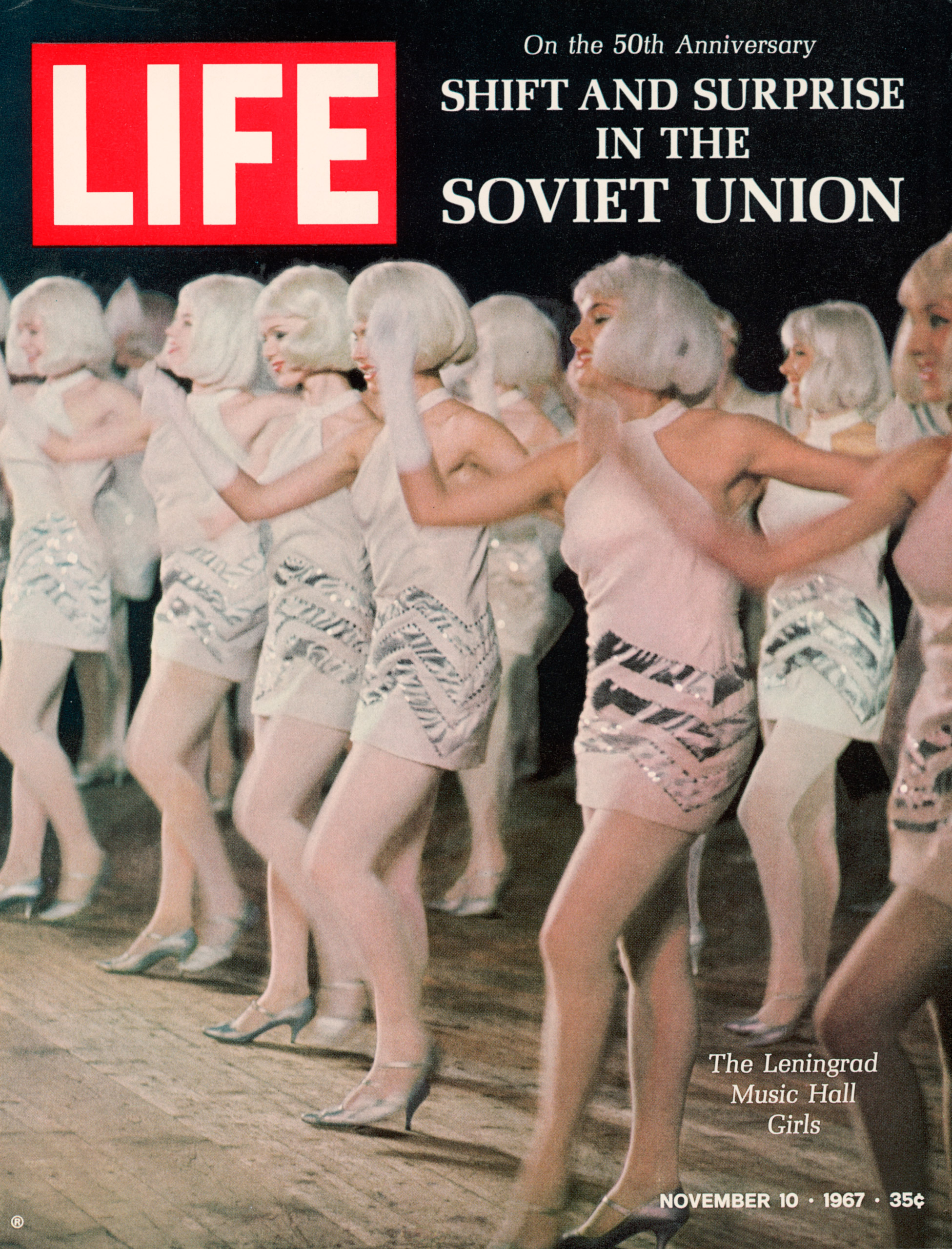

Readers who picked up the Nov. 10, 1967 issue of LIFE magazine, which commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, might have expected to see black-and-white images of bleak celebration: photographs of Moscow’s Red Square replete with drably dressed industrial workers and sloganeering bureaucrats. Instead, they were inundated with Technicolor images of Soviet youth in various states of undress: sunbathing at the beach, dancing at a nightclub and making out at the Festival of Neptune along the Black Sea.

Some might have considered these images, made by LIFE photographer Bill Eppridge, an unrepresentative sample of life behind the Iron Curtain. But he was onto something: by 1967, nearly half of the 235 million people living in the Soviet Union were under the age of 27, most of them born in the years immediately following World War II. Along with a decline in birth rates, the human toll of nearly four decades of violence—civil war, famines and the Second World War—created a demographic crisis that only a return to normalcy could resolve. By the time Eppridge arrived, the pendulum had swung decisively into the younger generation’s court.

This so-called “Sputnik generation” that frolicked in front of his lens grew up during the optimistic 1950s and entered adulthood in the early 1960s, at the beginning of the USSR’s “stagnation decade.” Unlike their parents, who might have cited late night knocks on the door and the Great Patriotic War as the defining events of their own young lives, the country they knew was the one that sent Yuri Gagarin and Sputnik into space and stocked shelves with Western-style consumer goods. When they pledged allegiance to the Soviet state in school, they faced a portrait of Vladimir Lenin or Nikita Khrushchev, not Joseph Stalin.

In the Soviet Union, as in many welfare states, the political was personal. State policies put in place during the 1950s, when the Sputnik generation was entering grade school, directly affected their private lives. One of the most consequential policies that Stalin’s successor Khrushchev implemented during his tenure as General Secretary was housing reform. He launched an enormous project to replace communal apartments with prefabricated, multi-story complexes. No longer living in tight, shared quarters, many citizens began to enjoy alone time and even separate bedrooms.

As members of the Sputnik generation enjoyed more autonomy at home, they sought out meaningful relationships with their peers outside of it. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, classrooms and public parks became the venues where Soviet girls and boys had their first tastes of unrefined vodka and suffered through first kisses. By the time they enrolled in college—which nearly 25% of Soviet high school students did thanks to increased state investment—they had their own personal networks to turn to when they wanted to get their hands on the latest banned Beatles album or share a ride to a summer festival.

On the surface, the freedom and mobility that Soviet youth enjoyed during the decades after World War II seemed to reflect that of middle-class American “baby boomers,” who were enrolling in college en masse, listening to Elvis and often rebelling against their parents. But where American youth committed themselves to social and political movements, Soviet 20-somethings channeled their energy into intimate relationships and intellectual development. When asked about her political engagement, a literature student in Moscow told LIFE correspondent Paul Young, “I just don’t care.” Though it may not have sounded like a traditional protest, this response in some ways represented a more total rejection of the establishment than those seen on the streets of New York or Mexico City.

But any sighs of relief the Soviet leadership might have breathed when they compared radical protests abroad to the seemingly content youth at home were premature. The challenges authorities faced during the 1980s laid bare the extent of citizens’ discontent in the face of a system that was quickly falling apart. The irony of the Soviet Union’s golden years is that they planted the seeds for the empire’s ultimate dissolution. Implementing policies that helped people live more comfortably, become more educated and enjoy greater personal autonomy temporarily rendered their political disenfranchisement slightly less egregious, but it could not produce loyalty.

When it came time to vote for the Soviet Communist Party’s disbandment in 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev discovered that he was the only committed communist left standing in a room filled with the apathetic and disillusioned. Everyone, it seemed, had turned on a different station, tuned in, and checked out.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com