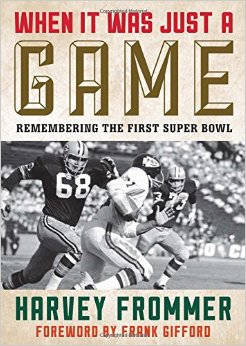

The first American Football League-National Football League Championship Game was played on Jan. 15, 1967. It was the only “Super Bowl” game to be telecast by two television networks, to use two different footballs, to have two kickoffs for the second half, and to fail to sell out. Tickets at $15, $12 and $10 were thought to be overpriced.

For a while, no one knew exactly what the new game was all about—especially with two Midwestern teams, the Kansas City Chiefs and Green Bay Packers, in it. Prior to that first game, those two teams had never played against each other, and no NFL team had ever played against an AFL team. When the two leagues merged in June 1966, one of the provisions of the merger was the creation of a championship game. Now the only problem was what to call it.

In 1960, at an NFL owner’s meeting, deliberations had dragged on and on to select a new National Football League Commissioner to replace Bert Bell, who had passed away. Young Pete Rozelle hung out in a Miami hotel men’s room for a couple of hours and adjusted his tie, looked away, or washed his hands whenever anyone entered. He later guessed that he had washed his hands 35 times while waiting around. Then he got the news—at 33 he was the new NFL Commissioner.

Flash forward to 1966 and the upcoming championship game. One of Rozelle’s suggestions for the name of the new game was “The Big One.” That name never caught on. “Pro Bowl,” was another Rozelle idea. Had the name been adopted, there would have been confusion, for that was the name used for the NFL’s All Star game. “World Series of Football” died quickly, deemed too imitative of baseball’s Fall Classic.

Finally, it was Rozelle’s idea to call the game “The AFL-NFL World Championship Game.” That name was official, but it never took off. It was too cumbersome, a mouthful, no good for newspaper headlines. It was Lamar Hunt, the main founder of the American Football League and owner of the Kansas City Chiefs, who came up on the term “Super Bowl.” As his son, Lamar Hunt Jr., explained, the idea came from his “Super Ball” toy.

My dad was in an owner’s meeting. They were trying to figure out what to call the last game, the championship game. I don’t know if he had the ball with him as some reports suggest. My dad said, “Well, we need to come up with a name, something like the ‘Super Bowl.'” And then he said, “Actually, that’s not a very good name. We can come up with something better.” But “Super Bowl” stuck in the media and word of mouth.

On Jan. 15, two very different kinds of coaches and men faced off on the playing field.

Vince Lombardi out of Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, once an altar boy at his local parish, had never held a head coaching position beyond the high school level when he showed up on Feb. 2, 1959 as a tough-talking and determined 45-year-old for a meeting with the Green Bay Packer Executive Committee. They were interviewing him for the head coaching job. He wound up hired as head coach and general manager.

Lombardi was fond of exhorting his players to do nutcracker drills. Blood flowed freely. The Packers worked out with cracked ribs, broken bones and torn cartilage. Dehydrated players were sometimes sent off to the hospital. The Packer locker room at Lambeau Field featured a large sign that read:

What You See Here

What You Say Here

What You Hear Here

Let It Stay Here

Hank Stram of the Chiefs had all kinds of rituals and beliefs. He paid a great deal of attention to detail like having Dial yellow soap in the showers, thinking it reduced infections, like practicing over and over again the right way for a punter to give up a safety in his own end zone, like how his team ran out on the field to warm up, like replacing every shoe lace in every shoe prior to every game.

Both Stram and Lombardi were very religious and had one or more priests traveling with them and on the sidelines during games. Both coaches quoted scriptures.

The Chiefs under Stram and the Packers under Lombardi had no quotas of any kind, and they did much for diversity in pro football. It was estimated that there were more African-American athletes on the field that first Super Bowl day than at any other time in the previous history of a sport in which no franchise had selected an African-American player in the draft until 1949, 10 years after the start of the draft.

The Packers defeated the Chiefs, 35-10. All Commissioner Pete Rozelle had wished for was that the first AFL-NFL Championship game would one day surpass baseball’s World Series. It would do much more than that. That mythic game has become the grandest, grossest, gaudiest annual one-day spectacle in the annals of American sports and culture.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com