Marco Rubio has summed up the concerns of many Americans when it comes to taking action against climate change. “Every proposal they put forward,” he said during a campaign debate this fall, “will make it harder to do business in America. Harder to create jobs in America.”

That perennial worry—that reducing carbon emissions will prove too disruptive for the nation’s economy—is a frequent refrain among those opposed to action, and a legitimate question for climate activists: How can an economy built on fossil fuels prosper in a post-fossil-fuel world?

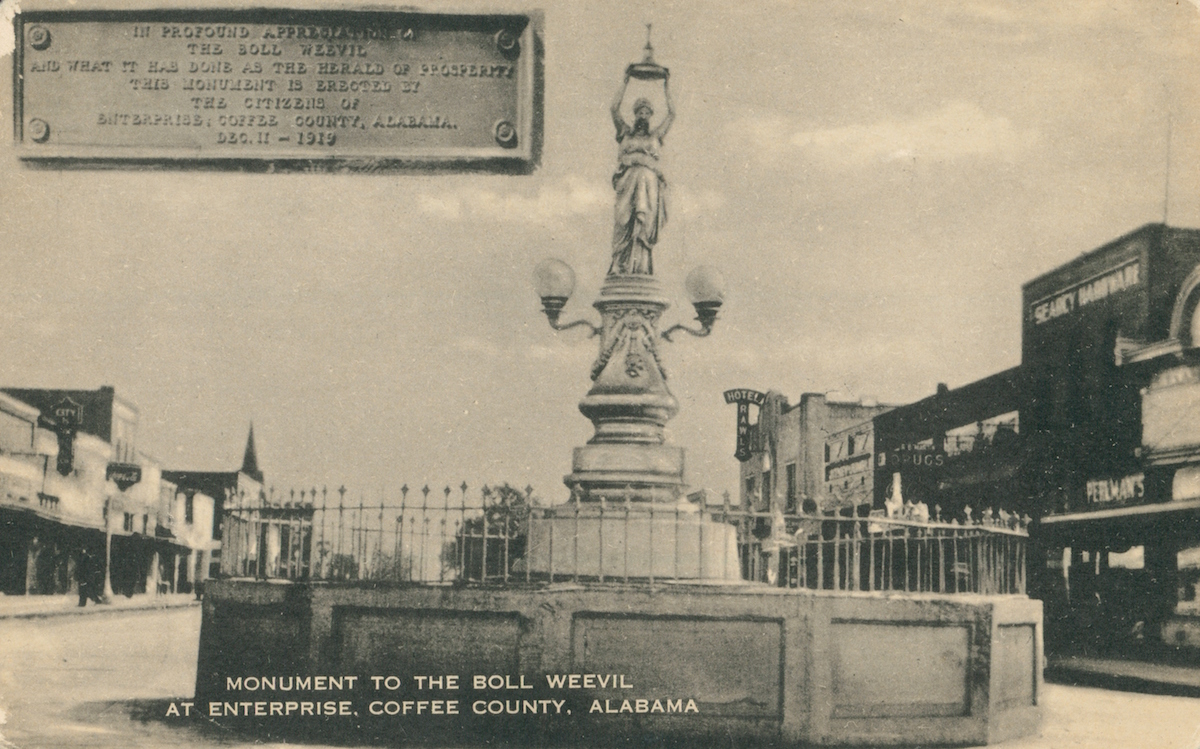

One answer might be found in the small town of Enterprise, Ala., where an unusual monument tells the story of another environmental crisis, and of the leaders who overcame it.

There, a statue stands at the intersection of College and Main: a slender lady in flowing white robes, a heavy object held high above her head. Think Charlton Heston in that scene from the Ten Commandments—only where Moses held stone tablets, our lady holds an outrageously oversize bronze beetle.

The beetle is the boll weevil, Anthonomus grandis, an agricultural menace that destroyed cotton crops here a hundred years ago, ravaging the area’s economy and taking its farmers to the edge of ruin. It’s also the town’s hero, the six-legged savior that put Enterprise on a new path from stagnation to prosperity.

Boll weevils are voracious pests of cotton plants: each spring, adults emerge from hibernation to lay eggs within cotton bolls, the tissues that eventually give rise to the plant’s valuable fibers. As the eggs develop, they destroy that year’s crop quite literally from the inside out.

The weevils are, in short, a cotton farmer’s worst nightmare—a nightmare that came true for thousands across the South starting in 1892. That was the year the insect, a native of Mexico, first crossed the Rio Grande near Brownsville. The destruction that followed would eventually cut a path from Texas to Virginia.

For southern farmers, it couldn’t have come at a worse time. By 1910, the year the weevil first crossed into Alabama, the agricultural South had become addicted to cotton; growers couldn’t secure loans for land purchases without pledging every available acre to the crop. Meanwhile, ecological pressure from the plant’s intensive cultivation ruined soils, contributing to an unjust economic model based on tenancy and share-cropping.

Into this well-established order, the weevil came like a cannon shot. The outbreak became the object of intense public anxiety throughout the South; any insect spotted on a cotton plant was enough to spark a local panic. USDA officials called the invasion a “wave of evil.” Newspapers predicted the end of the southern way of life. Surely, the argument went, an economy based on cotton cultivation would crumble in a post-cotton world. Jobs would be lost. Businesses would fold.

In the midst of this fear, progressive reformers begged to differ, arguing that it was both possible and beneficial to change the way the economy worked. George Washington Carver—a former slave and the South’s foremost agricultural innovator—pushed for peanut-based crop diversification. Theodore Roosevelt touted the weevil as a “blessing in disguise,” a powerful incentive to adopt “scientific husbandry” across the region.

In Alabama’s wiregrass region, already a strange ecological fit for the cotton plants that dominated its economy, the choice soon became clear: respond proactively or suffer the consequences. By the end of 1915, the year the beetle was first spotted in fields near Enterprise, area farmers had lost 60% of their crop. Within months, a coalition of growers and businessmen arranged to scrap the next year’s cotton in exchange for peanuts.

The plan worked. By 1917, Enterprise was harvesting more peanuts than anywhere else in the nation. Peanuts led to value-added products like oil and nut butters, and the plant’s use as hog feed led to a robust market in meat processing. By 1919, town leaders were confident enough in their collective future to commission a cast-iron statue from Italy, a permanent monument to the boll weevil, Enterprise’s “herald of prosperity.”

While historians continue to debate the weevil’s regional legacy—southern cotton production actually increased after the outbreak, in part due to higher profits brought on by scarcity—there’s little doubt that the invasion opened new space for diversified agriculture. Enterprise stood at the vanguard of that change, proof that it was possible, in the face of impending disaster, to transform an economy completely.

Today this town of 26,000 is doing just fine. Surrounded by peanut farms, military installations, and manufacturing facilities, Coffee County’s largest community is among the most prosperous in this rural corner of a rural state. Visitors can still stay at the Boll Weevil Inn, a few blocks from the statue.

Just this past year, on the centennial of the weevil’s first foray into Enterprise, a bold new mural went up downtown. In the left panel, an anxious farmer looks out over a cotton crop darkened by storm clouds. On the right, thriving peanut plants grow tall under a clear, blue sky.

Between them, perched on a cotton boll, an unlikely hero turns its beady eyes to the future.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Ansel Payne is an Alabama-based naturalist and writer. He holds a PhD in Comparative Biology from the American Museum of Natural History.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com