On change.org, more than 300,000 people have signed a petition demanding that Steven Avery, a convicted murderer, be released from prison. The Wisconsin man, the petition argues, was the victim of “unconstitutional mistreatment at the hands of corrupt local law enforcement”; accordingly, his trial should be thrown out and he should be “exonerated at once by pardon.”

But the impetus for these demands isn’t the discovery of new evidence or the revelation of a secret witness. It’s a 10-episode docuseries on Netflix.

Making a Murderer is part of a new wave of interactive true-crime entertainment. Whereas Nancy Grace openly fries her subjects and Dateline wraps messy trials into snackable segments, this breakout series–like the podcast Serial and HBO’s The Jinx before it–explores a single story over multiple episodes. That structure allows creators to present all the relevant components of a case, they say, and let viewers draw their own conclusions. “We weren’t there to solve the crime. We were there to document the experience of being accused in this country,” Murderer co-creator Moira Demos has said. “We’d always hoped the series would promote a dialogue.” In other words, this isn’t just a TV show. It’s a call for social justice.

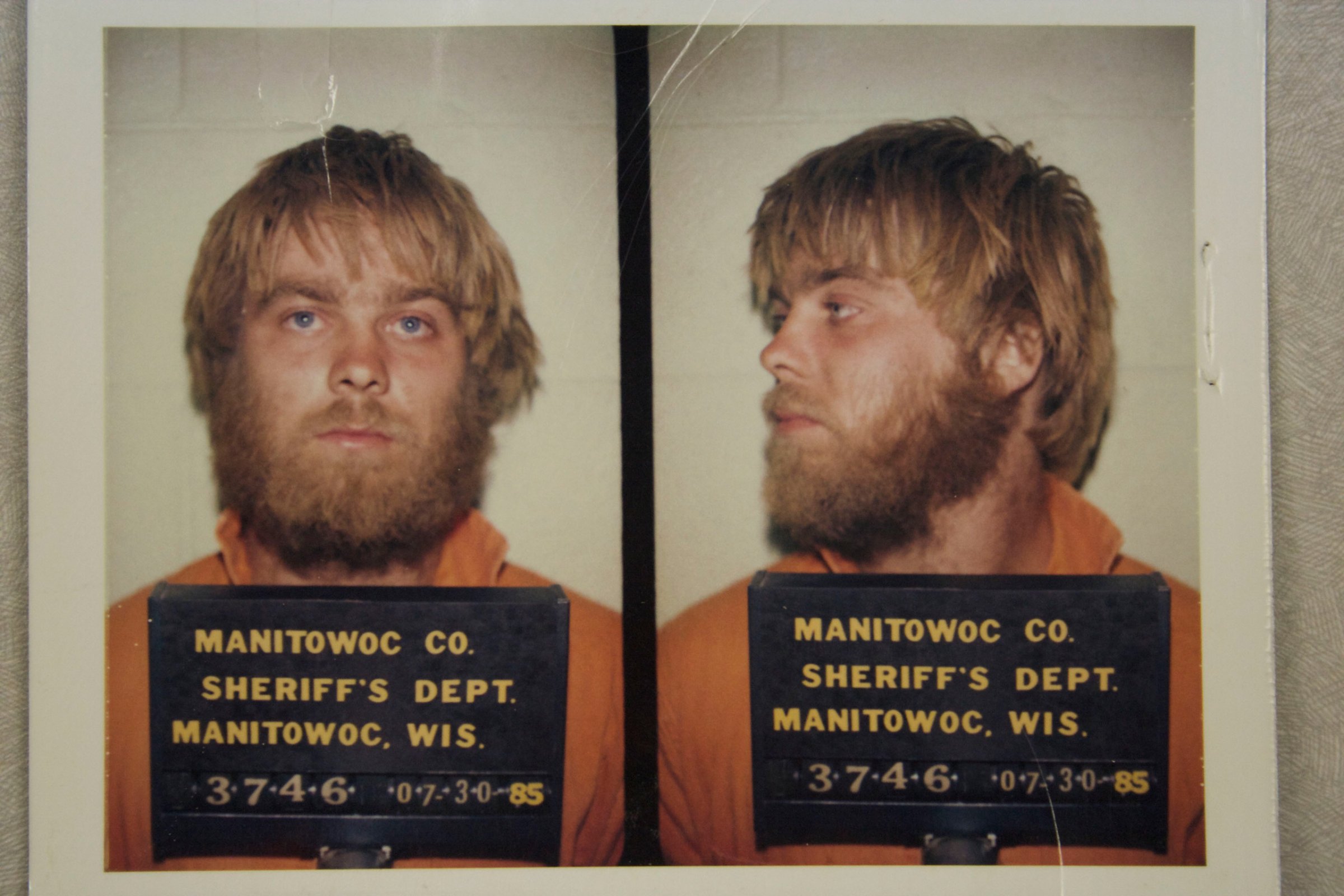

By that measure, Murderer is remarkably effective. We meet its subject, Avery, as a folk hero who has just been released from prison after serving 18 years for an assault he did not commit. (He’s freed by DNA testing.) Two years later, Avery gets arrested for murder by the same cops he’s suing for negligence–and using a mix of media clips, trial footage, narrative title cards and original interviews, Demos and co-creator Laura Ricciardi recount the shadowy events that lead to his conviction, one episode at a time. It’s both enthralling and enraging.

But is it accurate? In some ways, yes: everything depicted on the show actually happened. Yet at its core, Murderer is still a reality-TV series. That means central figures are “cast” in roles (hero, villain, victim) and its events are heavily edited to ensure that viewers know who’s who, just as they would on an episode of Survivor or The Real Housewives. That’s the nature of condensing more than 30 years of legal drama into 10 episodes. Nonetheless, it has given rise to one of the sharpest critiques of Murderer so far: Avery’s prosecutor, Ken Kratz, alleged that the show left out crucial facts to advance a pro-Avery agenda, a sentiment echoed by several Internet sleuths. (Demos and Ricciardi deny those claims.)

None of which means fans aren’t allowed to feel angry or sad or even determined to fight for change. Although the true-crime genre may have started with chilly, removed storytelling, as in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, there’s a reason the melodrama of Murderer and Serial is resonating right now. A growing number of people sense “that the American judicial system has serious problems,” says David Schmid, an associate professor of English at the University of Buffalo who has written extensively about the cultural impact of true crime. “These shows give them a way to work through their feelings about that.” Errol Morris, director of the documentary The Thin Blue Line, says true-crime fans are drawn to “the belief that through investigation and ratiocination we can come to a conclusion about the world.”

Still, true-crime characters are real people, and acting out against them on the basis of a set of highly curated facts can be ill-advised if not harmful. According to Jay Wilds, a key figure in Serial’s Season 1 case, the podcast’s fans have videotaped his house and posted his personal information on Reddit. And in the days following Murderer’s premiere, the Yelp page for Kratz’s law firm was inundated with negative reviews, including a re-airing of embarrassing indiscretions unrelated to his prosecution of Avery.

Dean Strang, one of Avery’s lawyers, has said this vitriol reminds him of what he faced in 2005 when the public became convinced his client was guilty after watching local news reports. Now that Strang is being praised, however, he’s just as skeptical of the sentiment. “Both of those experiences are artificial and distorting,” he has said, because they represent only “what’s going on in fevered social media”–not what actually happened, in the courtroom or in the case.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com