Prior to the momentous Arab Spring that thrust the country into the global spotlight in 2011, Spanish photographer Miguel Ángel Sánchez and journalist Nuria Tesón set up a secret studio, where they photographed 80 Egyptians who agreed to tell their stories about life in Cairo before, during and after the revolution. The result was a photo essay that captured a changing Egypt through everyday people. Five years later, they returned to find these men and women now living in a culture of fear.

“They were afraid,” Sánchez tells TIME. “Many people, even bloggers and activists who raised their voices in the revolution, they have fear for speaking out against the new regime. But they still had something stronger inside that made them talk. It was something they felt was more important than their fears.”

Following the 2011 ouster of longtime President Hosni Mubarak, Mohamed Morsi, leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist party that was banned before the revolution, was elected as the country’s fifth president. But in 2013, as tens of thousands Egyptians gathered in Tahrir Square, accusing Morsi of betraying the goals of the Jan. 25 revolution, the army, led by the then defense minister Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, seized power, leading to a clampdown on Muslim Brotherhood members and supporters, as well as civil liberties across the country. In recent weeks, the situation has only worsened.

Sánchez and Tesón left Madrid for Cairo in 2009. They created the MÁSTESÓN collective, working together as a team – Sánchez photographing and Tesón writing, though each is involved in the other’s duties. Finding themselves at the center of one of the country’s greatest political and social storms, they brought a distinct visual and verbal perspective to 21st-century Egyptian society.

Cairo has become an oppressive, suffocating environment, Tesón says. “Every person who walked into our studio for an interview or to pose in front of the camera, was opening a kind of window to take a breath, to get some air. Some leaned out to look while others lifted it slightly before letting it fall again. That’s the kind of fear the regime has instilled in them.”

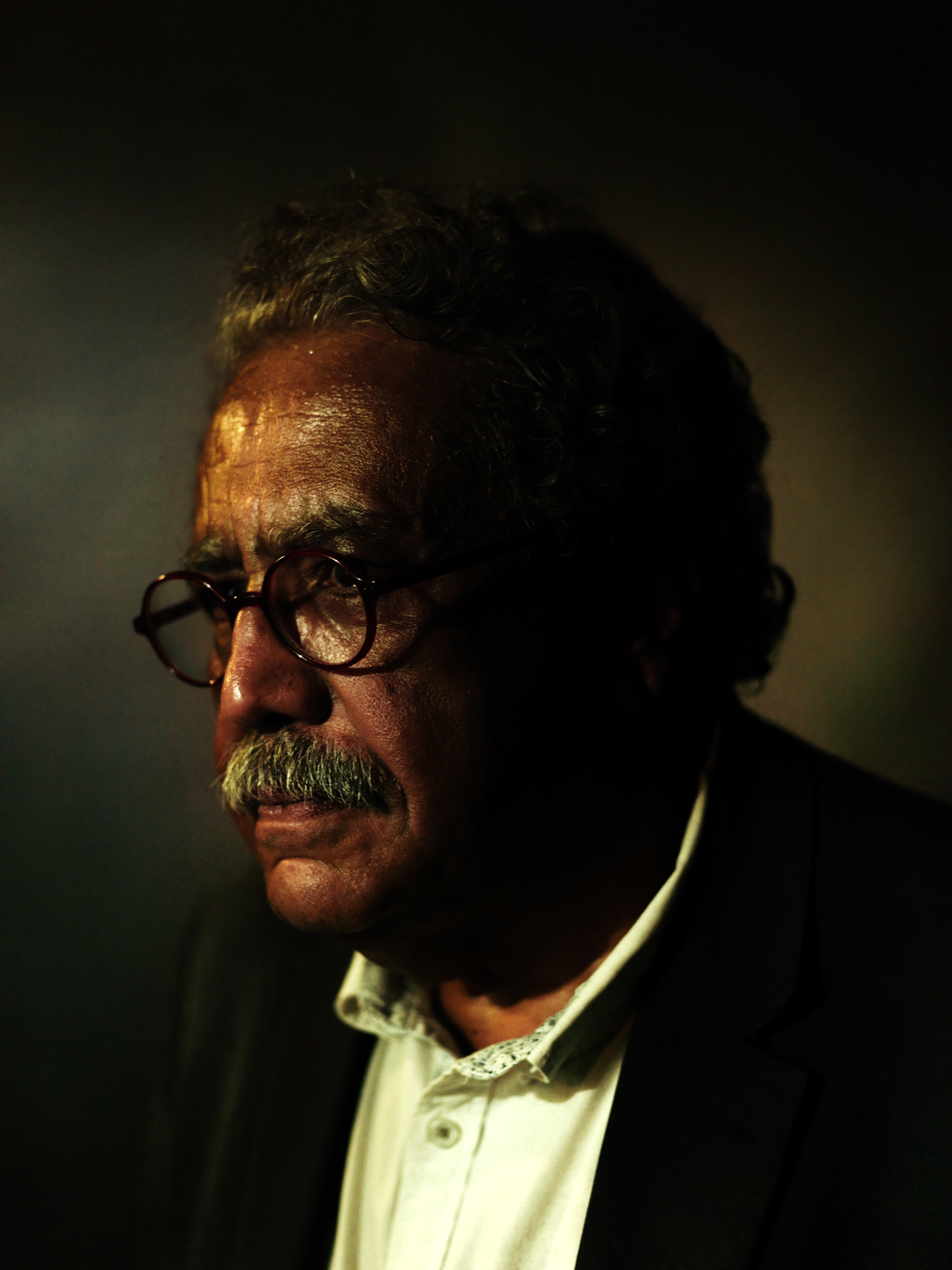

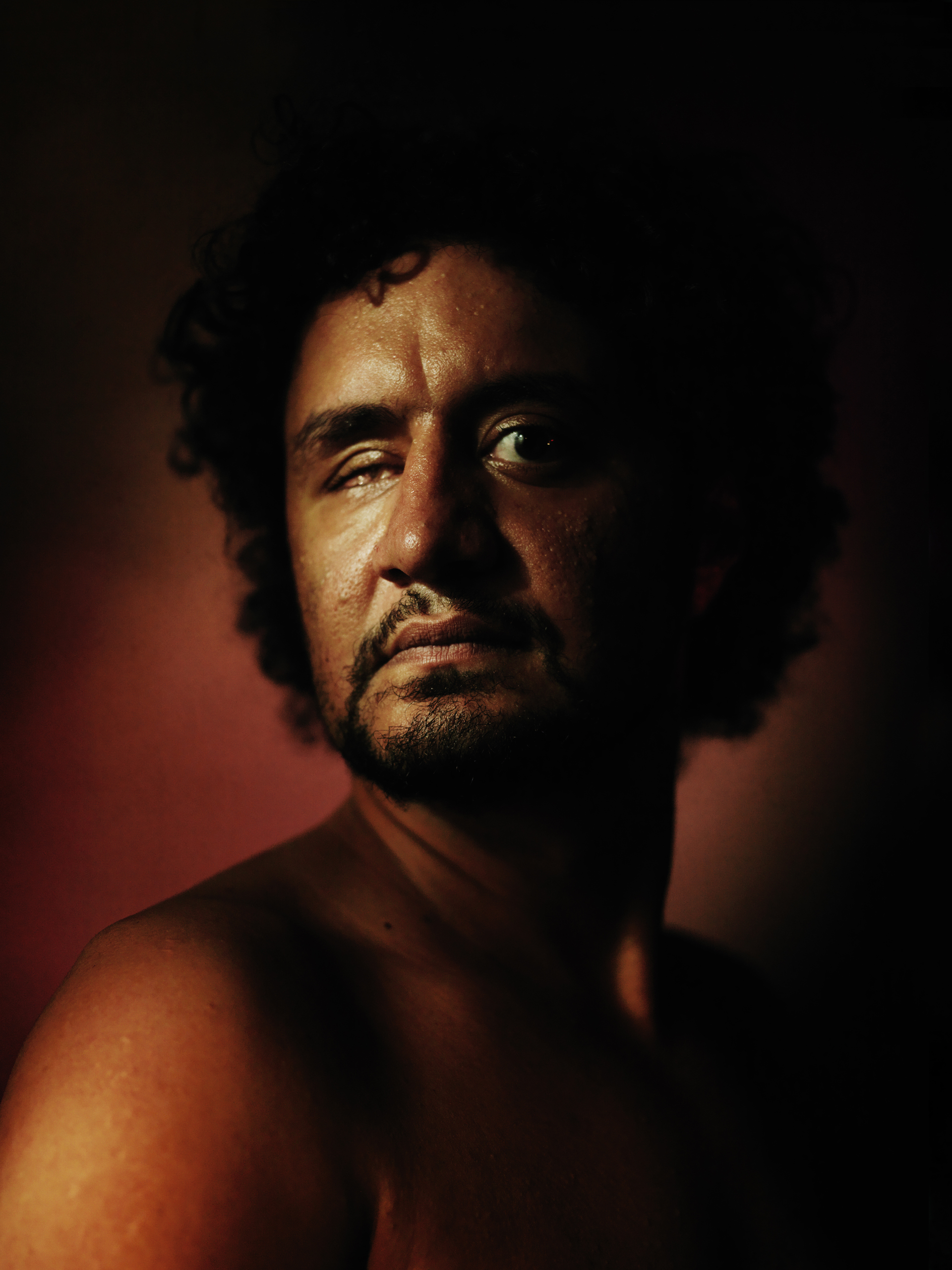

Sánchez did with the camera what the Baroque masters did with paint. Each image casts subjects in a dramatic contrast between light and dark, bringing together the realism of master painter Caravaggio. Their recent series introduces the 1950s hollywood portrait style, matched with the elusiveness of film noir: a style they say best reflects the atmosphere they felt in Egypt.

“We found inspiration in the city,” Sánchez says. “When you are part of this bubble of noise, smells and lights, you feel that Cairo is holding a momentary silence, a painful and depressing rest. It’s as if the city is holding its breath, which is about to explode with voices demanding freedom, justice and a better life. We wanted to portray this tension in our written and photographic portraits.”

His images go beyond the common shot of protest crowds, to capture the individual: bloggers, lawyers, politicians, artists, activists, even mothers of martyrs. They are the denizens of a modern capital city, everyday people who are protagonists in the intimacy of his studio.

One man rests his head in their hands in fatigue while another, a journalist who lost his eye while covering the protests of the Egyptian uprising, sits back, shirtless and half smoking a cigarette. A woman, a psychiatrist who said she was sexually assaulted by the security officers because of her activism, looks, full of hope, somewhere beyond the frame. Another man removes his sunglasses and shows a glass eye with the word ‘freedom’ in Arabic written on it.

“There is a kind of spirit that erupted with the revolution and cannot be erased,” says Tesón. “They are not scared anymore and they are not going to be shut down again. They have a voice, they have an opinion, they believe in the ideas of the revolution and they are working against everything to keep the flame of this idea going forward.”

Shooting with a medium format camera, Sánchez uses bold lighting and shadow to create the composition he wants. Before photographing his subjects, he simply asks them to look into the camera. While the technicalities help achieve the stylistic effect, in the end, Sánchez says it’s not about the sketches or the drafts or the lighting. “This work is about the people, the city, the sounds, the dreams, the life and the death.”

Miguel Ángel Sánchez is a Spanish photographer and Nuria Tesón is a Spanish independent multi-media journalist and writer. Both are based in Turkey after living in Egypt between 2009 and 2014. Check out their work here.

Michelle Molloy, who edited this photo essay, is a senior international photo editor at TIME.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @rachelllowry.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com