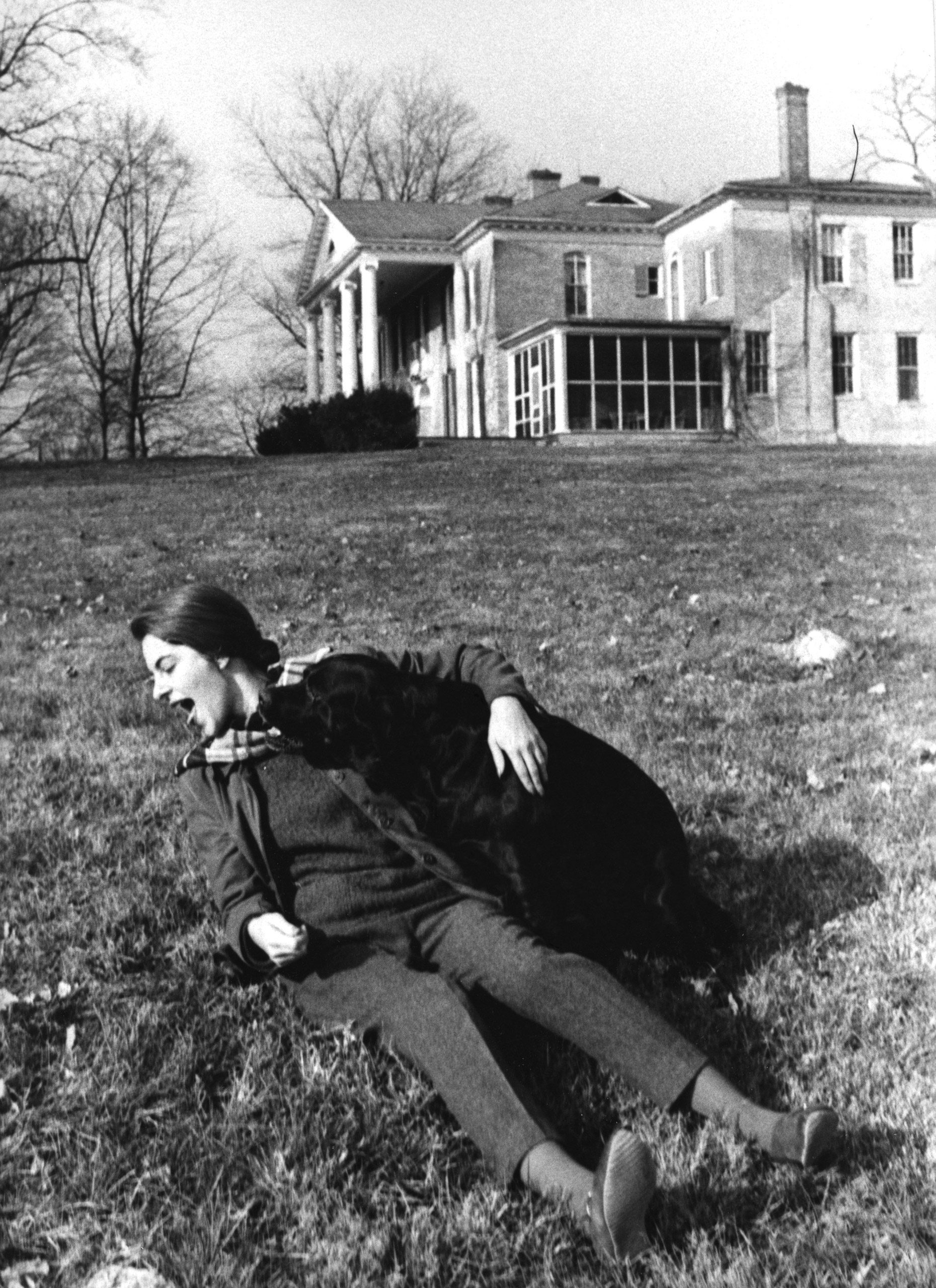

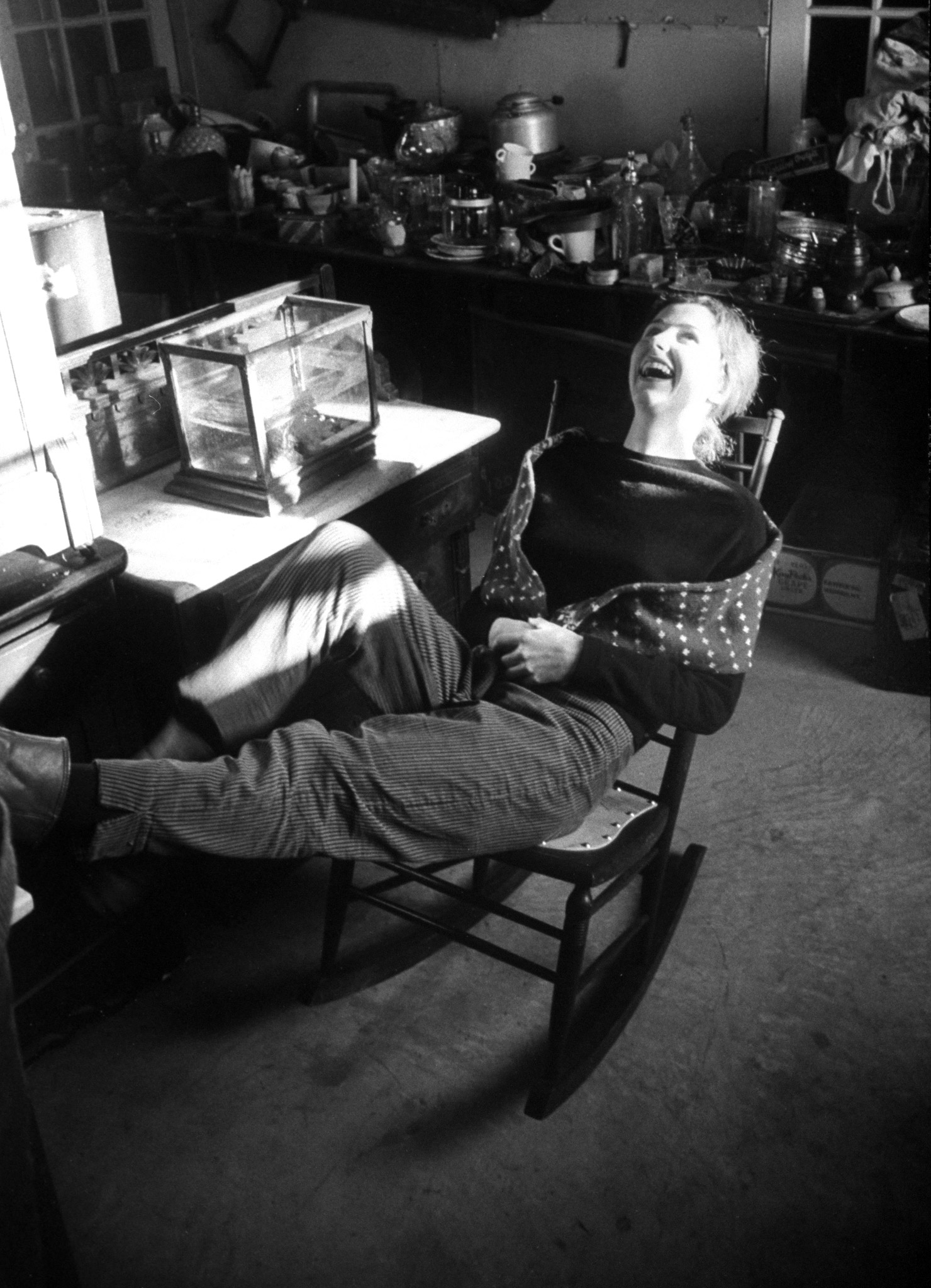

After returning from Nigeria to work for the humanitarian organization CARE in New York City and then moving on to D.C. to work for the monthly journal Africa Report, Quisenberry was one of several young women photographed by LIFE’s Art Rickerby for a 1962 story titled “How Nice To Be a Pretty Girl and Work in Washington.” Their place in the capital city wasn’t quite a scandal, but these women working with senators and diplomats were unusual enough to warrant a photo essay, with language that reads today as patronizing—their looks are mentioned as much as their brains—but which was, at the time, characterized by a sense of wonder at their decision to forgo settling down in favor of “glamor, excitement and romance.”

Recent conversations about women in Washington have tended to focus on a particular woman making history in our nation’s capital. And for the last eight years, Americans have had a First Lady who has made a point of bringing issues affecting women to the forefront, as she’s doing on Tuesday with the United State of Women summit. Back in the 1960s, the women making history in the city were, to the general public, largely nameless. They were a cohort that often lived and ate and socialized with one another. The young women held jobs ranging from lawyer to stenographer to, as in Quisenberry’s case, right-hand woman to one of the nation’s leading experts on Africa—who just so happened to also be a woman, a specialist named Helen Kitchen.

The LIFE story told of women with “eyes full of stardust,” drinking in their proximity to power and enjoying the favorable ratio of 1.8 men for every woman. After work they taught dance classes or played co-ed football, juggled dates or sorted placecards for fancy state dinners. For some of these women, this chapter would be short-lived. For Quisenberry, it would end after she married Hisham Sharabi, a Palestinian-American author, intellectual and professor, and had Leyla, her first and only child, at the relatively advanced age (for those times) of 32. “Even though she was a relative powerhouse by 1950s and ‘60s standards,” says the younger Sharabi, “by the time she was a mother, we were right back to the 1950s. She was a housewife.”

Still, the kind of woman who at 20 eschews all expectations placed upon her isn’t apt to let her life get boring. Sharabi confirms that her mother (who changed her name to Gayle Sharabi) wasn’t content to limit her tasks to her homemaking duties. She became an expert horticulturist, maintaining an impressive garden of native plants. Each morning, she left no page of the New York Times or the Washington Post unturned. Each night, she watched the evening news.

But as a woman of few words, Quisenberry rarely spoke of her working days to her daughter. “That’s the thing about moms,” says Sharabi. “Once they become moms to their children, they’re moms. I didn’t know about her life and her career.” As Rickerby’s photos of her had not actually been published in the LIFE photo essay, it wasn’t until after her mother died at 58 in 1995 that Sharabi came across his images of her, offering a glimpse of a young Washington woman at work.

The LIFE story didn’t quite have the language to describe the exploits of these career-oriented women. It often described them in terms of the way their presence affected those around them: “A pretty young girl for some reason,” it read, “seems to improve everyone’s mood.” But it did venture a prognostication about the generations to follow this group of “Washington girls” which, more than 50 years later, could well come true:

“One day,” the magazine said, “a woman will be President.”

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the type of plants that Quisenberry maintained. They were native plants.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com