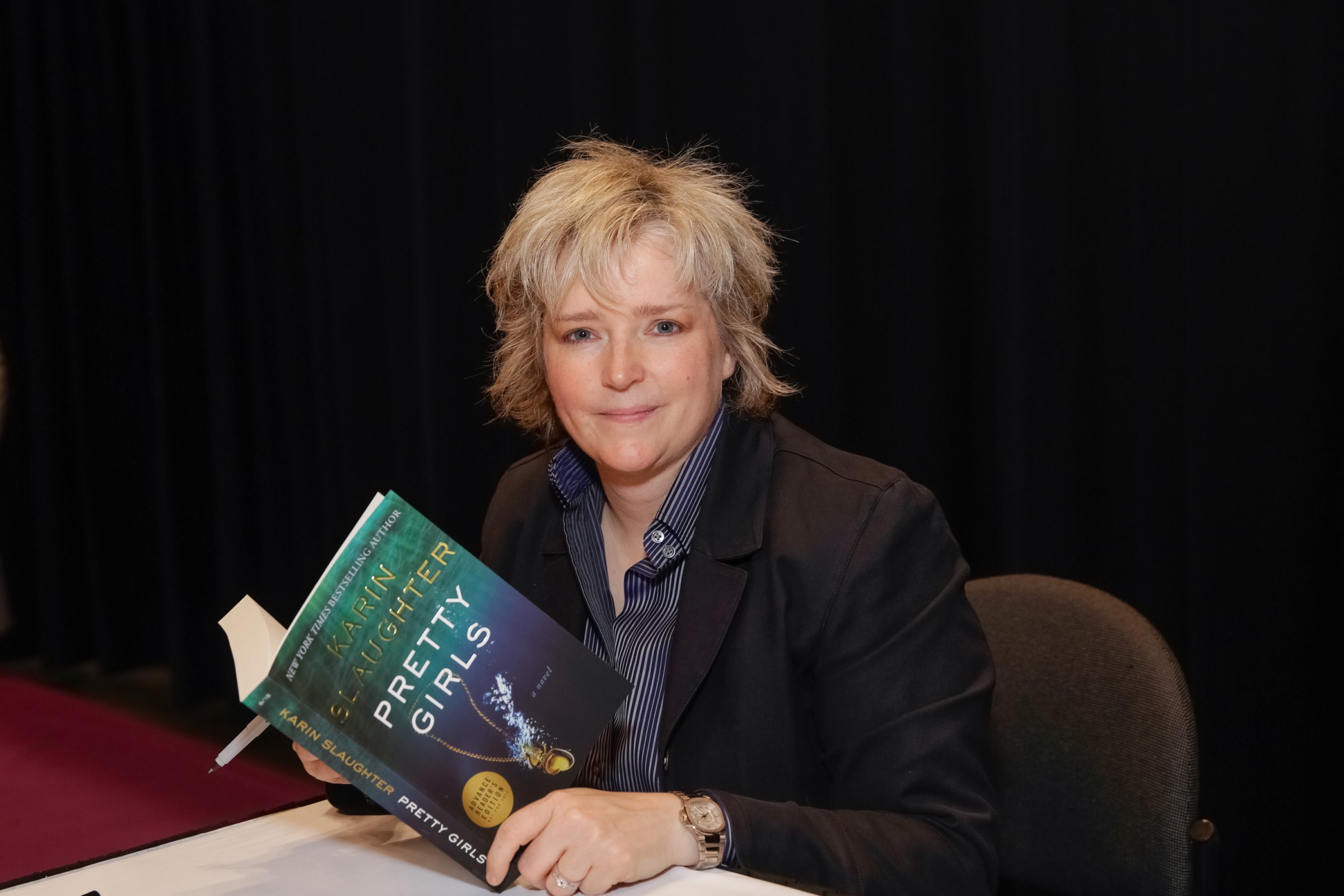

Karin Slaughter is an author of more than a dozen novels, including the Will Trent and Grant County series and the standalone novels Cop Town and Pretty Girls.

Several years ago, I was invited to tour the police museum at Scotland Yard where, among other things, they keep evidence relating to the Jack the Ripper investigation. Written within the margins of an old book is the apparent identity of the Ripper, recorded by the chief investigator of the case. Let me repeat that: Scotland Yard may already know the identity of Jack the Ripper. When I asked the museum director why the general public still considers the Ripper case unsolved, he shrugged and said: “People love a mystery.”

The man should be forgiven his understatement. People don’t just love mysteries. They are obsessed with them—especially the kind that are never definitively solved. This unabashed interest in crime is not just a peculiar trait of the English-speaking public. People all over the world have gotten swept up in documentaries like the first season of Serial and, more recently, Making of a Murderer.

Crafting a piece of gripping, narrative true crime that engages the world is not that different from crafting a piece of crime fiction. Here is the basic formula: An attractive young victim. A sexual component. Some form of social deviance. A zealous cop and/or prosecutor. A false confession. An alternative suspect. An injustice. A good guy. A bad guy. A name that instantly identifies the crime and the mystery. Lizzie Borden. Casey Anthony. O.J. Simpson. Amanda Knox. The West Memphis Three. Adnan Syed. Steven Avery.

Before I continue, I want to name Teresa Halbach, the 25-year-old whose burned remains were discovered on Avery’s land. One of the great travesties of this type of narrative is that the focus quickly turns away from the victim. (A travesty oft-repeated; homicide is one of the leading causes of death for women in Halbach’s age group.)

There are enough posts that toss around theories about Avery’s and his nephew, Brendan Dassey’s, respective guilt or innocence, but as someone who has made it her vocation to study the ins and outs of law enforcement and the justice system, what interests me most about the public’s reaction to Making a Murderer is the tendency to treat Avery and Dassey as outliers. Anyone who has spent any time in a courthouse can tell you that the two men typify the accused: uneducated, unsophisticated and perhaps most damning of all, under the poverty line.

To quote Steven Avery: “Poor people lose.” This is the only piece of the case that is not a mystery. Brendan Dassey joins the more than 60% of prison inmates who are functionally illiterate. As for his first court-appointed lawyer and so-called investigator: he got what he couldn’t pay for. During his trial, there was no money to pay experts on false confessions or psychiatrists to testify about Dassey’s lack of cognitive abilities. If you think experts wouldn’t have tipped the scale, just ask Ethan Couch, who confessed to killing four people, how his affluenza is treating him.

Lack of money isn’t just a problem on one side of the courtroom. The most important lesson I have learned from spending years talking to law enforcement officers is that the vast majority of them really want to do a good job. They have a physical need to do a good job. And yet, we don’t give them the resources that would help them. Effective police forces from big cities to small (especially small) require rigorous, continual training. Crime scene techs need constant scientific education. Prosecutors and public defenders deserve to make a living wage. There are massive backlogs of untested rape kits and DNA samples sitting in storage rooms all over the country. There are state labs that are withering away from lack of funding. That the system still works at all is a testament to the strength of character of the women and men who fill these thankless jobs. But sometimes, as in Dassey’s case, we the American public are getting what we won’t pay for.

This is where the final component of a good narrative comes in: the sense of a great injustice. No matter where you stand on the guilt or innocence of Avery and Dassey, it would be very hard to deny that improprieties—some great, some small—have gone on in Manitowoc County. Evidence was mishandled. Crime scenes were trampled. The chain of custody was broken. Procedures were ignored. To me, this is the real mystery at the heart of Making of a Murderer—not “did they do it?” but “are we going to allow the government to cheat?”

We don’t need Making a Murderer to tell us that the government doesn’t always play by its own rules. Many of us feel like we are the Dasseys while others get to be the Couches. In a democracy, that’s the puzzle we should be obsessed with solving: how do we make the system work for everybody instead of focusing such a massive amount of energy trying to make it work for just these two people? Don’t get me wrong. New trials for Avery and Dassey would be a tremendous accomplishment, but properly funding all sides of our criminal justice system could go a long way toward preventing future wrongful convictions. Of course, that would take more than signing an online petition or posting alternative theories on Reddit. Real reform would take money. It would take leadership. It would take action. Thinking back to my tour of Scotland Yard, maybe people don’t want a solution after all. They just want to love the mystery.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com