Lost in the financial market turmoil in the first weeks of 2016 has been the abrupt change in Iran’s public posture on its post-sanctions oil export strategy. Several times in the past week, an authoritative Iranian petroleum industry official stated that Iran would shape its export strategy to avoid exacerbating pressure on crude prices. January 2, Bloomberg quoted Seyyid Mohsen Ghamsari, the head of international affairs at National Iranian Oil Company as saying that Iran:

“…will try to enter the market in a way to make sure the boosted production will not cause a further drop in prices. Production potential does not mean we will be entering the boosted production into the market or stockpile it. We will be producing as much as the market can absorb.”

January 6, according to Reuters, Ghamsari underscored Iran’s aversion to adding downward pressure to crude prices:

“We don’t want to start a sort of a price war. We will be more subtle in our approach and may gradually increase output. I have to say that there is no room to push prices down any further, given the level where they are.”

Ghamsari’s measured approach stands in sharp contrast Iran’s public posture in 2015’s second half, during which Iranian officials promised to push crude exports energetically as soon as the international community lifted sanctions. In September, soon after the P5+1 countries reached agreement with Iran on its nuclear program, Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh stated that “Production will rise immediately by a half-million barrels per day, and after four to five months, by an additional half-million barrels”. As the December 4 OPEC meeting in Vienna approached, Zanganeh asserted that Iran would not seek OPEC’s permission to export an additional 500,000 barrels daily and was not concerned about the impact on crude prices:

“The drop in prices won’t be a concern for us. It should be a concern for those who have replaced Iran.”

Why the Shift?

Several explanations for the shift in public posture are possible. One is that Iran’s immediate post-sanction aggressive public posture was a bluff—that Iran currently does not have the physical capacity to produce and export an additional one million barrels and cannot do so without substantial foreign investment. International sanctions on Iran over the years have eroded Iran’s oil production, transportation, and export infrastructure. The conditions of its oil wells likely deteriorated and require extensive maintenance, while many pipelines are in poor condition and potentially unfit to handle increased volumes.

Oilprice.com: Shocking: ISIS Attacks On Libyan Oil Facilities Visible from Space

Another (and not necessarily contradictory) explanation is that Iran recognizes its aggressive public posture is proving counterproductive—that it contributed substantially to the decline in crude prices in 2015. The following table provides the monthly OPEC basket crude price for 2015. In the first quarter, as global markets absorbed the shock from the shift in OPEC production policy at its November 27 meeting in Vienna, crude prices began to stabilize.

In the second quarter, prices increased as markets anticipated supply and demand soon would balance. In the third quarter, however, as an agreement between the P5+1 countries and Iran grew increasingly likely, markets anticipated that the end to limits on Iran’s oil exports would delay rebalancing and prices resumed their decline. In the fourth quarter, Iran’s assertion that it would increase exports by one million barrels per day in the course of 2016 exacerbated the downward pressure and the OPEC basket price reached its 2015 nadir at $33.6. In January, the OPEC basket price reached ~$30 per barrel.

The decrease in crude prices means that the incremental 500,000 barrels per day will now generate less net export revenue for Iran than exporting only one million barrels at $45 per barrel. Assuming that increasing the total incremental export volume to one million barrels per day would cause the OPEC basket price to drop an additional $5, to $25 per barrel, net revenues would fall further (annual revenues net of the $15 production cost).

Of course, Iran will generate more net revenue exporting 1.5-2.0 million barrels daily than it will exporting only one million barrels at $30 per barrel. However, Iran desperately needs foreign investment in its oil industry. Due to low crude prices, Iran’s investment in its oil industry has dropped to a trickle.

Oilprice.com: Rig Count: Capitulation?

Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh put investment at $6 billion in 2014, and given the continued decline in prices in 2015, investment likely at best remained at this level. Saeed Ghavampour, strategic planning general manager in Iran’s oil ministry put the investment requirement at $100-$500 billion over the next five years. Goldman Sachs put the requirement at $30 billion over five years, and envisaged 350,000 barrel per day incremental output.

At such low crude prices—and given the uncertainty about the timing and extent of any recovery–however, investing in the Iranian crude industry loses its financial luster. According to the investment contract the Iranian government is promoting, the foreign investor will be the junior partner in a three-party investment group that includes the (cash-strapped) Iranian government and the obligatory (and likely cash hungry) Iranian partner.

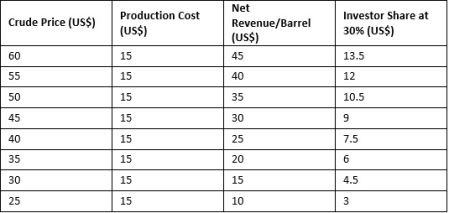

What share of revenues can this junior partner—whom the Iranian government undoubtedly expects to provide the capital, equipment, and expertise–expect? One third? One quarter? Fifteen percent? The following table shows the revenue per barrel a foreign investor could expect at various OPEC barrel crude price points, net of the $15 production cost, assuming a 30 percent share:

High Risk, Modest (at best) Rewards?

Rather than decreasing, as anticipated in the run up to the P5+1 agreement, the risks involved in investing in Iran have increased. The intensifying conflict with Saudi Arabia and its Gulf Arab allies is one risk. Victor Shum, IHS Singapore oil market chief, described the conflict as adding “to the calculus of making a long-term capital investment decision in Iran. It will slow down investment, possibly by months or even years, and slow the addition of new output”.

Oilprice.com: Is $20 Oil A Possibility?

Within Iran, the opening to the West (and restrictions on the nuclear program) faces determined resistance from influential power centers—the Revolutionary Guards, the military, the nuclear establishment, and conservative clerics among others. They have expressed their opposition both to attracting Western investment to the energy industry (complicating the oil ministry’s efforts to design, confirm, and present an attractive foreign investment contract) and to the West in general (conducting UN-resolution banned ballistic missile tests, arresting, trying, and imprisoning U.S. citizens, expanding military operations in Syria, and supporting Houthi rebels in Yemen).

Finally, investors are unlikely to make significant commitments (or any commitments whatsoever) until they are certain about U.S. policy—and U.S. policy won’t be settled until the 2016 Presidential and Congressional elections are over. A Republican president and Congress could (in fact are likely to) reverse course on policy toward Iran—and to seek to sway its allies’ policies. A Democratic president and Congress could take a harder line on Iran, given that Democrats have joined Republicans in questioning the Administration’s decision to delay new sanctions on Iran for its recent ballistic missile tests.

Iranian officials have planned to start the bidding process on oil projects in March—and they still may hold to this timetable. They also likely will draw some participants—Russian, Chinese, and Indian companies among others. They too, however, may tread carefully.

Much Ado About Something? Or Nothing?

The next several months should prove interesting, volatile, and tense for oil producers, investors, and consumers. Markets will be waiting to see whether Oil Minister Zanganeh can deliver on his claim that Iran can add an incremental one million barrels to its crude export in the course of 2016, as well as for the Iranian government to prove it can attract substantial foreign investment to its oil industry.

The fortunes of producers, investors, and consumers rest on the answers to these questions.

This article originally appeared on Oilprice.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com