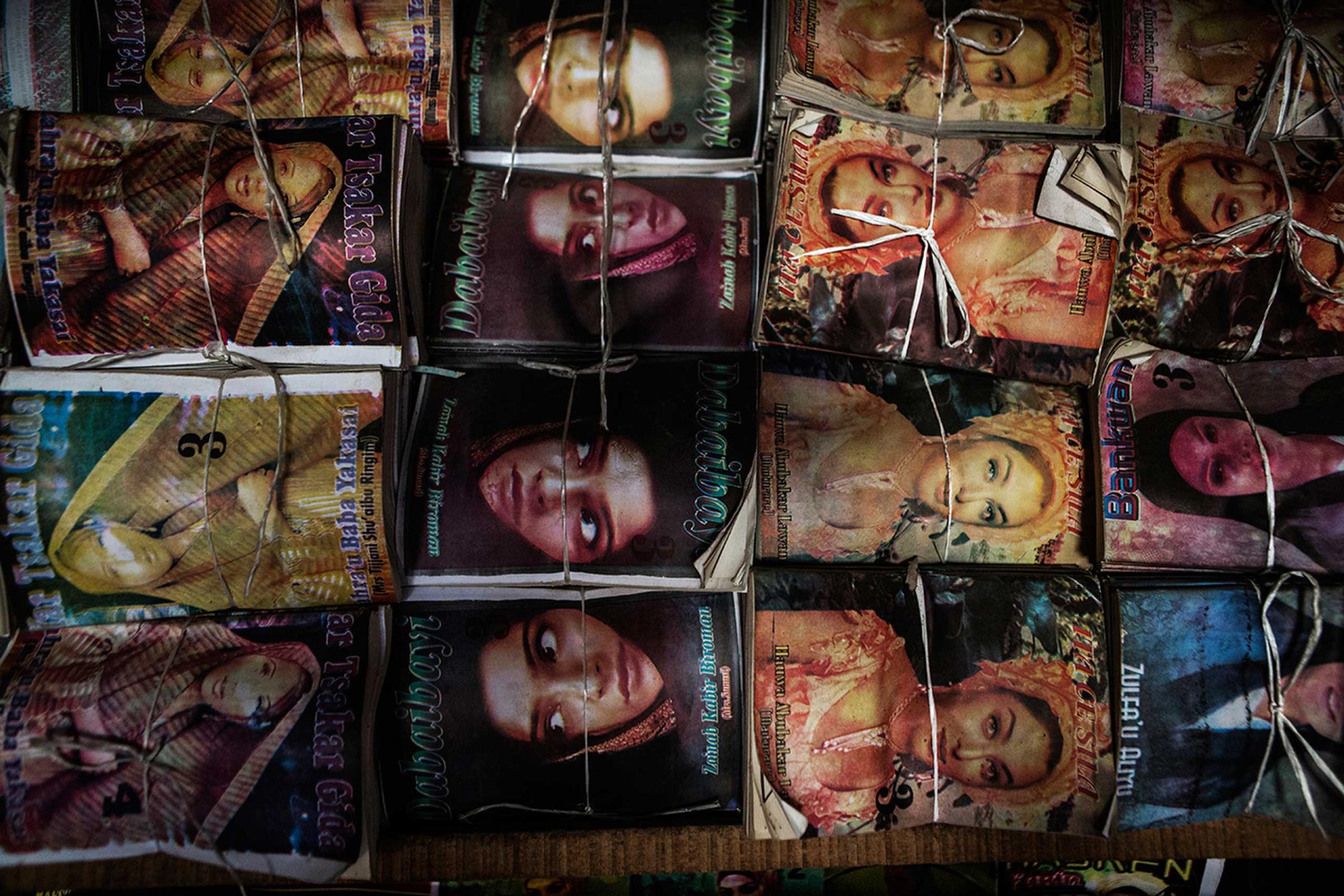

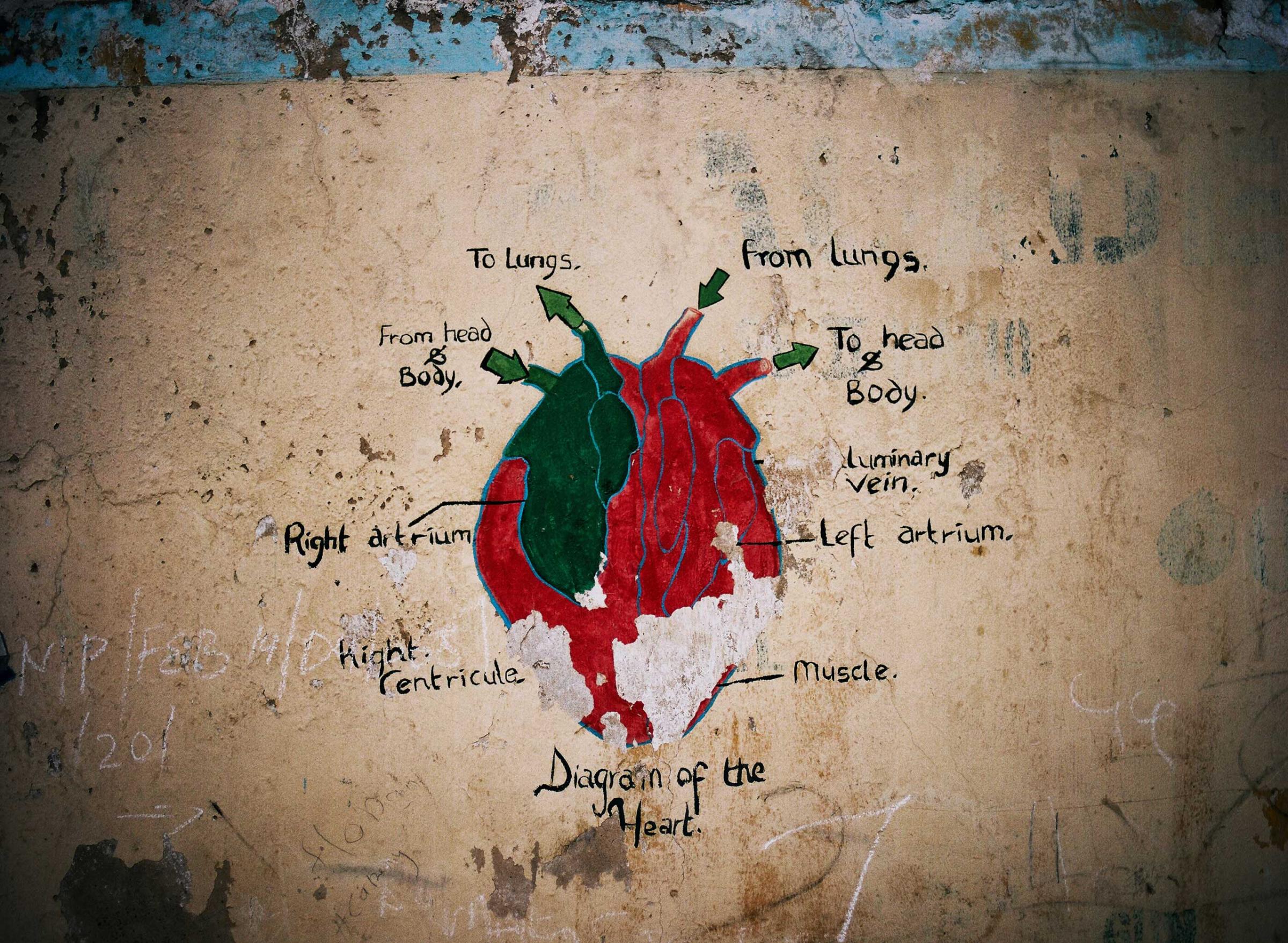

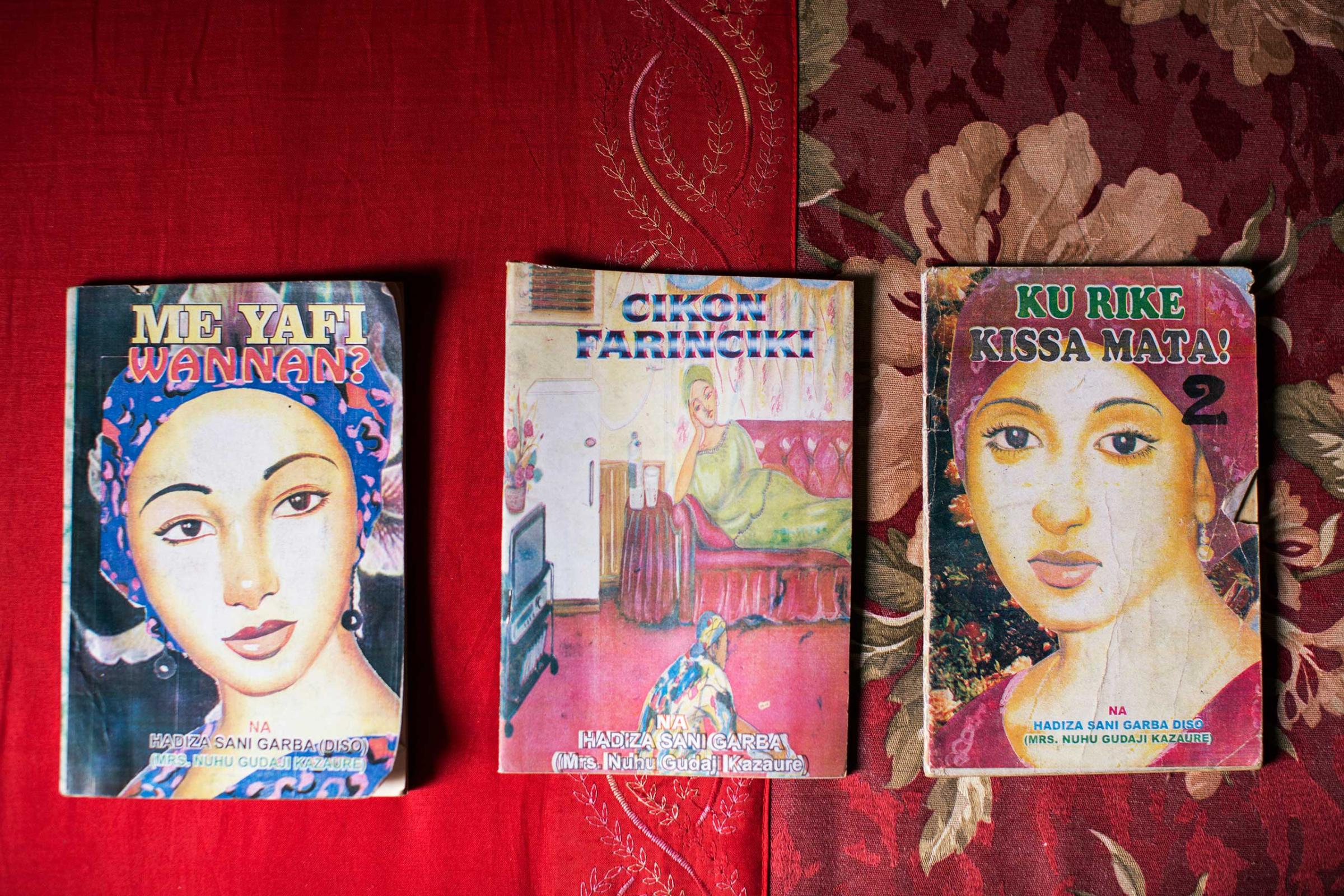

The first thing you notice about Glenna Gordon’s book Diagram of the Heart is that it’s small. Small enough to fit in a coat pocket. It has a soft cover too. It is a design that purposefully mimics that of northern Nigerian romance paperback novels. This is a book that eschews the norms of the Western photobook industry in order to celebrate the pioneering gall of the women at the heart of small but burgeoning cottage industry in Saharan Africa.

“It’s a book about books,” says Gordon. Specifically, it’s a book about the Nigerian women who write books. Novels in the genre of Littattafan Soyayya (roughly translated as “love literature”) are written by women, for women. They are escapist fantasies as much as they are cautionary tales; they are marriage and relationship advice told in the vernacular. Littattafan Soyayya might, on occasion, challenge the standing order in predominantly Islamic northern Nigeria, but it can as easily deny it.

“Some of the books are political but some are typical romance novels like you’d find anywhere in the world – stories of the poor girl who gets to marry the rich handsome man,” says Gordon.

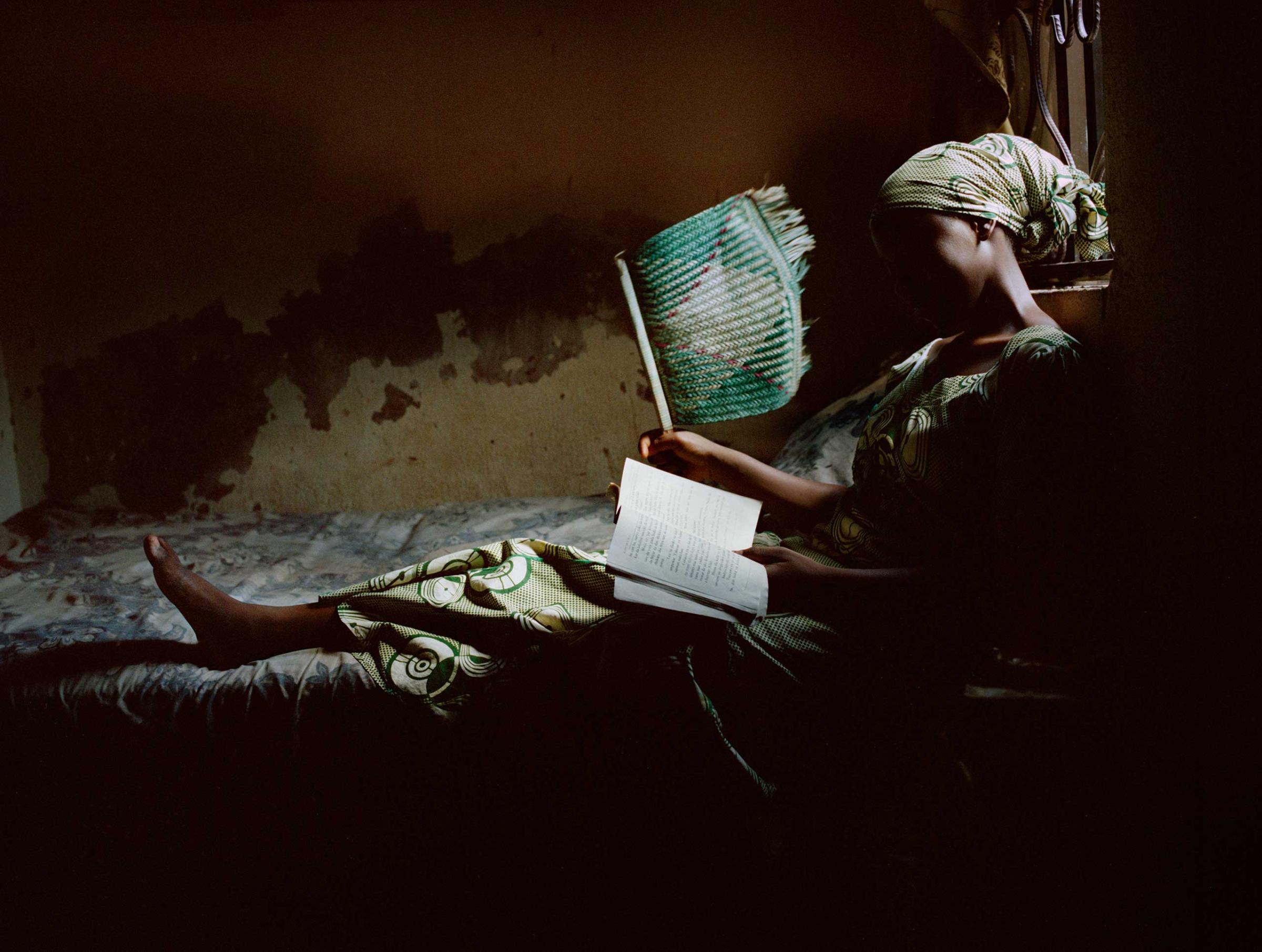

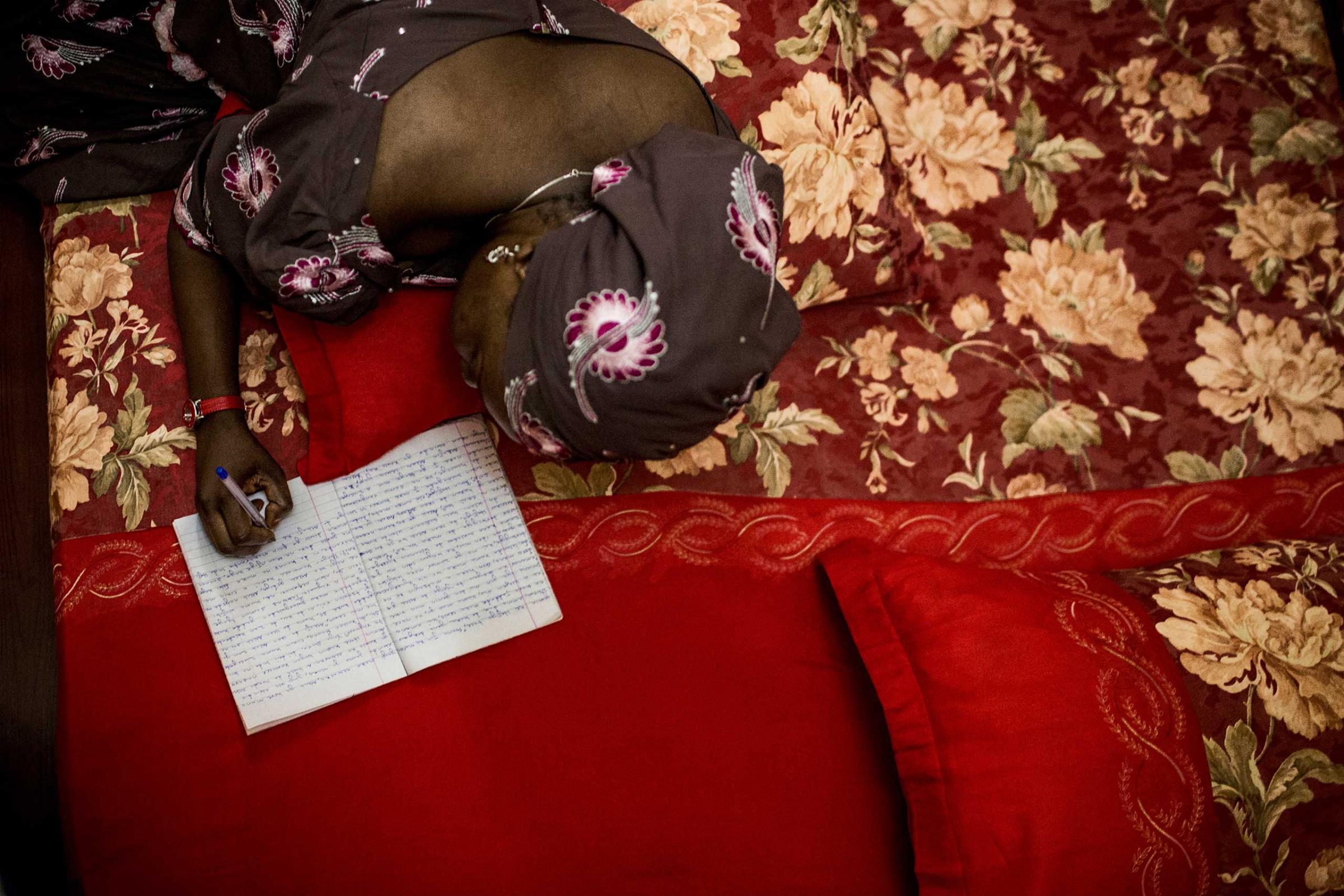

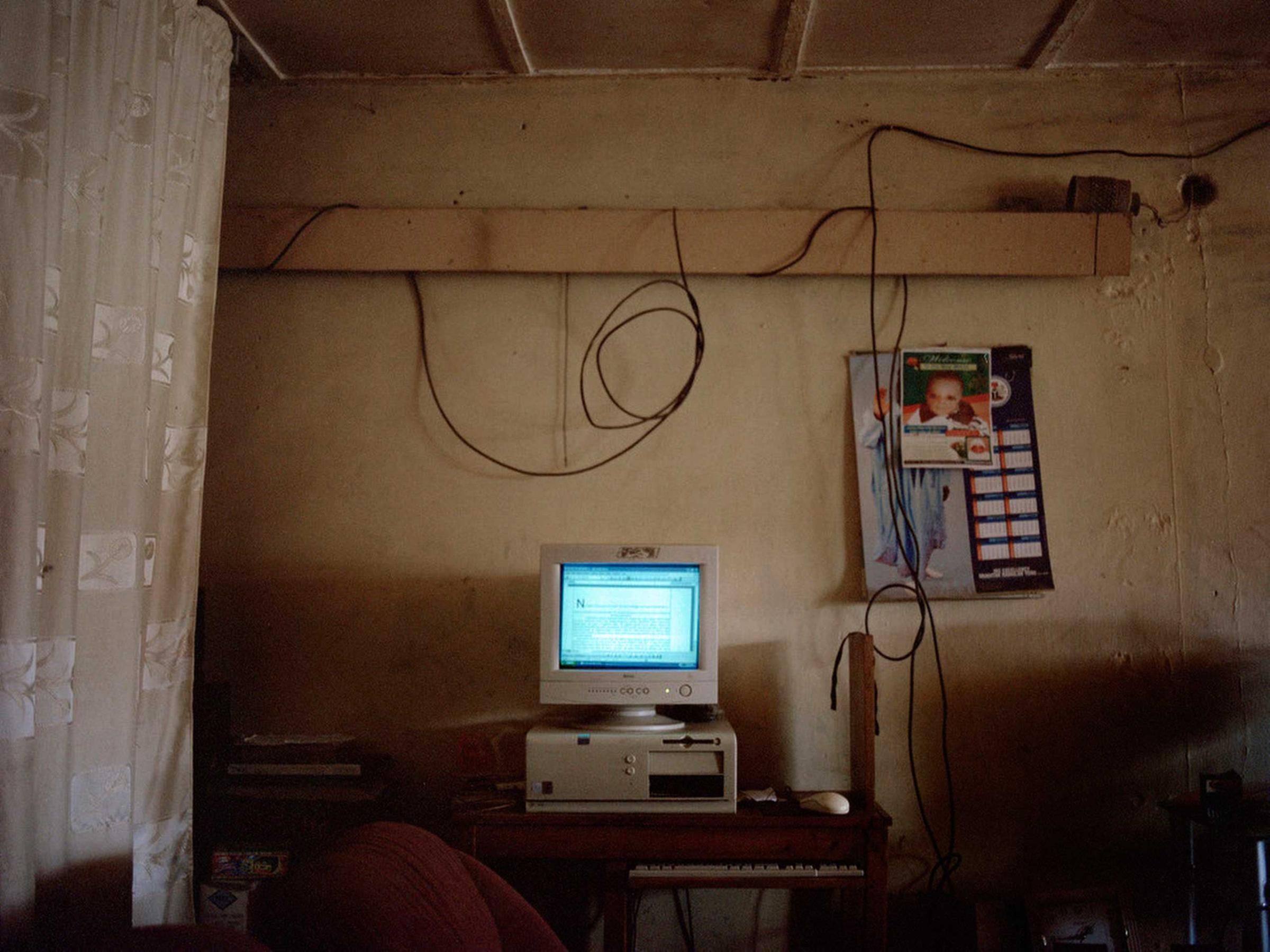

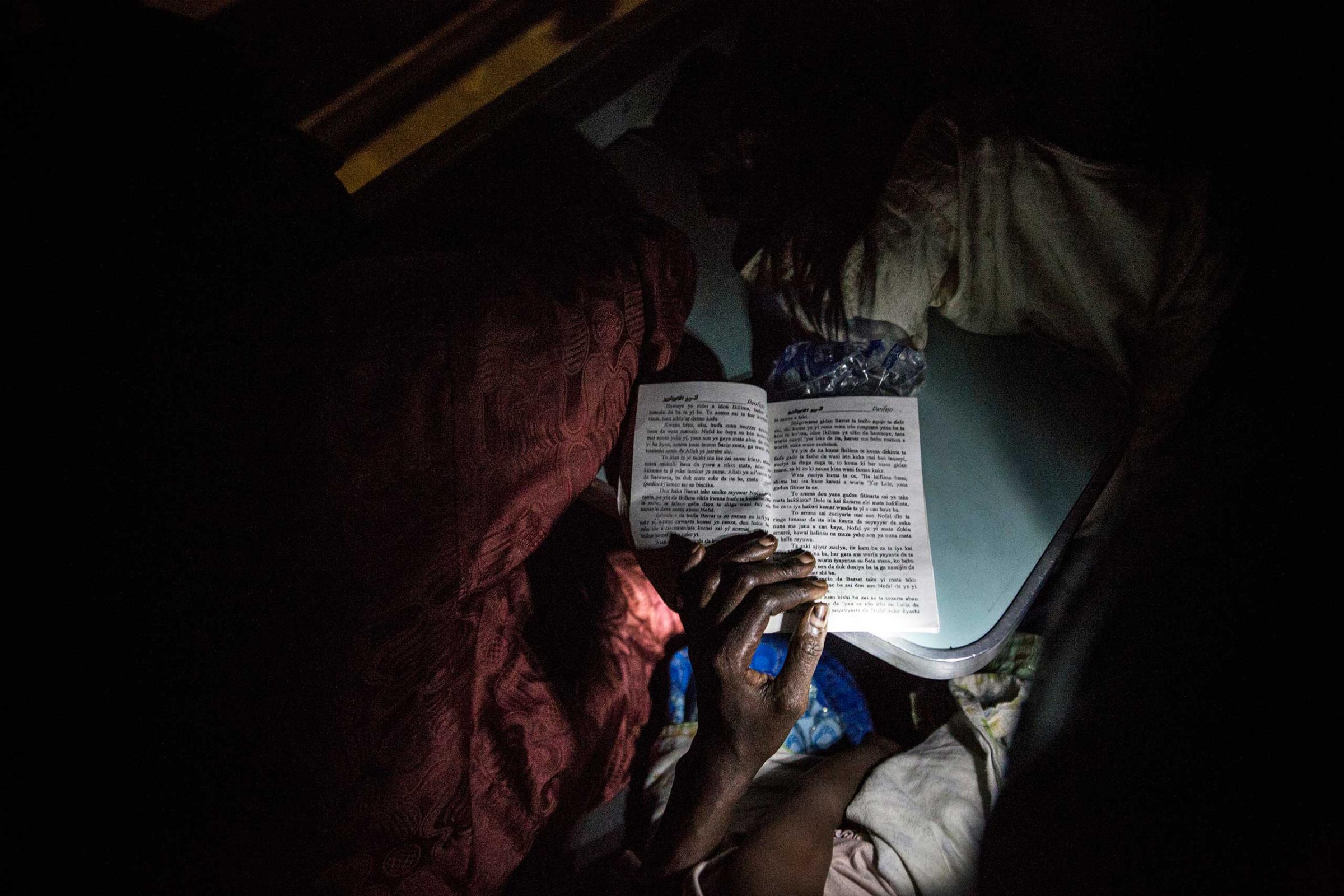

Diagram of the Heart introduces us to authors like Amina Hassan, who adores Jane Austen novels, and Jamila Umar, who was tired of male shop keepers not paying her properly for books so she opened her own shop. Gordon even met Balaraba Yakubu whose book The Wife of Father is a Test founded the genre. Diagram of the Heart depicts the work, the relationships and the social institutions from which Littattafan Soyayya has emerged. Women write in composition books in bedrooms. They sit in quiet contemplation. Gordon’s close-up shots of round red lips, henna-painted feet and other personal touches remind us at every turn that the view afforded within the pages is unlikely, privileged and without Gordon, otherwise impossible. This is the behind-the-scenes look, if you will, on romance schlock in the most unexpected of places. Schmaltzy tales might be the last thing American and Western audiences expect to emerge from the Sahel, but that’s precisely the point.

“Most of the stories coming out of Northern Nigeria these days are about Boko Haram,” says Gordon. “And almost all of the stories about women from Northern Nigeria are women who escaped being held captive by Boko Haram. Those are incredibly important stories, but they are stories that demand an explicit kind of emotional response – sympathy, outrage, pity. They are stories of injustice that require viewers respond by saying, ‘That’s not how the world should be!’ And they are right – that isn’t how the world should be. But, I also feel deeply aware of our limitations to instigate change, and I am wary of the role of photographs in that process.”

Gordon’s healthy skepticism toward the medium appealed to publishers Red Hook Editions.

“Too much coverage of sub-Saharan Africa is exotic, romantic, or worse,” says Alan Chin, one of Red Hook Editions’ co-founders. “While Glenna pays due deference to those elements in her photographs, her body of work brings us down to earth and into these women’s lives in a comfortable, ordinary way, without being boring. A tough and delicate balance, for sure.”

Visually, viewers are catapulted from the book’s signature dimmed, domestic interiors into public spaces such as markets, administrative offices and wedding halls that burst with color and activity. Invariably, men and women occupy separate physical spaces. Some pictures are astounding. In one, women sit on tiered seating, an arrangement that looks like the bleachers of a high school basketball game. But we learn it is in fact a mass wedding for widows, divorcees and other unmarried women, organized by Hisbah, a community-sanctioned Islamic “morality police” who censor novelists, arrest prostitutes and beggars and round up young men with mischievous haircuts.

In 2007, the then-state governor of Kano publicly burned hundreds of romance novels claiming they polluted the minds of young people.

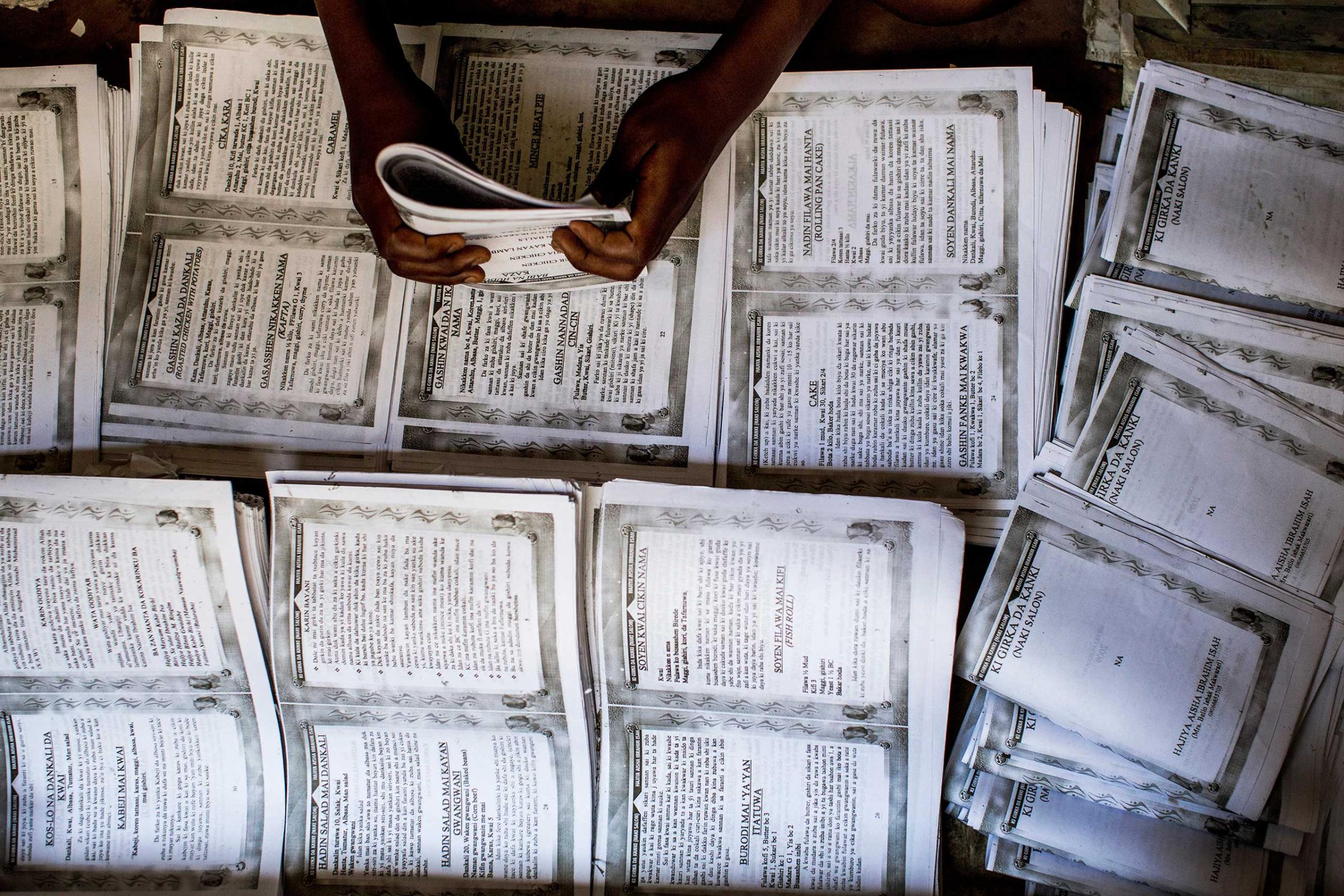

“After that, women were required to register with the Hisbah to get something similar to ISBN numbers,” says Gordon. “I never heard of any writers being arrested for racy scenes, but I do believe the books on the whole became less racy around that time.”

To help us familiarize ourselves, Gordon punctuates the narrative with photos of book covers, scenes from seller stalls and even includes a cheap fold-out henna design guide as an insert inside the back cover. They’re guides sold at every market in Nigeria.

“We toyed with the idea of facsimiles of these guides,” says Bonnie Briant, who designed Diagram of the Heart. “But then Glenna just said “Why don’t I have them made in Nigeria?” which was a fantastic idea – until she had to carry 1,600 of them home! But that effort really gets to what the project is all about.”

Also included are excerpts from novels—including What Is More Painful Than This, Women, You Can Capture Your Husband’s Heart! and Dreams Fulfilled—translated by Carmen McCain, some appearing in English for the first time. Most haven’t gone beyond Northern Nigeria before. This is a point of pride for Gordon.

“The women take their work very seriously but receive no outside recognition,” she says. “To them, I represented a kind of external validation. Many of them are incredibly successful on their own but because of the difficulties of translations, Hausa literature is often ghettoized and doesn’t receive the same kind of attention that Nigerian literature in English.”

Not everything in the design process was smooth sailing.

“We circumnavigate the traditional publishing route giving the photographer almost complete control,” says Jason Eskenazi, cofounder of Red Hook Editions, “Each book has its own individual character and design that more often than not is an extension of the photographer.”

Eskenazi, Chin and fellow cofounder Peter van Agtmael, were all active in sequencing discussions. Gordon and Briant ping-ponged edits regularly and drilled down on the strongest version quickly. The Red Hook way can be liberating. “Since they are all photographers they know when to allow a project to grow organically and when to step in,” says Briant. “They are one of the few publishers who has never said ‘No’ to any idea, just ‘Let’s see if it works’.”

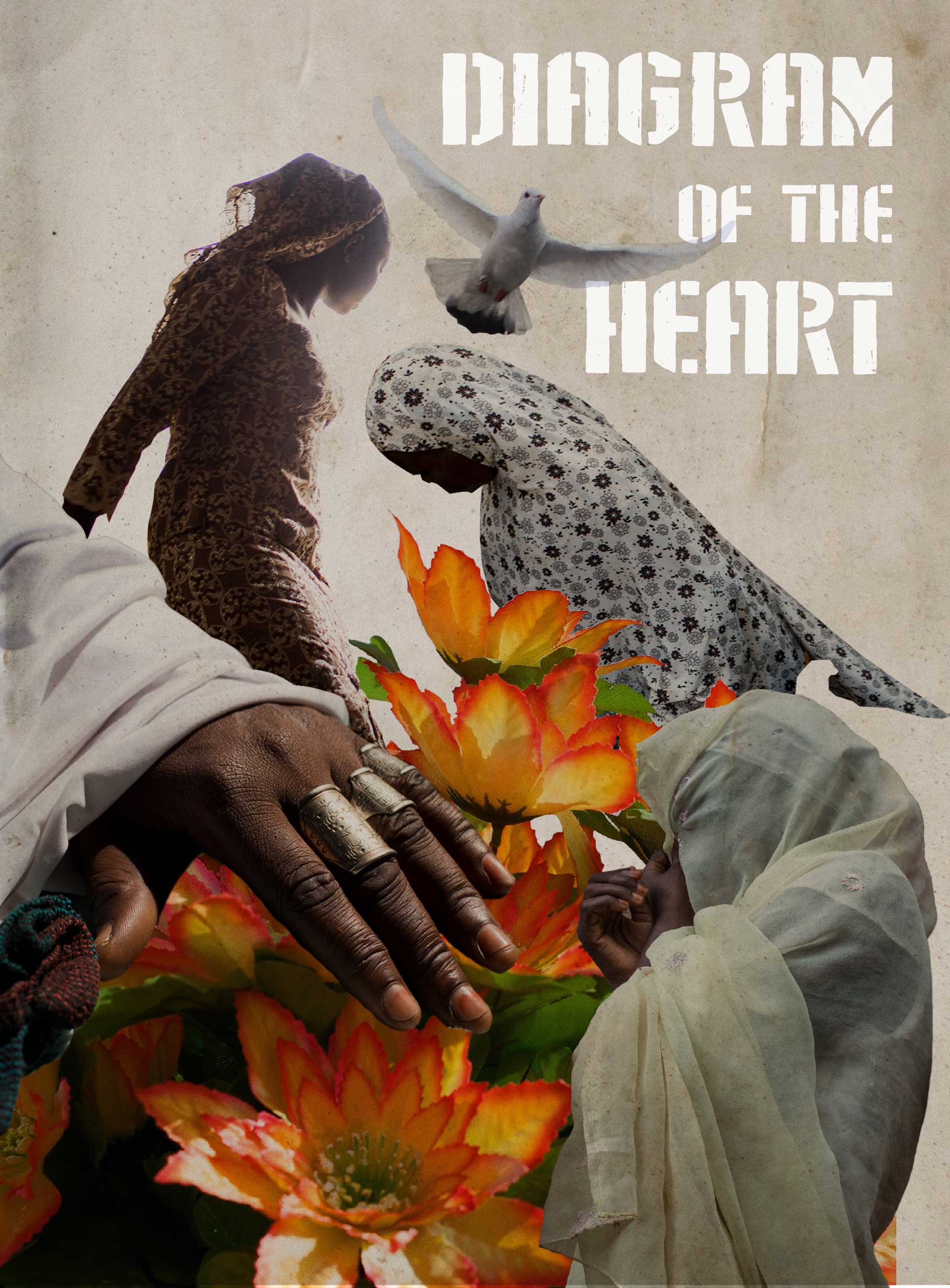

However, decision-making by committee can make for heated discussion. While finalizing the edit was relatively straightforward, the cover was less so. Very late in the day, Eskenazi vetoed the planned cover. “Don’t judge a book by its cover, but make sure you have a good one!” says Chin of Eskenazi’s high standards. Eskenazi wanted a cover that referenced the collage and zany covers of Littattafan Soyayya novels. Briant stepped up.

“We had all the pieces in front of us! Glenna’s pictures had all of those textural elements hidden in them,” says Briant whose own collage for the cover fuses six different images and breaks with reality. “I think we stepped out on a limb and the limb held.”

Relief all round. “At the time it felt overwhelming to change the cover, but Jason was totally right and I’m happy he pushed us to do that,” says Gordon.

Despite reluctance to qualify the exact changes her, or any one else’s, photography can bring, Gordon does hope Diagram of the Heart can pierce preconceived notions.

“What if a photo of a woman writing a book was as important as a photo of a man fighting a war?” she asks. “What would our foreign policy objectives be? How would we understand and conceptualize places and people we haven’t personally encountered? It often seems to me that fear is one of the driving forces behind the way America interacts with the rest of the world, especially the Muslim world. What if we filled those blank spaces onto which we project stereotypes with visualizations of the specific textures, colors and nuances of a life that is lived on terms different than our own?”

Glenna Gordon is a photographer based in New York. Her book, Diagram of the Heart, is published by Red Hook Editions.

Pete Brook is an independent writer and curator whose work focuses incarceration, power and images. He is founder of Prison Photography and editor of Vantage.

Michelle Molloy, who edited this photo essay, is a senior international photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com