During the annual Asia-Pacific leaders’ summit in Manila in November, President Obama sought out two people for a pressing conversation. Not Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose forces were busy changing facts on the ground in Syria, nor Chinese President Xi Jinping, whose global economic strategy is paying off for China. Instead, he turned to a pair of entrepreneurs: Jack Ma, the CEO of the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba, and Aisa Mijeno, an ecological innovator from the Philippines. Obama gave a short speech and then spent nearly half an hour moderating a panel discussion with two businesspeople.

Obama’s explicit message was that government and business must work together to solve energy and environmental problems. The unspoken message was louder: in a hotel filled with leaders, the President of the United States felt he had more to gain chatting with private citizens than engaging his counterparts. And he was probably right.

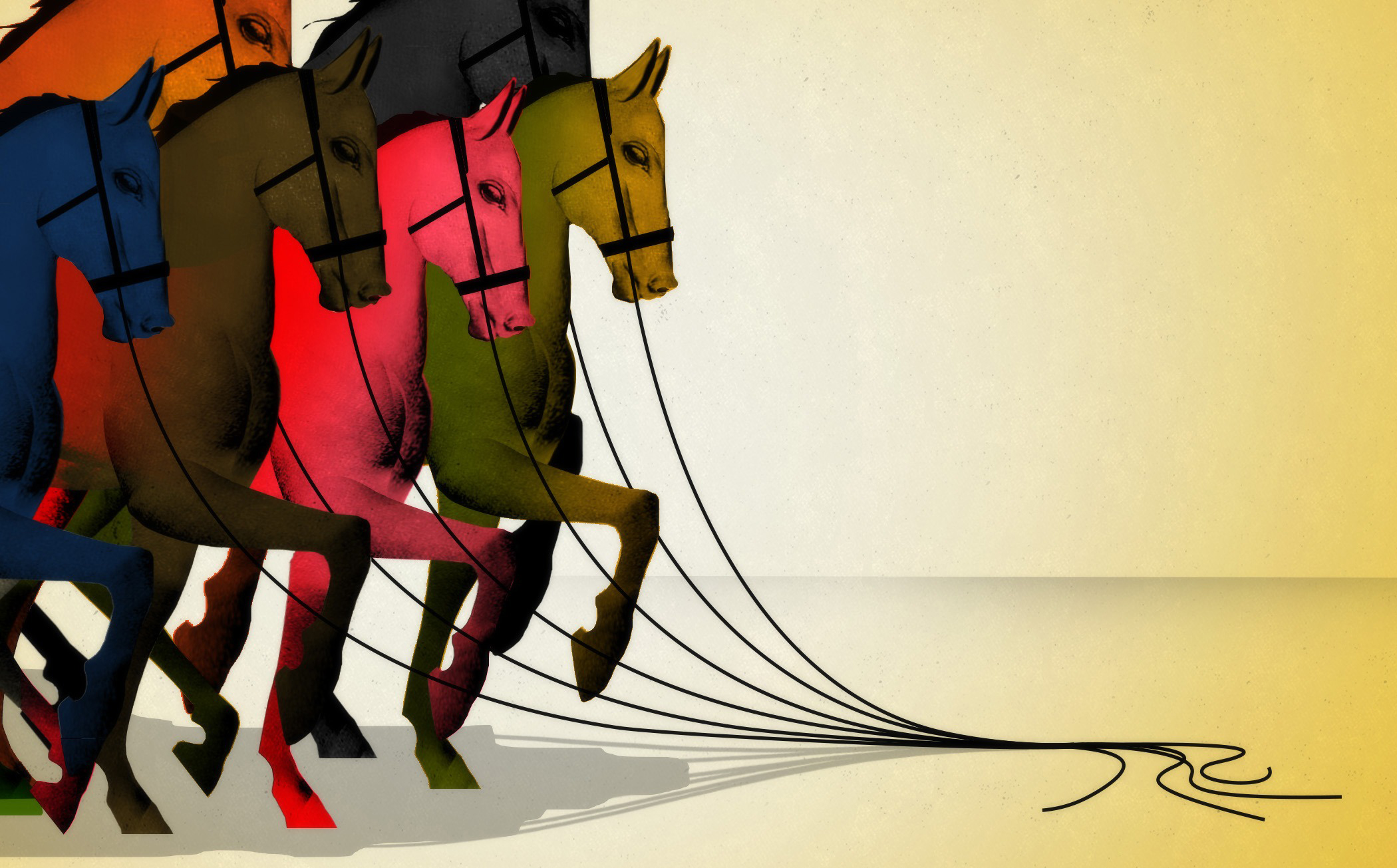

In a world of emergencies, leadership matters—and in 2016 it will become unavoidably obvious that the world lacks leadership. The days when heads of the G-7 industrial powers like the U.S. and Germany controlled geopolitics and the global economy are gone for good. The international group of today is the expanded G-20, which is much larger—including important emerging powers like China and India—yet agrees on much less. The result might be called a G-zero world, a global caucus whose members don’t share political and economic values or priorities. They don’t have a common vision for the future. Many years in the making, a G-zero world is now fully upon us.

For all the rhetoric from U.S. presidential candidates, Washington can no longer even pretend to play global police officer, because public support isn’t there for any action that might require long-term commitments of U.S. troops and taxpayer dollars. You may get a majority to say it’s time to send ground troops after ISIS, but Obama knows that support won’t last. The ugly response to the massacre in San Bernardino, Calif., suggests that U.S. public reaction to a major terrorist attack will not be as unified as it was after 9/11. And even if such an attack compelled the U.S. to act, it may have to act alone—there are now too many important international players with the political and economic self-confidence to simply ignore Washington’s lead.

That’s true even of allies. Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, former German Defense Minister, warns of an erosion in transatlantic trust, exacerbated by the U.S. presidential-election season. The campaign anthem will be “forget Europe,” he says—and it won’t come only from Donald Trump.

This doesn’t mean the U.S. is in decline. The economy continues recovering, while the American capacity for innovation is as healthy as ever. At a moment when even staid Europe faces serious security risks, the western hemisphere remains the most peaceful and stable region in the world.

Yet abroad, America’s once predominant influence is fading fast. In the Middle East, the most powerful terrorist organization in history occupies large sections of Iraq and Syria. Russia has paralyzed Ukraine and is bombing unchecked in Syria. China is challenging U.S. military power in East Asia and Washington’s institutional power everywhere else. Obama now relies on sanctions, drones and cybercapabilities to advance U.S. interests—blunt tools that do little to build the consensus needed to solve the world’s most complex problems. Few U.S. officials, even the most hawkish, are able to make a clear case for the role they think the U.S. can and should play in a new world.

Europe can’t help—its leaders are too busy coping with migrants, maneuvering around populist political rivals, working to keep the U.K. in the E.U. and helping Greece find long-term financial footing. China won’t fill the G-zero vacuum—it’s more active on the international stage, but only in pursuit of narrow national interests. Beijing is fully occupied with an anticorruption drive of historic ambition, a bid to revitalize Communist Party rule and a high-stakes economic reform process.

Who will take the lead in destroying ISIS, stabilizing the Middle East, containing the flow of dangerous weapons, mitigating climate change and managing international risks to public health? No one. The world’s many wildfires will burn hotter in 2016, because no one believes he can afford the costs and risks that come with putting them out.

The Middle East: Ground zero for G-zero

Nowhere is the G-zero problem more pressing than in the Middle East, where the only thing worse than the region’s authoritarian leaders are the chaotic states that lack leadership altogether. In Iran, conservative hard-liners, fearful that the lifting of sanctions will open the country to Western influence and awaken the appetite of the nation’s young people for change, will assert themselves. In Saudi Arabia, anxieties over Shiʻite Iran’s rise, growing U.S. indifference, royal-family rivalries and depressed oil prices will drive overreaction to the country’s many perceived threats and intensification of Saudi support for proxy wars on multiple fronts across the Middle East.

Bloodshed in Yemen—the worst crisis the world isn’t talking about—will continue. In Iraq, the Shiʻite-dominated government will export more oil but do nothing to persuade the country’s minority Sunnis to turn on ISIS, an essential step for reclaiming the Sunni-dominated land ISIS controls. The U.S., Russia, Turkey, France and others will continue to bomb Syria, and it will continue to have little military effect. Huge numbers of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan will sorely test stability in both countries—witness the thousands of miserable asylum seekers trapped on Jordan’s northeastern border.

ISIS will extend its international reach—though not its territory in Syria and Iraq, which likely has peaked—thanks to more than $1 billion in financial reserves, its mastery of social media and encrypted messaging, and its ability to attract a steady supply of new followers around the world. The terrorist group accomplishes this not simply by staging or even just encouraging spectacularly violent attacks abroad but by convincing others that it can build an Islamic empire with borders drawn by Muslim supermen, not Western politicians.

There is reason to fear we will see many more terrorist attacks in 2016, because the entrance of Turkey into Syria’s conflict will make it that much more difficult for young recruits to join ISIS in Syria—inviting them instead to carry out attacks where they live. In the Middle East, as nowhere else, fights are intensifying and no leader is willing to accept the full price that comes with leading the massive efforts required to restore something like order.

Europe: A weakened West

Five years ago, Europe’s leaders faced a single dominant threat in the euro crisis. Thanks to the resilience of Europeans, Germany’s determination to keep things on track and the pledge from Europe’s central banker to stabilize the euro zone by any means necessary, that crisis was resolved.

But in 2016, Europe will face a much wider variety of problems—without the unifying sense of crisis needed to forge collective action. Greece’s financial troubles will enter a new phase this year as its leftist, Syriza-led government struggles to navigate creditor demands, opposition attacks and frustrated voters. Spain’s government must negotiate away secessionist threats from Catalans. A skeptical Britain will vote on its European future.

By themselves, each of these risks is manageable. Add a million more migrants—and a public worried about the terrorism risks they may bring—and Europe’s political ground will shift further toward the populist right. At particular risk are hopes for maintaining Europe’s open borders. Many European governments have imposed new border controls, albeit on a temporary basis. Further terrorist attacks could expand this trend.

At the center of Europe’s attempts to manage these challenges is Angela Merkel. The indispensable regional leadership she has provided makes Merkel an exception to the regional chaos. But despite her popularity and the lack of a real alternative to her within Germany, Merkel is vulnerable to those who see refugees as future jihadis. G-zero threatens even this extraordinary leader through the potential breakdown of open Europe. “The euphemism of the coming year will be cooperation,” warns Guttenberg, who was Defense Minister under Merkel. Europe will see a “manifestation of a culture of the least common denominator.”

There is growing division between U.S. and European leaders. Transatlantic ties depend on common values. While those ties are durable, values tend to matter less during emergencies—which leaves countries looking out for themselves. “It is in Britain’s interests for there to be a healthy relationship between the U.S. and the E.U.,” says William Hague, the former U.K. Foreign Secretary. But Britain is prepared to make its own way in a G-zero world. “A declining Europe-U.S. relationship would be undesirable but not disastrous for the U.K.”

One piece of good news: Putin will probably prove less confrontational in 2016. He has effectively won the stalemate in Europe, and he believes he can parlay his power play in Syria into an end to sanctions. But a contracting economy, rising inflation and lower oil prices will further darken the mood of Russia’s people in 2016—and that could send Putin in search of foreign scapegoats.

China: Growing strong but refusing to lead

The best news for international security is that East Asia will remain relatively quiet in 2016. Political leaders in China, Japan and India are preoccupied with all-important domestic economic-reform plans and can’t afford conflicts that are bad for business. Compared with Europe and the Middle East, East Asia should remain calm—unless North Korea surprises us.

China will find other ways to challenge the dominance of the U.S. Beijing will use its $3.4 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves to finance ambitious alternatives to Western-led institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. China will become a new lender of first resort for governments of developing countries that don’t want to meet U.S. demands. U.S. allies like Britain and Germany, eager to diversify their economic partnerships and profit from China’s rise, will continue to follow China’s lead, extending the prolonged battle over whether global commercial standards are decided in Beijing or Washington.

But a stronger China still has no interest in filling the vacuum created by the G-zero order. Beijing won’t fight ISIS or help rebuild Syria. It won’t help ease tensions between Russia and the West. China is the world’s only government with a truly global foreign policy strategy. But that strategy involves solving China’s problems—not the world’s.

Still, it’s a strategy that speaks to some leaders’ interests. “A strong China offers economic opportunities for the U.K.,” says Hague.

There will be plenty of good news in 2016. Crucial, long-awaited reforms will continue to advance in India and Mexico, two of the world’s most important emerging markets. A strong group of leaders in East Asia will keep rivalries in check. Policy corrections in Brazil and Argentina will begin to pay dividends, even if the process of getting there is ugly. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia will profit from competition among the U.S., China, Europe and Japan for much-needed infrastructure investment.

But none of these good-news stories will help resolve the G-zero dilemma. Only a global emergency on a scale greater than anything we’ve yet seen can accomplish that—the sort of crisis that forces a new level of global cooperation based on the world’s true balance of power. It might be a war, a financial crisis, a public-health threat, catastrophic terrorism, an environmental disaster. Though that crisis is approaching, we’re unlikely to get there in 2016. When it finally comes, it will be the biggest story of our time.

This appears in the December 28, 2015 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com