Christmas in America had been anxious and somber during the four years of World War II. The peril and sacrifice of war was hard to reconcile with memories of the joyfulness of pre-War holidays, and by 1944 many American servicemen and women shared one particular Christmas wish: to be “Home Alive by ’45.”

That year, as war drew to a close in both Europe and the Pacific, it seemed possible that the wish might come true. But the war’s end hardly meant that the 2,000,000 men and women eligible for separation—those who could be done with active duty—were home in their civvies by the time the holiday rolled around. With all resources dedicated to winning the war, neither the Army nor the Navy had spent much time thinking through the logistics of bringing everyone home until after the fighting was finished. And so it was without too much preparation that Operation Magic Carpet began in September 1945 to bring the troops back home to the United States.

As Christmas approached, the Army and Navy launched Operation Santa Claus to expedite Operation Magic Carpet, with the goal of rushing as many eligible men and women home for the holiday as possible. But violent storms at sea and the volume of eligible servicemen conspired to thwart the high ambitions of these operations. And so throngs of American military personnel—some 250,000 in all, some with brand new discharge papers and some just a day or two away from separation—found themselves back on American soil for Christmas 1945, but not quite home. Instead, they faced the worst air, rail and automobile traffic jams in history. The rule of thumb in the days immediately preceding Christmas 1945 was that a westbound train would be about 6 hours late, and an eastbound train about 12 hours.

The predicament was met with overwhelming understanding and good nature among the servicemen. Upon being asked by a newspaper reporter what he thought about being among the 150,000 who were stranded along the West Coast for Christmas, an Army Private trying to get home to Texas responded that simply stepping on U.S. soil was, “the best Christmas present a man could have.”

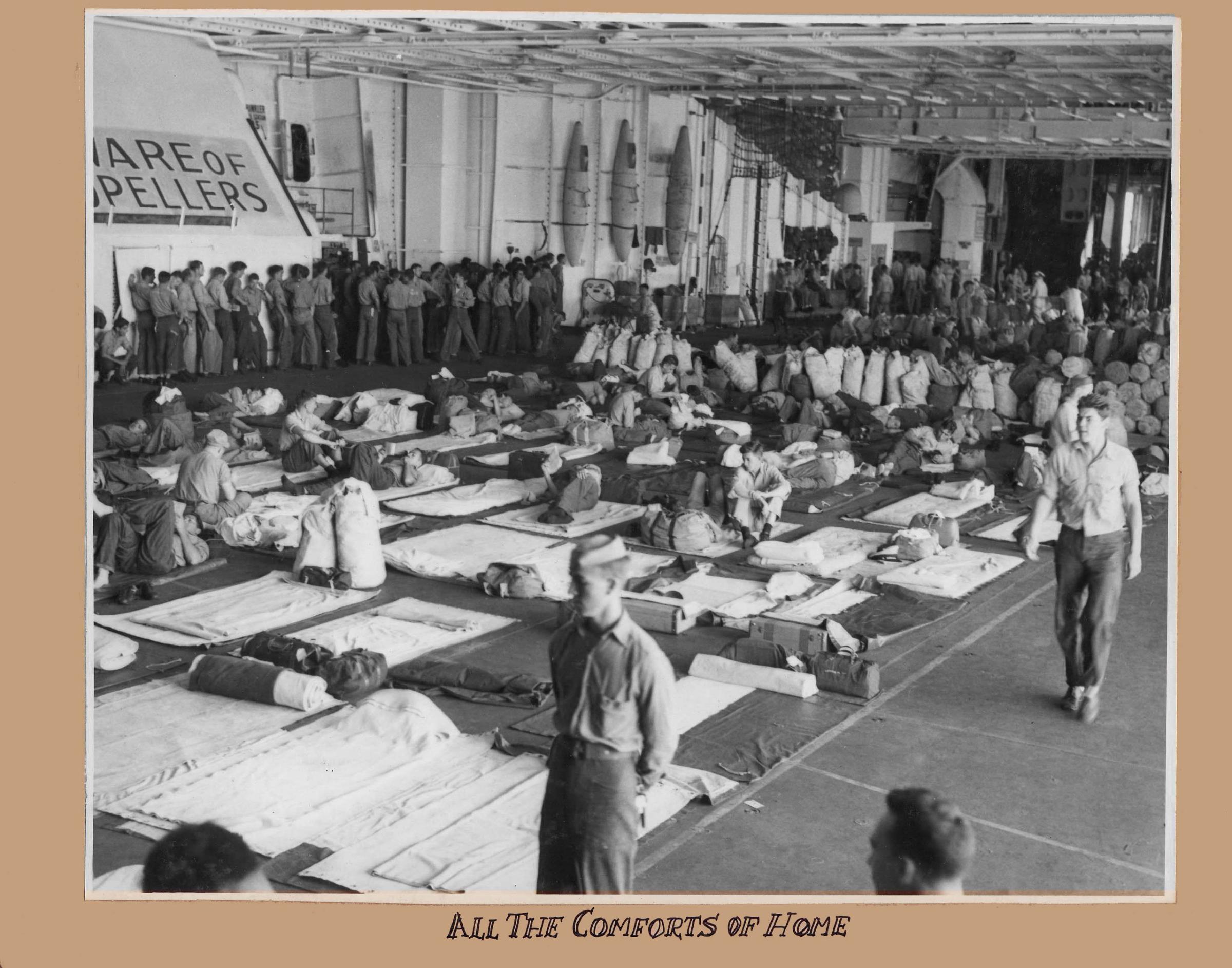

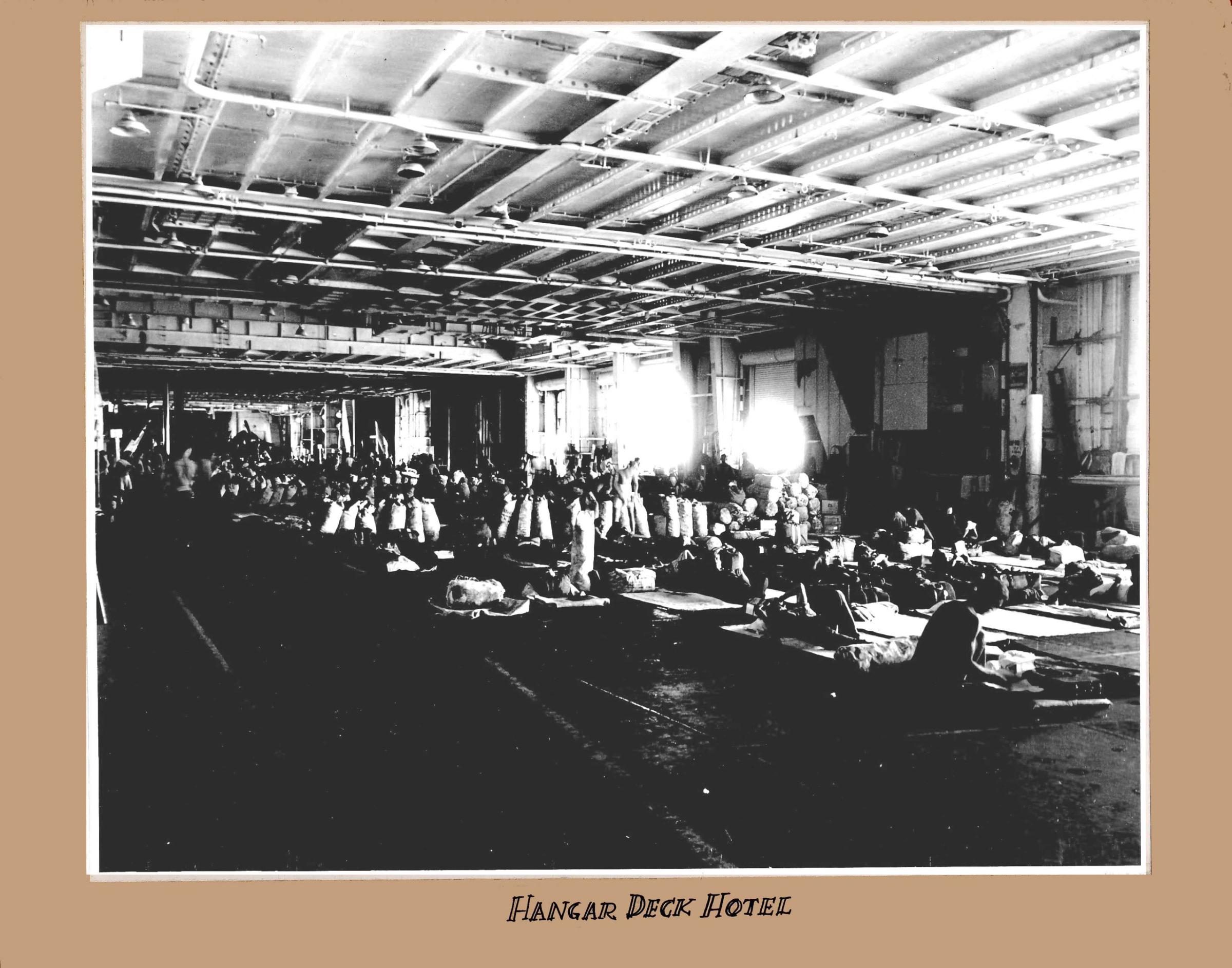

Civilians near the West Coast “separation centers,” where soldiers and sailors were being relieved from active duty, enthusiastically opened their homes to the new and soon-to-be veterans, while many of the 50,000 men and women awaiting discharge from points along the Eastern Seaboard were required to have Christmas dinner at the separation center itself, or sometimes even on the ships which had just brought them there. But even then hardly a complaint was heard, as the troops enjoyed hearty meals provided by the Army and Navy while noting that this year ration tins were nowhere to be found.

As reported in the New York Times: “tens of thousands of tired troops, dreaming of a white Christmas, are seeing enough of it from (train) car windows to last them a lifetime.” A full 94% of the passengers on trains originating from the West Coast on Dec. 24, 1945, were military or recently discharged military personnel. Even recently minted veterans unfortunate enough to still be in route between their separation center and home on Christmas were cheerful about their holiday circumstances. Christmas dinner with their families would be eaten on whatever day they arrived home, it hardly mattered whether it was December 25 or a few days later.

Goodwill was everywhere. Civilians gifted their train tickets to returning servicemen and women. Others threw spirited, though condensed, parties for the trainloads of veterans who had even just short stopovers at their town’s station. In at least one instance, a trainload of vets returned the favor by spending their 20-minute layover in Salt Lake City taking up a collection of $125 ($1,650 in 2015 dollars) for a local charitable cause they learned about at the newsstand during the stop.

Citizens even volunteered to sacrifice Christmas with their own families to get veterans home before the New Year. A Colorado trucker drove 35 veterans marooned in Denver to their homes in Dallas and 34 points in between. The driver refused to accept payment, insisting the men spend the money on presents for their families. A Los Angeles taxi driver drove a carload of six new veterans 2,700 miles home to Chicago. Another drove six veterans from L.A. to their homes in Manhattan, The Bronx, Pittsburgh, Long Island, Buffalo and New Hampshire in exchange for nothing but the cost of gas.

“This is the Christmas that a war-weary world has prayed for…” proclaimed President Truman at the National Tree lighting ceremony on Dec. 24, 1945 – and Americans did everything they could to give their servicemen and women the holiday they deserved.

Matthew Litt is the author of Christmas 1945 – The Greatest Celebration in American History and the founder of the Bashful Buffalo American History Co. He was an adjunct legal writing professor at Seton Hall Law School and a practicing attorney before leaving the law to follow his bliss—American history.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com