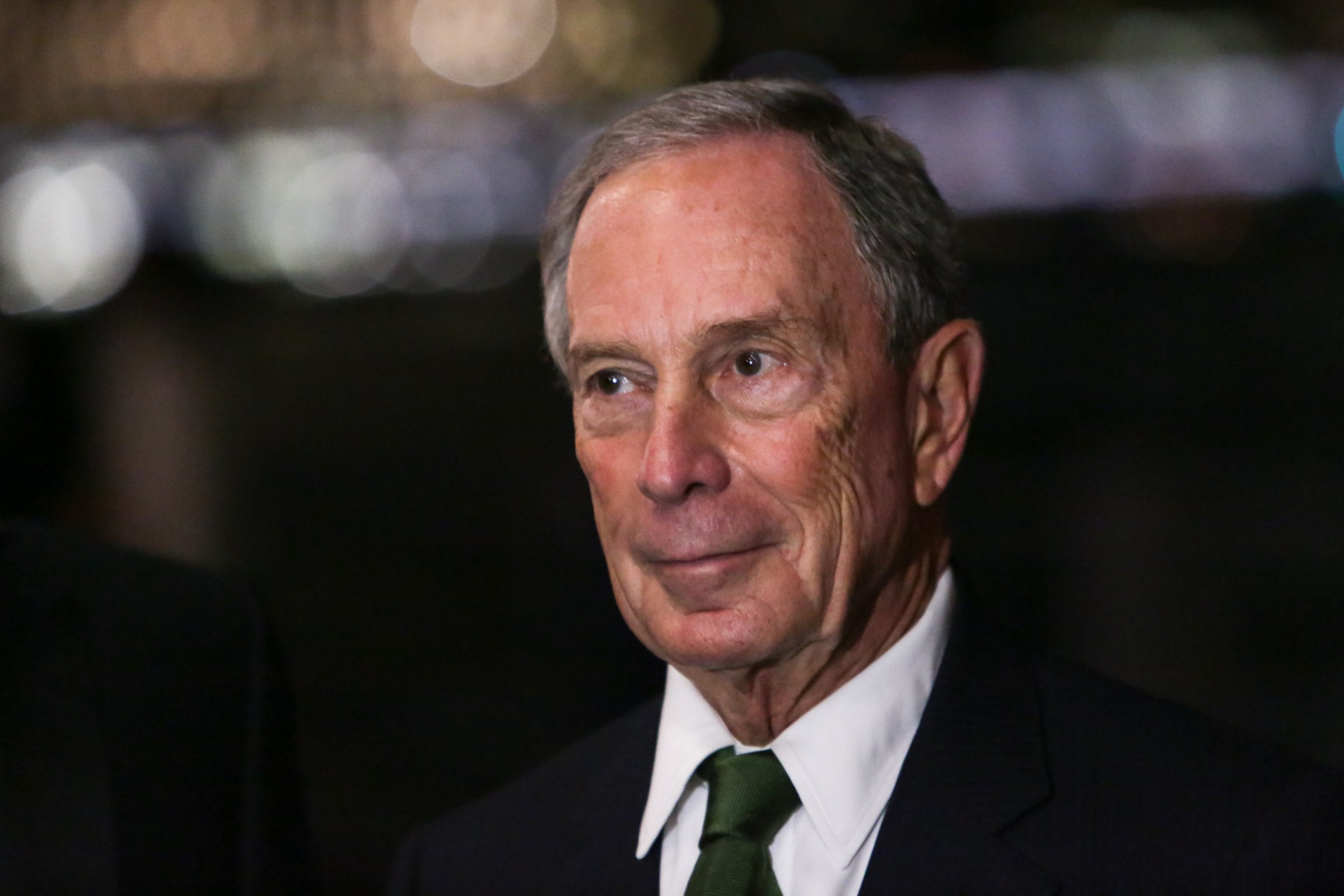

Last week Michael Bloomberg, former three-term mayor of New York City, told his advisers to inform the media that he is laying the groundwork for a possible presidential campaign as an independent. This is the third presidential cycle in which he has contemplated such a run. So bold, given the two-party tyranny that heavily controls the ballot choices of voters. It is not indecision that is rendering him tentative. No one who has built a booming media empire from a relatively small investment in the early 1980s, and who was elected as a Republican in a Democratic Party stronghold, can be charged with indecision.

Rather, the problem is a deeply researched hesitation. Bloomberg wants to run only if he thinks he can win. He is not interested in making collateral points or pursuing causes that are not directly on the path to electoral victory. In his typically methodical fashion, for nearly 10 years Bloomberg has been quietly conducting surveys and polls and having frank discussions with his advisers, colleagues, historians and electoral specialists over the variables.

He deeply believes he is the most capable candidate, and the constants are his assets. His wealth saves him precious personal time and conveys a widely appreciated impression that he cannot be bought. His company name makes his national name recognition a fairly easy task. He governed a fractious Democratic city in a hands-on, largely bipartisan manner—showcasing a New York value—that is sought by people tired of gridlock and rancor. He can talk about the needs of the tens of millions of urban dwellers more graphically than any of the present candidates.

Although he has received criticism for his positions on civil liberties and poverty policies, he panders less than almost any national politician. Just ask the tobacco and junk-food companies, the NRA and the restaurant industry (hold the soda and the smokes). Remarkably, he resisted heavy local pressure in 2010 and supported the right of an Islamic cultural center to locate in lower Manhattan. Then there are views and candidates he has championed that are disliked by many. He favors charter schools and as mayor was protective of Wall Street, minimizing its serious derelictions in favor of emphasizing its economic importance to New York City.

Bloomberg is right to worry more about the variables than these constants. His major concern is the vestigial Electoral College; he knows that Ross Perot, running an erratic campaign in 1992, still won 19 million votes without garnering one electoral vote. He worries about how swayable hereditary voters would be for an independent. In 2011, Bloomberg told me only half facetiously, “Fifteen percent of the Republicans would vote for Leon Trotsky if he were their party’s nominee, while 15% of the Democrats would vote for Ayn Rand if she was their party’s choice.” But this year’s elections are extraordinarily volatile. With a large number of independent voters looking for winners, and party loyalties fraying on everything from privacy protections to criminal-justice -reform and health care, all bets are off.

The biggest variable Bloomberg faces is whether the two parties will nominate candidates he considers to be polarizing figures representing the extremes of each party: Donald Trump—or worse, Ted Cruz—and Senator Bernie Sanders. And he is thinking that a robust three-way race could give him pluralities of popular votes (under a winner-takes-all system) in enough states to give him the 270 or more electoral votes needed to win.

The two parties could not keep Bloomberg out of the presidential debates since he would meet their arbitrary criterion of registering 15% or more in the polls. In theory, he could start getting on all state ballots if he announces by early March, according to Richard Winger of Ballot Access News.

But will we know by the end of March who the likeliest nominees are? For Bloomberg, since he is not satisfied with merely broadening the content and horizons of the 2016 presidential campaign, that may be the decisive variable for his decision. With his billion-dollar budget at the ready, he wants to become the known centrist candidate who can get results from legislators of both parties and does not scare the presently terrified party establishments.

I don’t believe in blanket endorsements. And viewing independent candidates as “spoilers” is to use a politically bigoted word, as if such challengers are second-class citizens. Everybody has a First Amendment right to run for office.

But if successful, Bloomberg would be the first independent presidential candidate ever to win the White House. Agree with his candidacy or not, that prospect alone could unleash forces, down to local elections, for a much needed competitive democracy.

Nader is the author of Unstoppable: The Emerging Left-Right Alliance to Dismantle the Corporate State and a four-time presidential candidate

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Behind the Scenes of The White Lotus Season Three

- How Trump 2.0 Is Already Sowing Confusion

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: All Those Presidential Pardons Give Mercy a Bad Name

Contact us at letters@time.com