Go to any yoga studio these days and you’re liable to find a wide variety of options to fit your yoga needs. But when the practice first crossed into the Western mainstream in the early 1970s, Iyengar yoga was the name that many new practitioners encountered first.

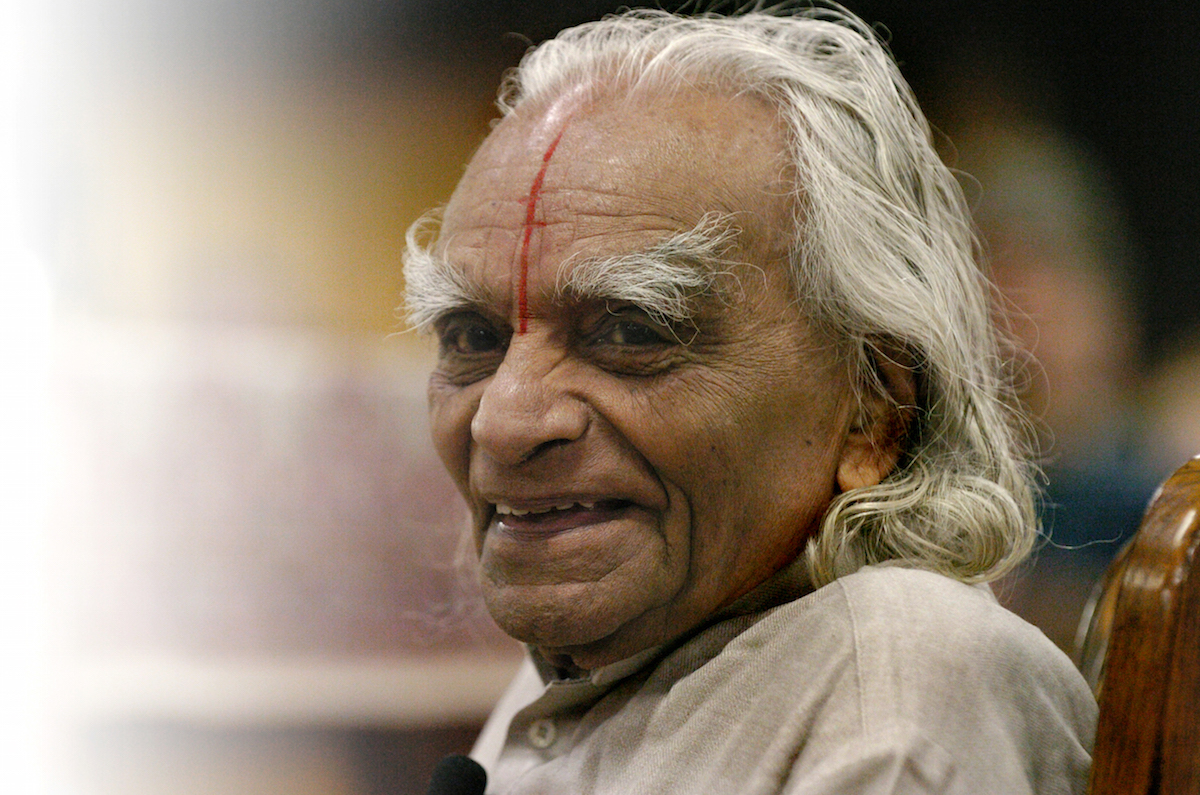

B.K.S. Iyengar, after whom the practice was named, was born on Dec. 14, 1918—he would have turned 97 on Monday—and died last year. He was not the first to tell the wider world that yoga existed, but he was instrumental in helping yoga become something that anyone could do. In the early 20th century, yoga was often described in the Western press as a religious and spiritual practice, and an object of curiosity.

For example, though TIME in 1937 described an early Yale study of the physical benefits of “an ingrown Hindu philosophical system whose object is fusing the ‘individual soul’ with the ‘universal soul,'” a more common yoga story of that era was the 1936 tale of “a set of photographs taken in broad daylight by two hard-headed Britishers…[of] a white-robed Indian Yogi reclining several feet above the ground in a sculpturesque attitude of repose.”

In 1947, despite the fact that many celebrities (Aldous Huxley, for example) had become fans of yoga, TIME noted that it was “still as mystifying as Sanskrit to the average American.” Those who did practice yoga outside of its homeland tended to be more interested in its spiritual benefits than its physical ones; even the Beatles, who helped make the name of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi world famous in the late 1960s, were open to changing their philosophies and not just their bodies.

That was right around the time that Iyengar released his 1966 book Light on Yoga. It was an era of great openness to the concepts yoga practitioners had long espoused, and a good time to capture an audience among those who were seeking a new way of looking at the world. We know today, however, that yoga reaches far beyond that philosophical niche. So what happened?

When Iyengar was included on the TIME 100 list of the world’s most influential people in 2004, the actor Michael Richards described how its philosophy set it apart. It wasn’t a matter of the poses themselves, or his celebrity students. The real thing that made Iyengar special, Richards wrote, was that his focus on the physicality of yoga—rather than the grander concepts behind the practice—allowed people with a wide range of beliefs to experiment with yoga. And that, he wrote, made Iyengar yoga particularly capable of crossing global boundaries:

Iyengar teaches practitioners to lavish attention on the body. The goal is to tie the mind to the breath and the body, not to an idea. His philosophy is Eastern, but his vision is universalist. You can incorporate Iyengar into your life and yoga practice—but ultimately we’re Westerners on Western soil.

In my acting, as in my yoga, every nuance, every detail and gesture is the subject of my focus. I’m always paying careful attention, like a pianist, and translate that attention into my performance. Iyengar knows what the body needs, and he’s introduced to the West the Easterner’s best path to health and well-being.

Read more about B.K.S. Iyengar, here in the TIME Vault: Bringing the East to the West

Read a 2001 cover story about the science of yoga, here in the TIME Vault: Yoga as Therapy

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com