In the mid-1930s, the celebrated cartoonist William Steig (1907-2003) – who was then regularly freelancing for The New Yorker, and would later go on to author a vast array of classic children’s books, such as Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, the Doctor DeSoto series, and Shrek!, amongst many others – became profoundly interested in the writings of Sigmund Freud.

Deeply inspired by psychoanalytic theory, Steig began to produce a series of what he himself called “symbolic drawings”, which aimed to portray people in the throws of various emotional and psychological states. The drawings, often quite Cubist in style and accompanied by simple yet heartrending captions such as “I want your love but don’t deserve it”, “People are no damned good”, and “All I ask is to be left alone”, were in a sense an attempt to introduce the complexity of repressed feelings, internal tensions, and hidden yearnings into a medium that was primarily visual, and generally associated with lighthearted humor and wit rather than intensive soul-searching.

Boston

Unsurprisingly, when The New Yorker’s founder and editor at the time, Harold Ross, initially saw the works, he deemed them “too personal and not funny enough.” Nevertheless, Steig remained undeterred, and several years later collected his “symbolic drawings” together into book form, releasing them as three volumes – About People (1939), The Lonely Ones (1942) and All Embarrassed (1944). The Lonely Ones in particular – with its depictions of quiet yet powerful moments of existential crisis – brought Steig wide acclaim, and remained in print for nearly three decades; today it represents one of the earliest and most important publications within the genre, specifically in terms of aiming a book of cartoons exclusively at an adult audience.

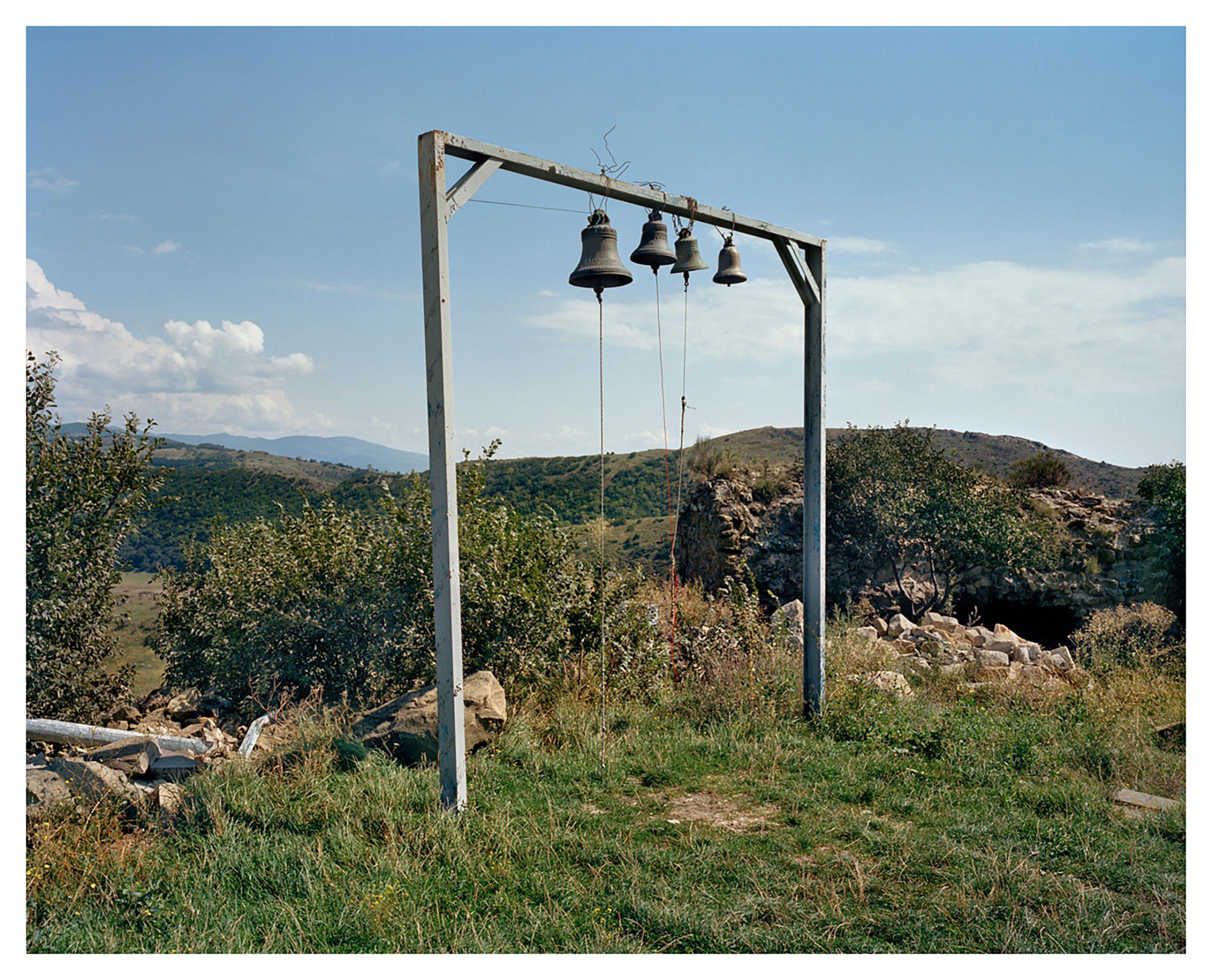

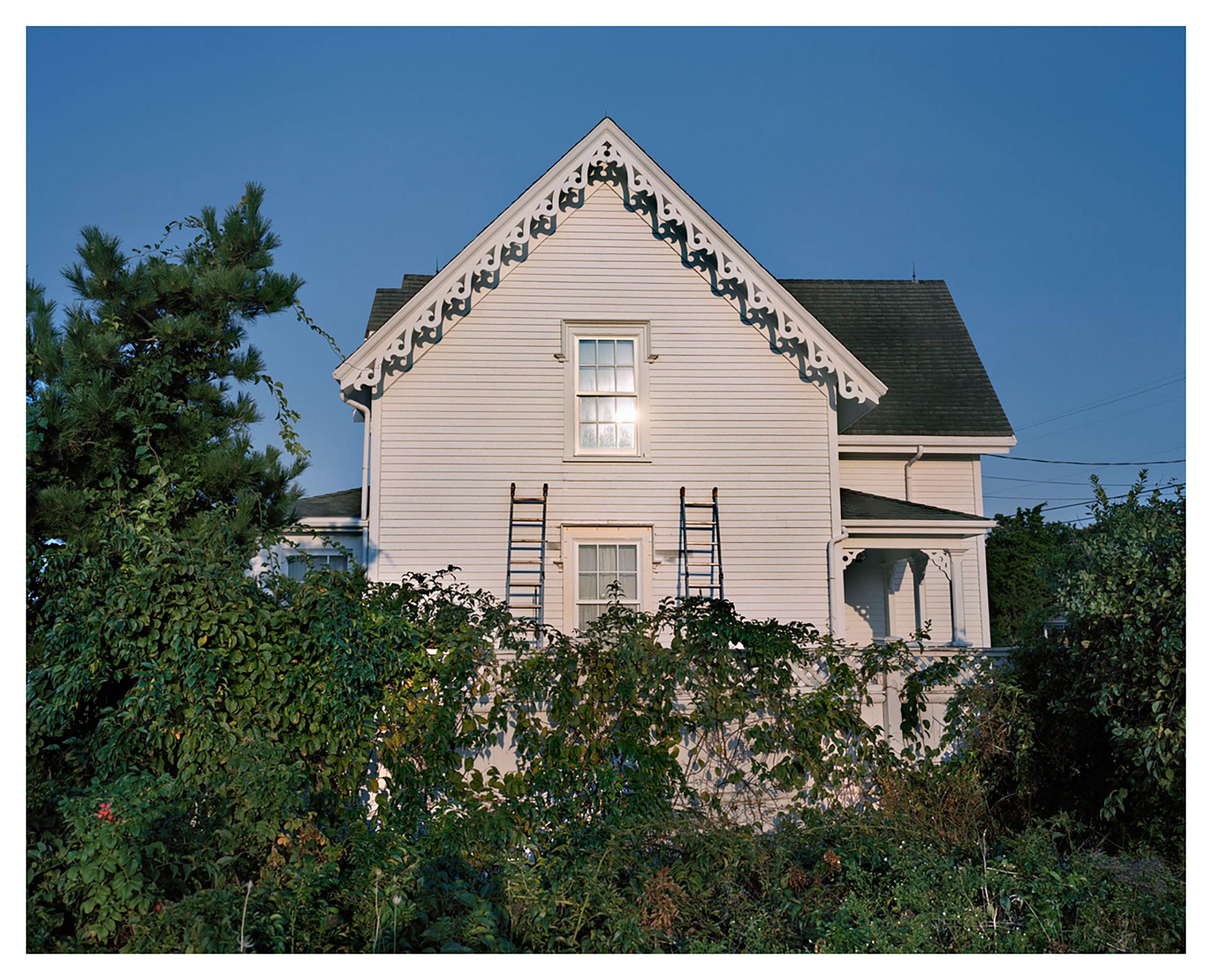

Earlier this year, the photographer Gus Powell – who himself regularly freelances for The New Yorker today – released a perfectly pocket-sized publication that not only directly borrows Steig’s title, but also draws inspiration from Steig’s approach in a variety of very effective and compelling ways.

Also entitled The Lonely Ones (published by J&L Books), Powell’s book – like Steig’s – pairs succinct texts with his photographs in a manner that is suggestive of an underlying internal dialogue; between the author and the reader, or perhaps between the author and himself. The book is designed so that on each page the reader first encounters one of Powell’s suggestive one-liners on its own, and then discovers a curiously captivating image hidden within a gatefold behind it. The unsettling plea, “Let’s not ruin it by talking,” opens to reveal a standoff between a fashionable young woman and a lonesome horse on the streets of New York, their respective chestnut ponytails mirroring one another as they catch in the late-afternoon sunshine. The unexpected query, “Which way to the symposium?” conceals a passing instant on a perfect summer’s day, where up in the deep-blue sky an enchanting monarch butterfly silently flutters by. The single statement, “Yes”, leads into a sandy beach swathed in fog, where three officious figures stand at the shoreline pointing crimson smoke-bombs out to sea, perhaps in the hopes of retrieving lost sailors, and at the same time making a vividly evocative offering to the vast ocean before them.

Photographs such as Powell’s, which are in fact strengthened and made meaningful by their open-endedness and the curiosity it inspires, are often stifled if not strangled when matched with accompanying captions or texts; words often divulge such images’ secrets too easily, transform their mysteries into something more literal or illustrative, or pin them down to specific circumstances, meanings or intentions. Yet, like Steig, Powell performs this balancing act between text and image masterfully, using sparse sentences to invoke and enhance the symbolic power of his imagery – to pry his photographs open even further, uncover their potential for both emotional and psychological insight, and infuse them with a subtle yet very personal sense of poignancy that is at once both playful and profound.

Gus Powell is a photographer based in New York. His show, The Lonely Ones, is on view at the Sasha Wolf Gallery in New York until Feb. 26.

Natalie Matutschovsky, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s senior photo editor.

Aaron Schuman is an artist, writer, curator, and lecturer, and the founder of SeeSaw Magazine.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com