Since its inception, photography has been inseparable from the world of politics, where image is crucial. For most presidential candidates, controlling that image has become essential to their message. In a series called Seeing Politics, TIME LightBox examines political photography throughout the 2016 campaign in profiles, features and analytical pieces.

In 2016, it is almost unthinkable to imagine a photographer could reinvent their career by making black-and-white documentary pictures, but that’s precisely what Mark Peterson did with a project he calls Political Theatre. At a time when we continually hear American voters say they support candidates because they’re looking for an “outsider” and they’re less interested in “professional career politicians,” perhaps political photography also needs an outlier to get our attention?

Peterson began pursuing a newer cinematic style after being inspired by the Orson Welles classic Citizen Kane. Using the same tools most nonprofessionals use — Instagram, a few cheap phone apps and a handheld flash — Peterson spent the past few years on the road documenting the often fraught and bifurcated American political landscape.

A photographer since 1980, Peterson came to the profession late at age 29 after a series of menial jobs doing everything from working in a warehouse to bartending. He began his journalism career at a local newspaper where he was actually delivering papers. “And within a month,” he says, “everybody quit, and I was the editor. It wasn’t a very pretty sight, but I got a taste of journalism.”

Eventually he began working for an alt-weekly in Minneapolis called City Pages, where he began to take pictures. Later as a stringer for UPI he shot a photo of then-presidential hopefuls Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro that ended up on the cover of the New York Times, and from there he kept going. “I think then — and even now, I’m politically naive and I don’t really know politics,” he tells TIME. “Walter Mondale in 1984 was pretty much my first time seeing the mechanism of politics and the whole carnival of everybody getting on a bus and following the candidate.”

A decade later, in 1991, when David Duke ran for governor of Louisiana, he learned an important lesson. “You look at David Duke, who was a former clansman and an avowed racist, and he looked like a normal person,” he says. “He looked like Robert Redford looked in The Candidate, a perfect candidate. You could never, in a still picture, capture the anger and how racist he was. The only way to do that was to look into the audience and how riled up they were by his message.”

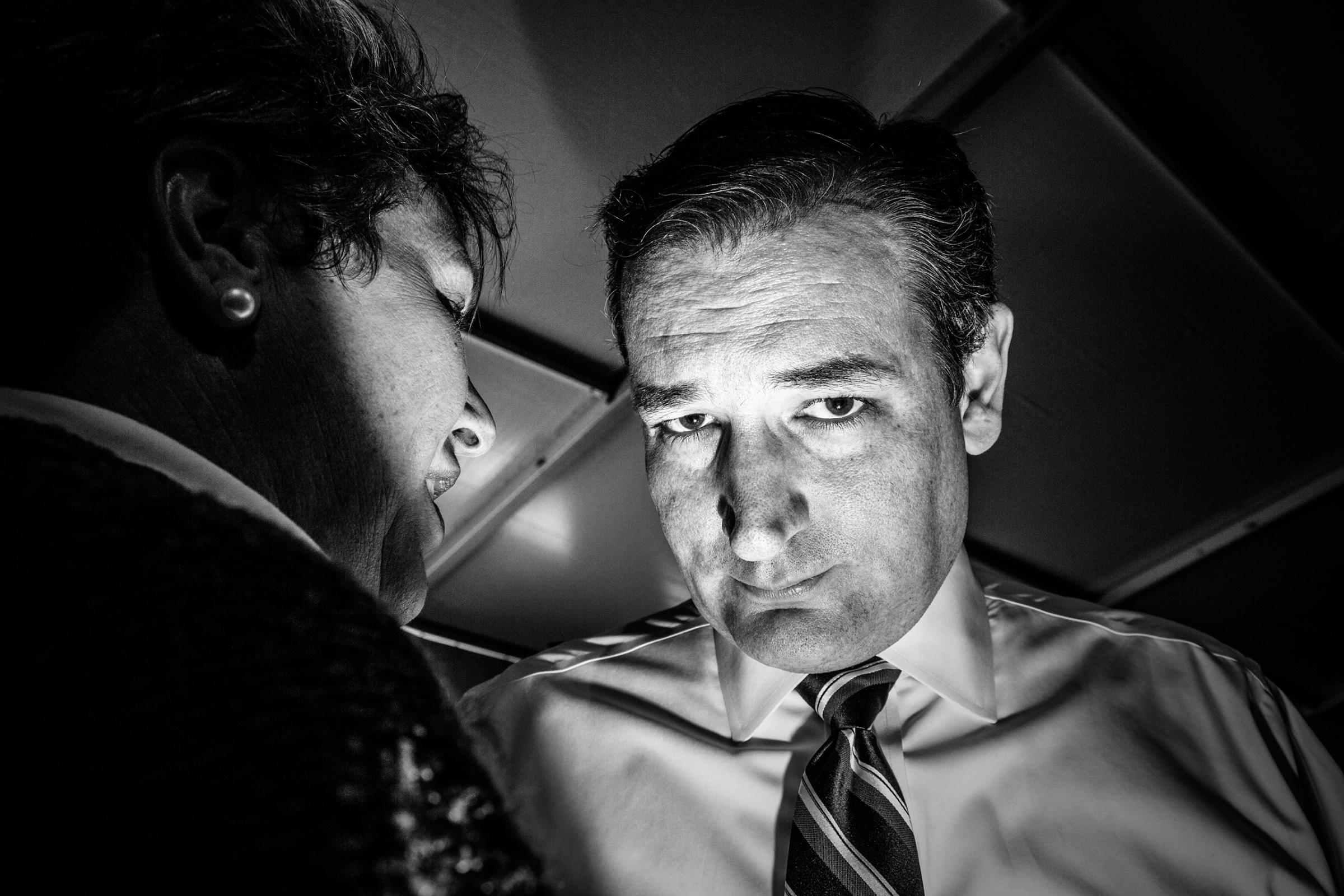

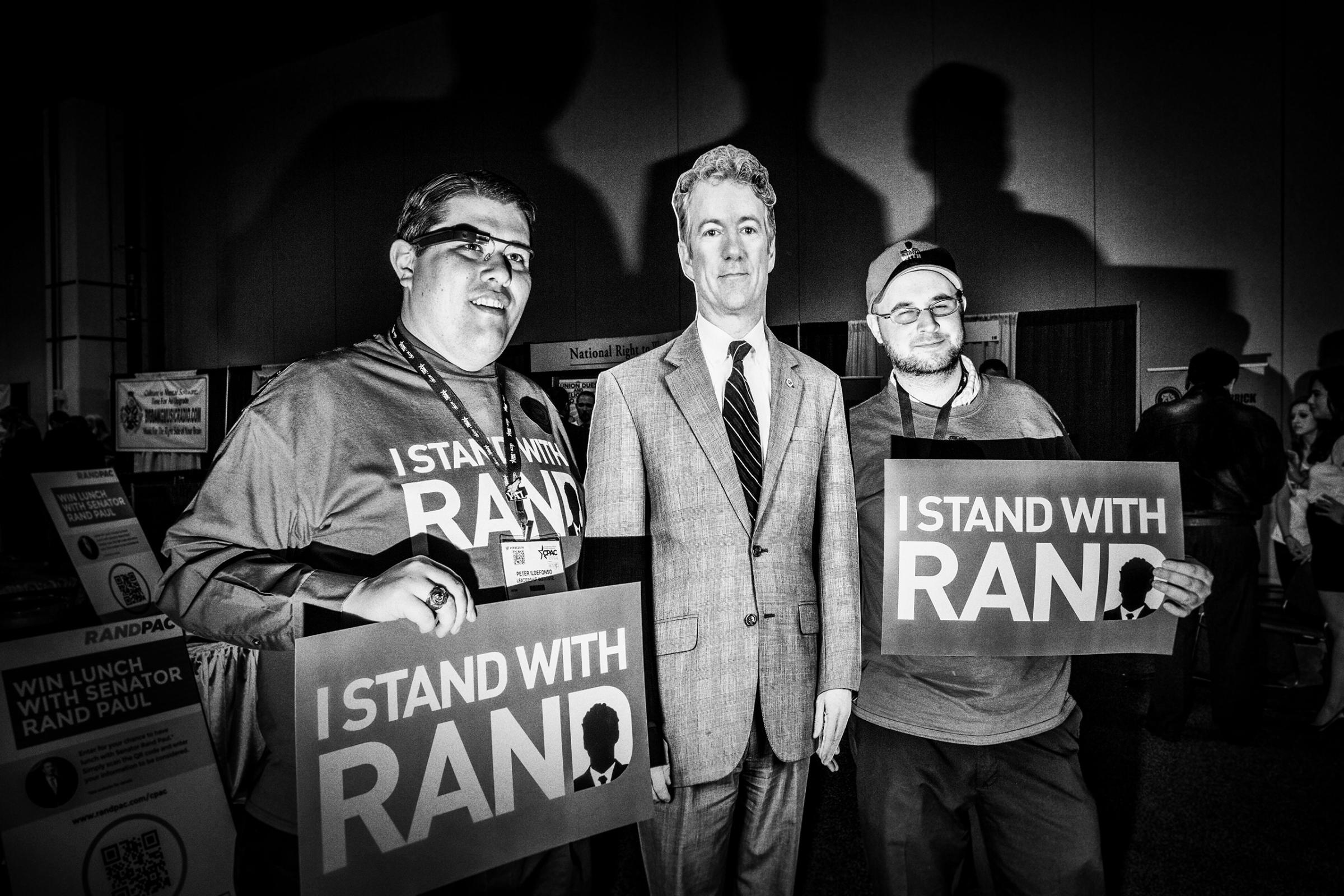

Peterson’s signature approach to a photo shoot typically sidesteps the main event and takes you somewhere unexpected to tell a story. For example at an NRA rally in Alexandria, Va. (slide 15), instead of showing just the speakers, he captures Americans’ right to bear arms in the bathroom by shooting two men at a row of urinals with large rifles strapped to their backs. One of his more recent images, featured on last week’s cover of TIME magazine, shows a rear-view shot of Donald Trump as he swoons a massive crowd in Rochester, N.H. It’s a sea of captivated faces staring back at the camera. “The candidates are all very polished in how they look,” Peterson says. “They practice for days not to make a mistake. But when you look at their audience, it’s usually much more revealing.”

“The genesis of Political Theatre started in September of 2013,” he says. “Obamacare was just about ready to be enacted, and Congress was going to try and stop it. There was even talk of shutting down the government over it, which they did.” He attended a Tea Party rally outside the steps of Congress, and that was the moment of inspiration for this work. “It was just a TV-orchestrated event,” Peterson says. “And I took these pictures and when I processed them, I was actually really unhappy. They didn’t capture any of that. I didn’t feel like they showed how fake the event really was, that it was just done for sound bites. One sound bite after another.”

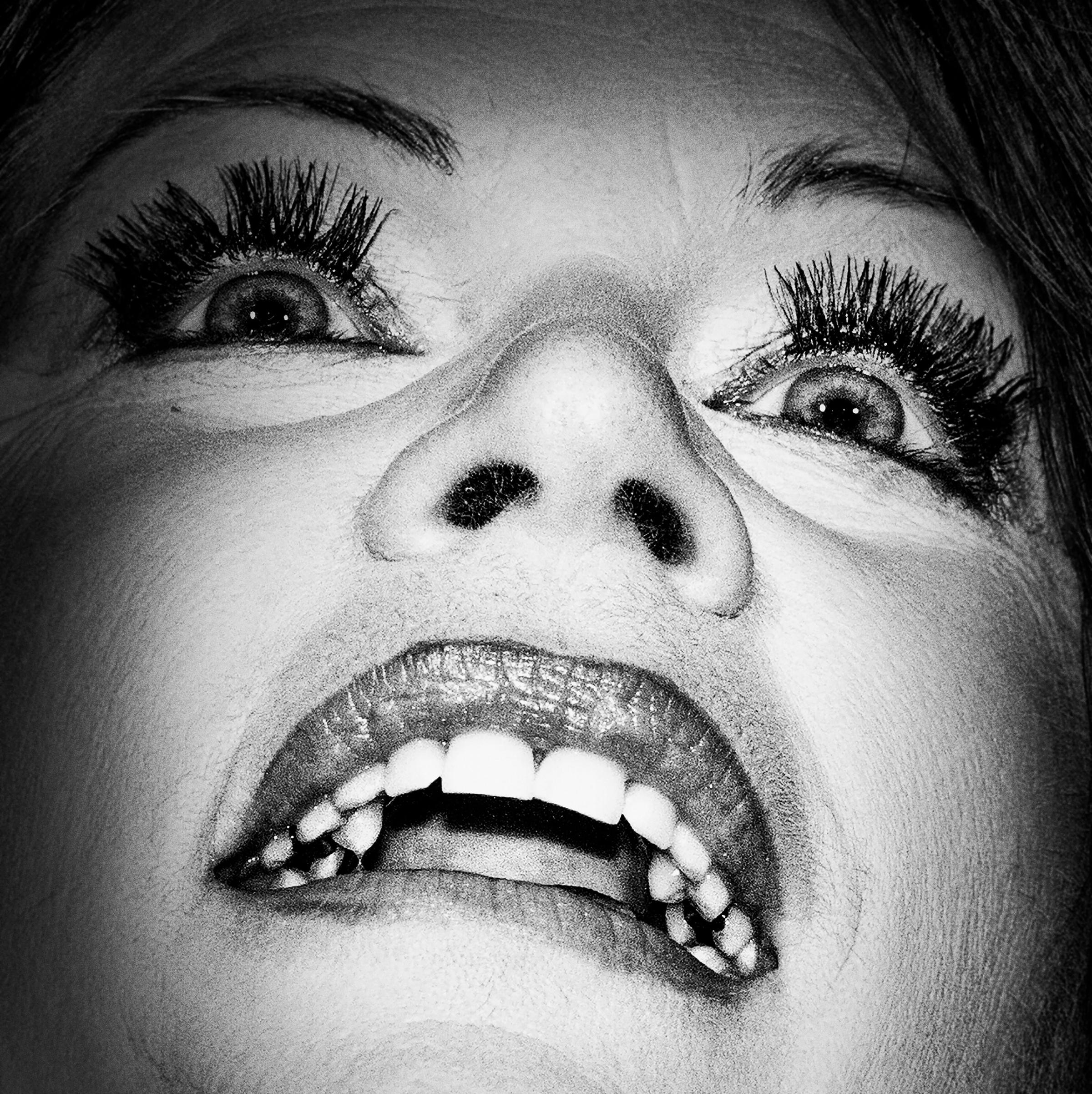

When photographing Republican presidential candidate Chris Christie, Peterson was fascinated with the politician’s mouth. “I went to an event, and all I wanted to do was just photograph his mouth because, really, that is him,” he says. “I’ve photographed him in the past and made pictures of him yelling at people in town halls but they didn’t really show the bare crux of what he is, or what his power is as a politician, which is his ability to just shout down anybody else’s opinion.”

Trying to distill things down to their essence or symbolically is a technique Peterson often employs while thinking more conceptually on how to communicate what defines a politician and what they stand for at the moment. “I don’t want to be so locked in to an idea that I miss everything else,” he says. “I’m always trying to distill it, we’re making an editorial judgment every time we push the shutter or edit.”

“I go Blood Simple when I shoot,” says Peterson, referring to the 1984 Joel and Ethan Coen movie about a private detective. “I just keep shooting and shooting, and I’m sure I look like a crazy person. But I never feel comfortable that I have the shot.”

Peterson publishes almost all his work through Instagram, where he says he creates a virtual “proof sheet” for a community of followers to comment and share his work. In the slurry of our carefully curated, self-promotional lives (and now too many ads), Peterson’s photographs manage to feel surprising and reveal a live stream of the political circus as he sees it.

The flash freezes politicians in grotesque expressions distilling moments of cinematic horror and absurdity that his Instagram followers Like over and over again. “For politicians, the flash is like crack,” he says. “It makes things more kinetic. I think anybody that comes into a room and suddenly there are flashes going off, they’re going to be much more alive. I like that it gives more dimension and depth to the work.”

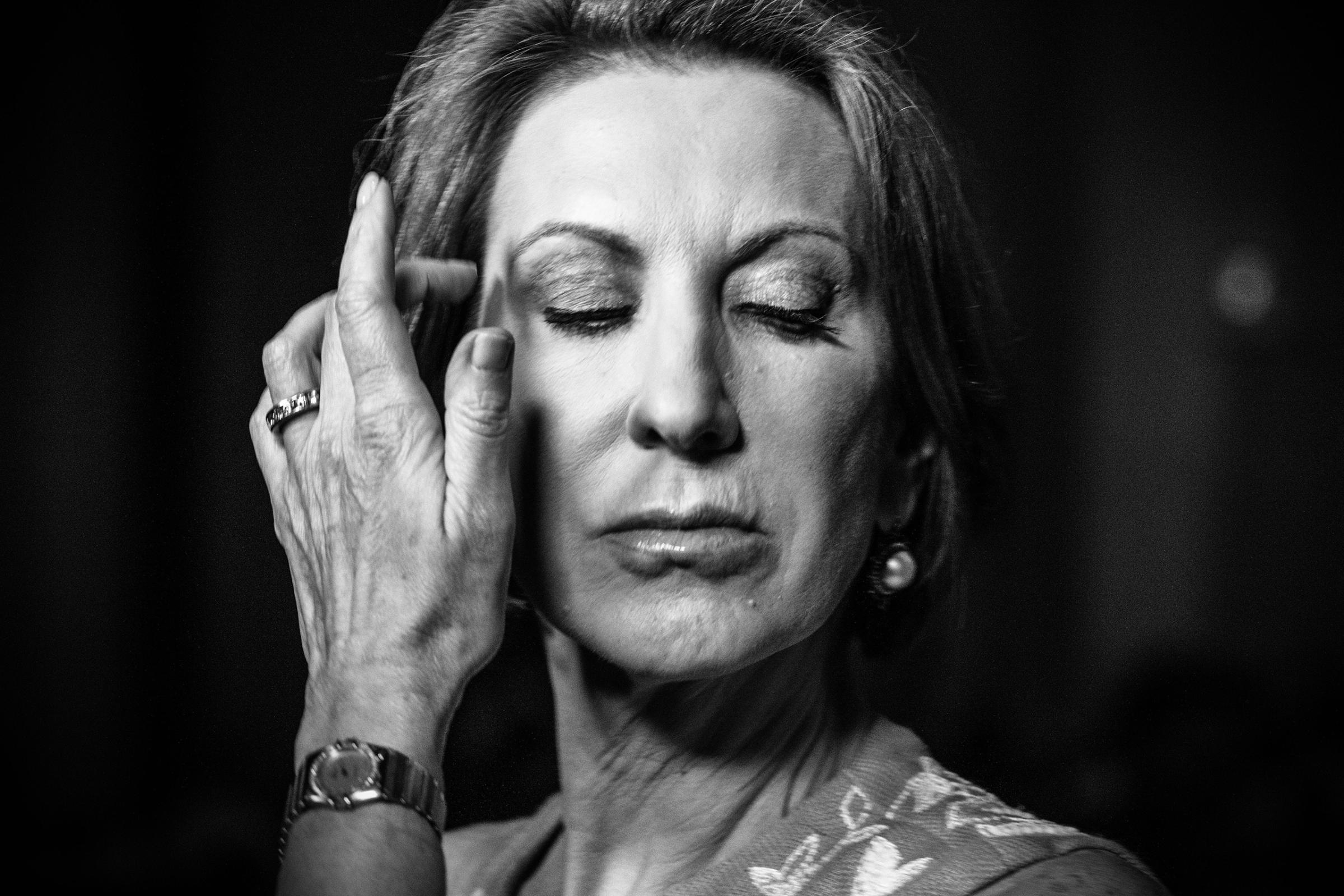

The popularity of Peterson’s pictures may be explained by the delight we feel of seeing familiar figures through such a stylized lens but within the massive project more subtlety is revealed. Under his handheld flash, he shows candidates as human beings with their flaws and imperfections amplified by his careful lighting and framing.

The texture and toning of his work is also essential to his style. “I’d shoot pictures with my DSLR, but then I’d put them into my cellphone, and I’d use every 99¢ app I have to just destroy them,” he says. “I’ve always adhered to some of the tenets of photojournalism, but it kind of changed for me. What are these rules? I’m not manipulating images, but maybe I’m manipulating tones and making it dramatic.”

Using cheap apps to create something singular works against the popular notion that everybody is a photographer these days. “I’ve never been a very technical person,” he says. “I’ve never been good at Photoshop, and that’s why I started using the apps because I could just hit a button and it would be like, yeah, that’s how I want it to look. Instagram was a really nice way of starting to put the work out, and I think it is a real proof sheet of people’s work. The John Stuart Mill thought that you just throw it out there and let people start thinking about it.”

Peterson’s decision to publish his photographs on Instagram allowed him to be noticed by editorial clients such as New York magazine, Politico and MSNBC. “Running the pictures in so many places was directly related to Instagram,” he says.

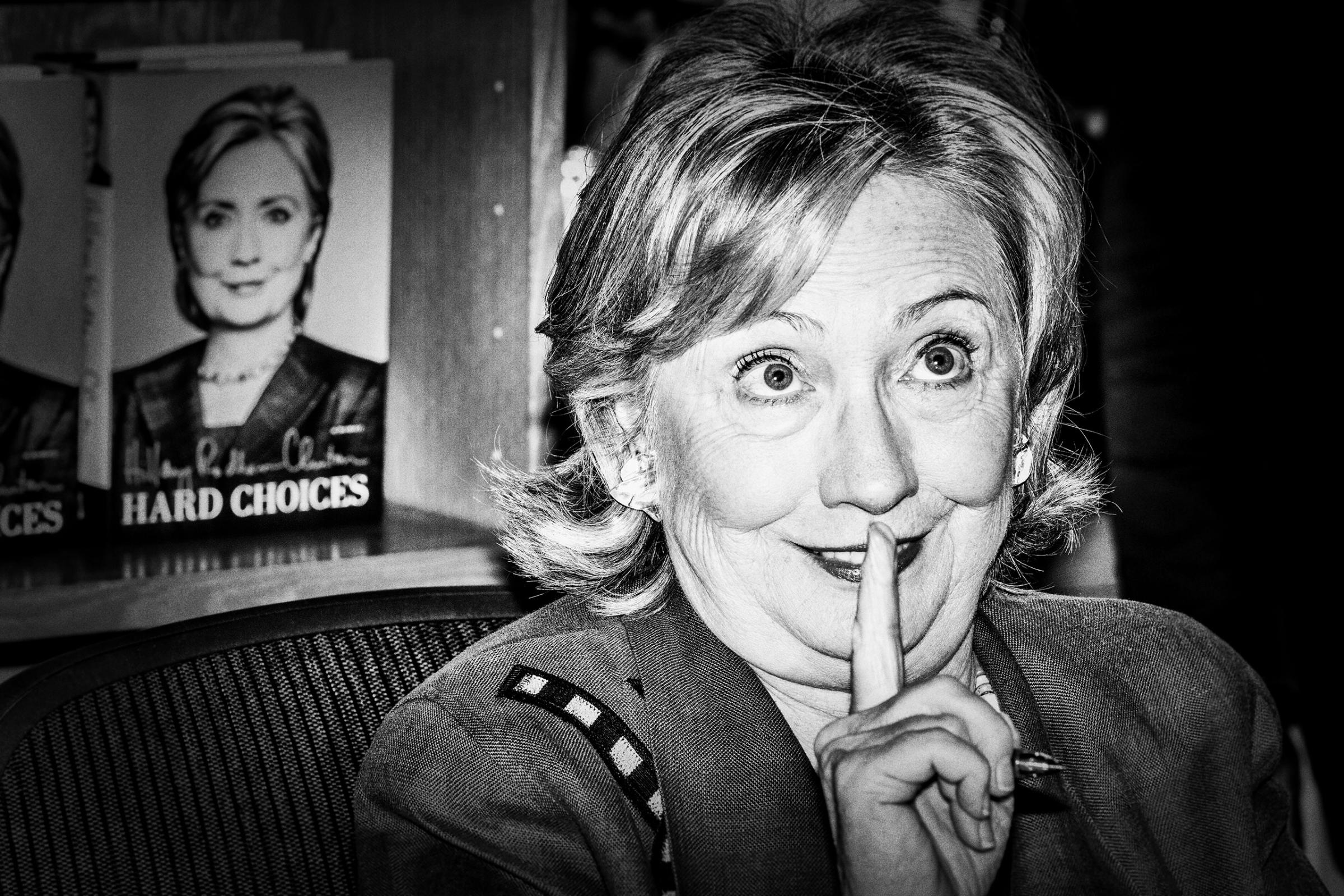

Of course, his photographs can, at times, be controversial with his followers and readers of the various magazines he works with. “I think people go both ways with the images,” he says. “Some people laugh at them, and some people think that they’re very mean. I have friends who are conservative, who say, ‘Well, what about the Democrats?’ I think my Hillary picture may be one of my most surgical pictures [I’ve made]. I think it captures her in a moment that you’re just not used to seeing her. You’re used to seeing her look very confident. Very — very self-aware at all times. I think there’s probably nobody that is more aware of the press than Hillary Clinton and the pitfalls that come with the press.”

“I’m not criticizing anybody,” he says. “But the other pictures are the pictures the campaign wants you to take. Everything is designed for that one perfect shining light on that candidate and there’s enough of those pictures being taken.”

Mark Peterson is an award-winning American photographer represented by Redux Pictures in New York. He is a regular contributor to TIME, MSNBC, New York magazine and Politico. You can follow his Political Theatre project on Instagram @markpetersonpixs.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @paulmoakley.

Read more stories from TIME LightBox’s Seeing Politics series.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com