Excerpted from TIME’s David Bowie: His Life on Earth, an 80-page, fully illustrated commemorative edition. Available at retailers and at Amazon.com.

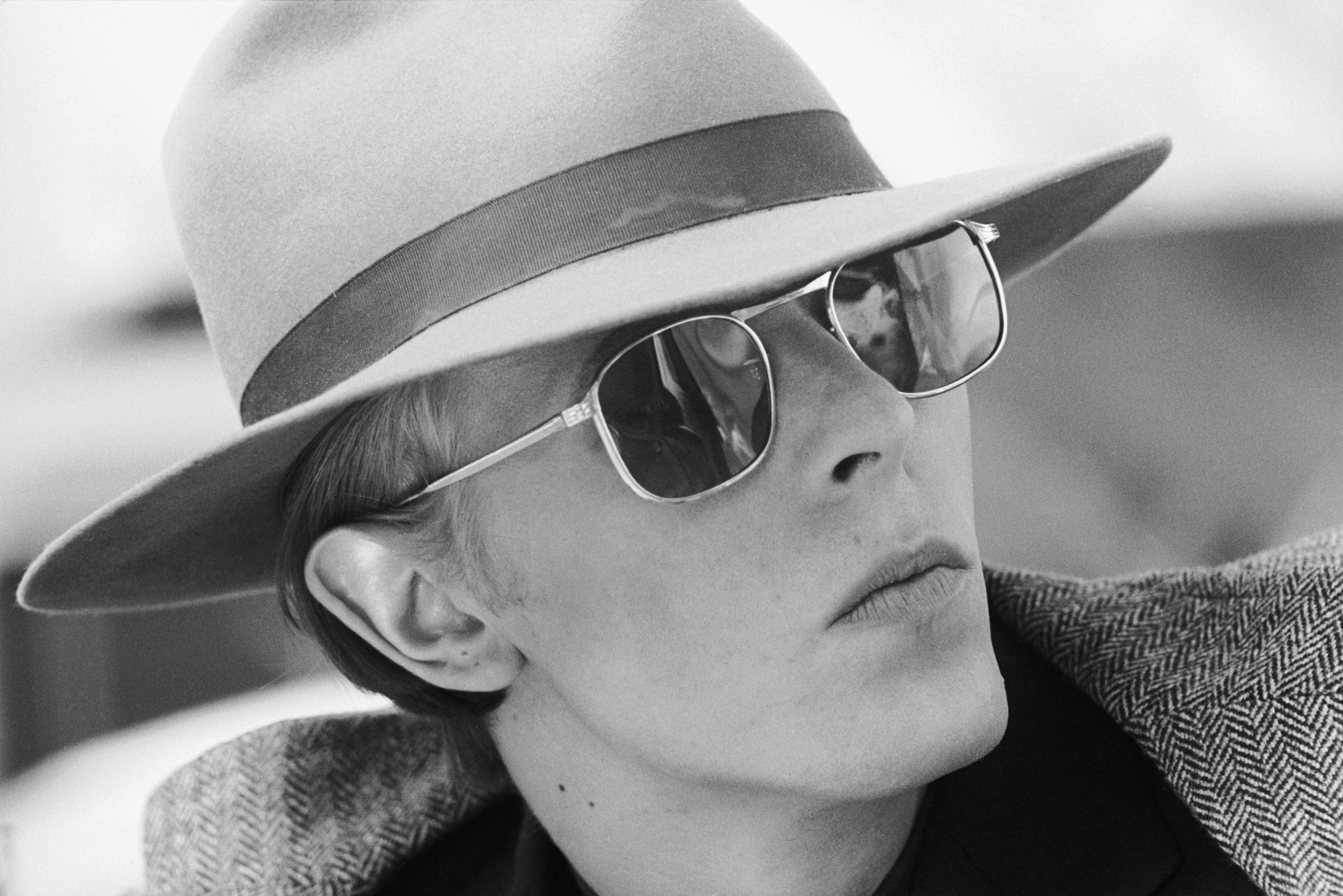

Call him clairvoyant: Way back in the 1970s, David Bowie envisioned key parts of our culture today. During the most crucial decade in Bowie’s career, his forward-thinking approach to sexual identity, celebrity image and musical presentation tipped off many of the hot-button issues that currently obsess us. Think about it: the way social media allows us to create alternate selves at will, the manner in which society increasingly views gender as fluid, as well as the theatrical identities of modern stars from Daft Punk to the hip-hop collective Odd Future all have seeds in Bowie’s quick-change run of characters in the ’70s. Ziggy Stardust, the Thin White Duke and the Man Who Fell to Earth, taken together, made a statement that rejected the very notion of a fixed self. At the same time, they gave rock a wholly new theatrical flourish.

Read more: See TIME’s David Bowie cover.

Just as prime-time Bowie tried on and discarded characters as blithely as one would clothes, so he ran mad through a dizzying range of musical styles. He made innovations in art pop, glam rock, German industrial music and more, along the way minting a dense discography of classics. During that pivotal decade, he didn’t release a single less than defining work, creating a dozen successive touchstones.

While Bowie’s lithe figure and pretty face gave him an androgynous aura from the start, he didn’t use that role in so focused, and shocking, a way until the U.K. cover of his 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World. It found him draped over a chaise longue wearing a dress and sporting long tresses that seemed less like the hippie casual norm of the day than like something out of old Hollywood. When he appeared in a similar fashion for an interview with Rolling Stone, its writer described him as “ravishing” and “almost disconcertingly reminiscent of Lauren Bacall.” Even so, Bowie’s U.S. label of the era, RCA, reissued the album in a less provocative cover, depicting Bowie in a more common rockstar pose: a macho kick. The music inside led Bowie in a harder-rocking direction than its folk and pop-leaning predecessors. The title track proved enduring enough to inspire an aching cover version by Nirvana on their 1994 concert album, MTV Unplugged in New York.

It was Bowie’s next work, Hunky Dory, that kicked off his classic run. On one level, that 1971 album seemed to boldface the star’s influences, with one track titled “Song for Bob Dylan” and another “Andy Warhol.” A third cut, “Queen Bitch,” nodded to the decadent rock flash of the Velvet Underground. At the same time, Bowie transformed those references into a sound very much his own, marked by high-drama vocals and a deep melodic command. “Life on Mars?” had such a theatrical flair, it later provided a suitable cover for Barbra Streisand. Bowie advertised his ability to move swiftly between all these styles with the album’s opening proclamation, “Changes,” a song that doubled as a mantra.

To that end, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars found him performing in an entirely new guise, as the title character backed by his raging Spiders rock band. “Offstage, I’m a robot; onstage, I achieve emotion,” Bowie said back then of his love of assuming characters. “It’s probably why I prefer dressing up as Ziggy to being David.”

Bowie’s decision to do so, along with his costumed and highly stylized live show, offered a total rebuke to the naturalist approach of the previous hippie era. He presented artifice as the new authenticity, while also holding to rock’s ballsy power in tracks like “Suffragette City.” His mix of the arch and the primal blueprinted a new scene in music: glam rock. It wasn’t just the sound that had a fresh edge. In a 1972 interview with Melody Maker, Bowie declared himself to be gay, an extremely daring move at the time. During his live show, Bowie sometimes simulated giving oral sex to his guitarist, Mick Ronson. In a 1976 interview with Playboy, Bowie hedged, labeling himself “bisexual,” though in a talk with Rolling Stone in ’83, he switched things up again, saying he’d always been a “closeted heterosexual.” Twenty years later, he lamented having to discuss it at all, telling a U.K. talk show that most journalists still wanted to rehash the same issues. “David Bowie: bisexual. Drugs. Likes cats. Whatever it is they have on their checklist.”

The ultimate truth of Bowie’s personal life (cats? dogs?) mattered less than his insistence on publicly blurring the definitions of sexual identity, or even giving them an otherworldly allure. The music, however, could not have been more potent, from the glam-rock slap of “Watch That Man” to the hip-shaking ode to one of his rock heroes, Iggy Pop, “The Jean Genie.”

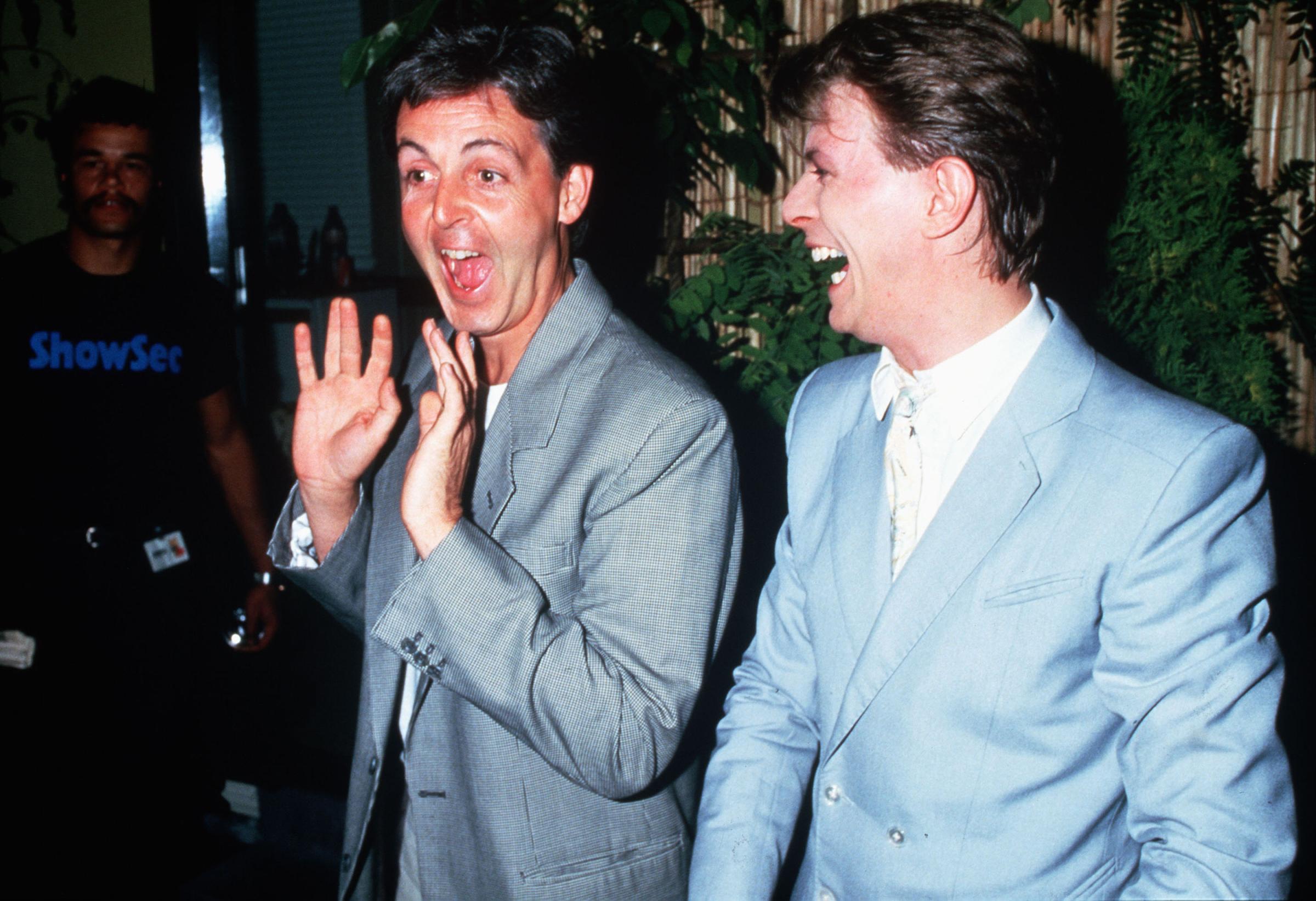

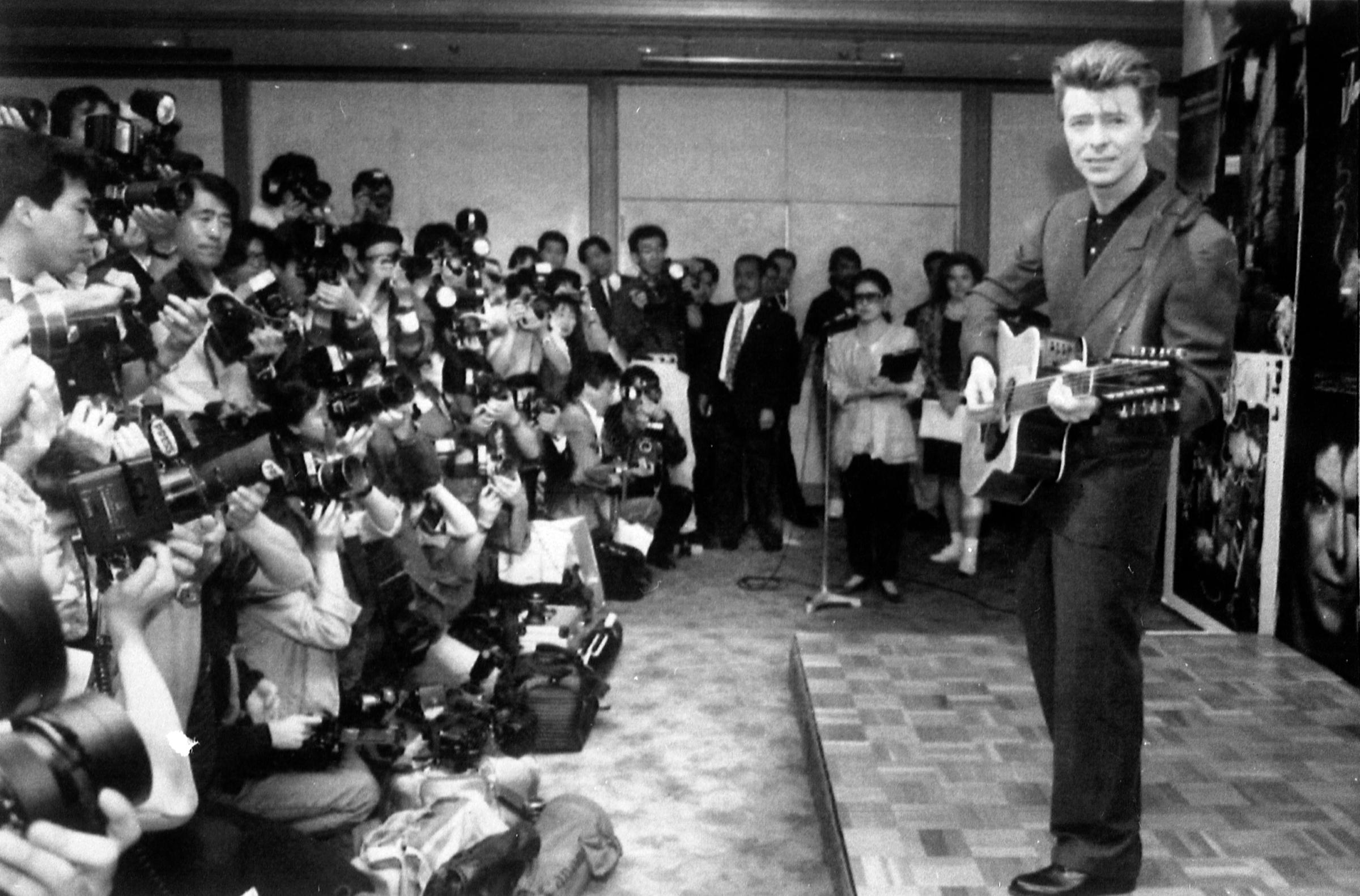

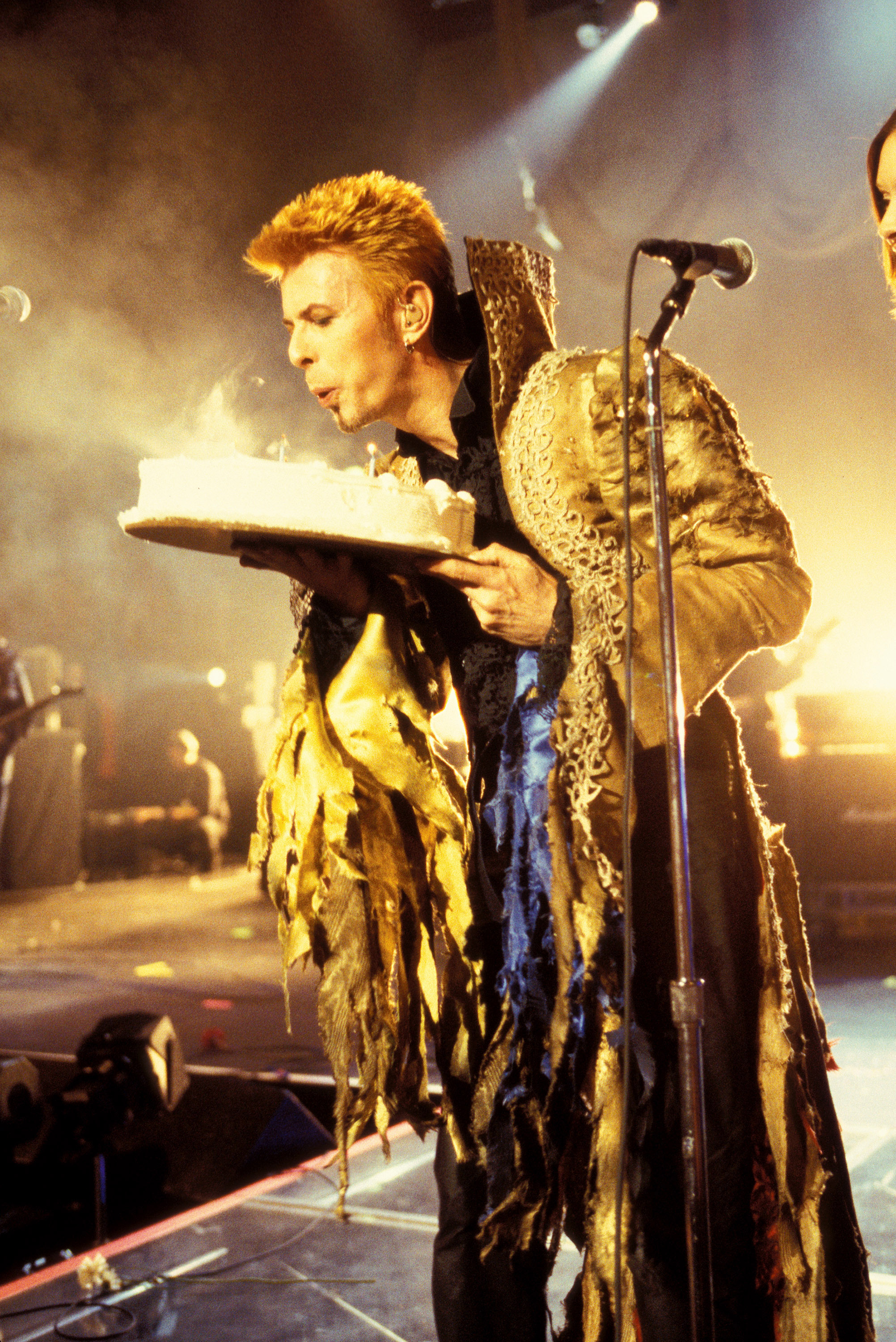

The Many Faces of David Bowie

Bowie could have tarried longer on the glam-rock bandwagon he had helped create, but he changed yet again on 1975’s Young Americans. Enlisting a talented but then little known singer, Luther Vandross, who co-wrote a track and helped with arrangements, Bowie offered what he called “plastic soul,” a cheeky label for his co-opting of African-American R&B and funk, heard in hits like the title track and the No. 1 dance standard “Fame.”

Bowie’s description of the music may have advertised its inauthenticity, but that only enhanced his consistent outsider stance. In 1976 he varied his new dance-funk sound on Station to Station, adding elements of avant-garde German rock, an interest he would elaborate exponentially on in his next three releases, together known as the “Berlin trilogy.” Collaborating with Brian Eno on the albums Low, Heroes and Lodger, Bowie nudged the avant-garde a little closer to the mainstream. The albums also produced pop mainstays, from the track “Heroes” to the bisexual ode “Boys Keep Swinging.” After the equally creative Scary Monsters in 1980, Bowie would head off into a far slicker direction while, in future decades, he swung back to darker and more challenging sounds, keeping him new to the end. Yet for all the vividness and daring of his subsequent recordings, the ’70s remains Bowie’s most visionary era, the time when he established himself as the Nostradamus of modern pop.

Excerpted from TIME’s David Bowie: His Life on Earth, an 80-page, fully illustrated commemorative edition. Available at retailers and at Amazon.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com