Correction appended, Jan. 4

Each year, as TIME LightBox commemorates the photographers we lost over the last 12 months, we pay tribute not only to their contribution to shaping the past, present and future of photography but also, as this year’s list shows, to their unwavering devotion to emerging image makers.

Some were pioneers in their field, while others were legends in the making whose deaths came too suddenly. Whether they led workshops, nurtured singularly, or initiated a new school of thought, their absence was deeply felt by those they championed. All offered guidance, wisdom, accessibility and support to those still finding their own visual fingerprint. “It is something when you have a champion and a mentor and they’re gone,” says Aperture’s Denise Wolff.

The photographers we lost this year leave behind a legacy that far outlives them. Even in death, their mentorship immortalizes their contribution to the archives of visual history.

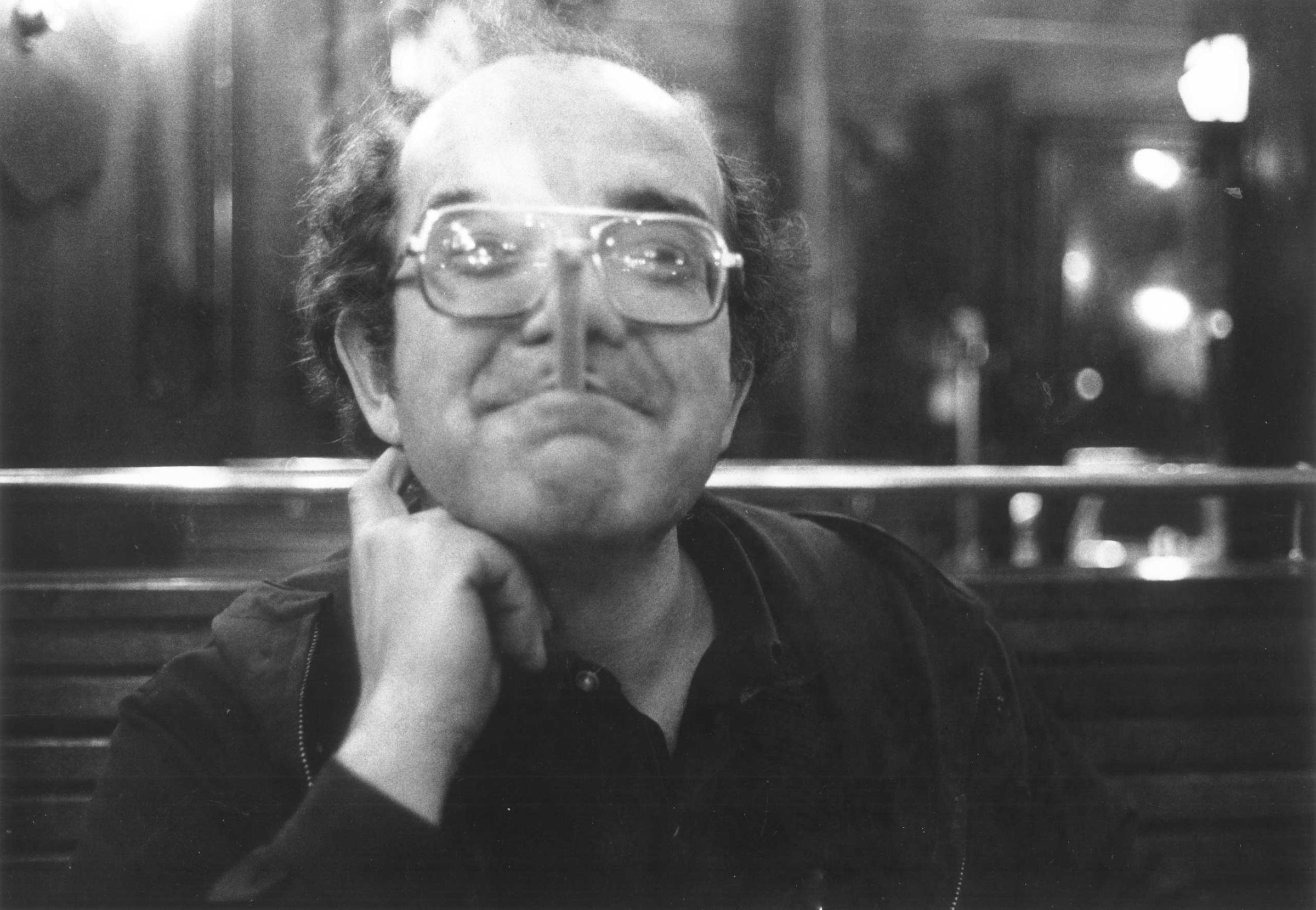

Charles Harbutt (1935-2015)

In the late 1960s and 70s, a slough of photographers joined Magnum Photos, including Mary Ellen Mark, Abby Heyman, Jeff Jacobson, Alex Webb and Jean Richards. All were championed by Charles Harbutt. A couple of times a president of Magnum, he was arguably one of the most influential American photographers of his time. “He was the person a whole generation of photographers looked to,” says Jeff Jacobson, who worked with Harbutt at Magnum. “For those straddling that line between art and photojournalism, who were involved in documentary photography but not in a strict narrative storytelling sense, Charlie was it.”

In 1981, Harbutt left Magnum to form Archive Pictures with his wife, Joan Liftin, as well as Mary Ellen Mark, Abigail Heyman, Mark Godfrey and later, Jacobson. Having become disillusioned by traditional photography, he left the narrative, classical form behind and forged a new photographic language. His work became mysterious and metaphorical. “Maybe I had a sell-by time, an expiration date for being a witness,” Harbutt writes in the afterword of his 1974 book, Travelog. “I started questioning this reportage for myself. A host of manipulators had so corrupted and warped public events, I could no longer trust the authenticity of what I was seeing. Gradually my pictures became more about what I experienced in my day-to-day wanderings.” Harbutt died at the age of 79 on June 29. He had emphysema.

Cotton Coulson (1952-2015)

Legendary photographer and filmmaker Cotton Coulson died May 27 losing consciousness while diving off of the coast of Norway. He was 60. Coulson shot more than 40 stories for National Geographic and National Geographic Traveler, shooting across Europe, from the Arctic and Scandinavia to Italy and France. He immersed himself completely into the different stories that he was sent to do and was wholly dedicated to whatever the situation needed. “If he was in Scotland he’d come back with a kilt. If he was in Rome he’d come back with an all-leather, Italian race car driving outfit,” says Maura Mulvihill, a National Geographic Society Senior Vice President. “While shooting incognito at a nude beach, he even agreed to go naked, except for his photography vest.”

But when it came to photography, he was very serious, even critical. He had grown up in New York, where early on he became fascinated with the arts. His mother introduced him to paintings and he went on to study art in high-school and then later at the New York University Film School. Coulson served as associate director of photography at U.S. News & World Report, where TIME International Photo Editor Alice Gabriner was a young photo editor. “Cotton brought to the magazine a burst of creative energy and out-of-the-box thinking,” she says. “He had natural confidence in his own way of seeing, and directed the magazine’s coverage of major stories, including the Tiananmen uprising in 1989, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the first Gulf War. His artful sensibility was unique in the realm of news photography. He appreciated subtlety and the unexpected.”

Coulson went on to become director of photography at the Baltimore Sun and vice president of CNET Networks, in addition to the National Geographic. He worked as a duo with his wife and photography partner, creating their own studio called Keenpress. They were an unusual, talented, loving couple, who grew into each other with a sort of romantic sense of place. “We are very much like Siamese twins, with one another day and night, 24/7. Very seldom we were away from each other these last ten years,” his wife, Sisse Brimberg, tells TIME. “We would try to push harder and try to do something more, and survive the other person.”

“Over the course of a career, mentors are crucial, and often you don’t realize the influence of one person until many years later,” says Gabriner. “I’ve worked with so many photo editors over the years, but Cotton’s impact stands out – not only as a personal mentor, an independent thinker who followed his instincts and forged his own path, but also for the sophisticated visual legacy that he has left the larger photo world.”

Hilla Becher (1931-2015)

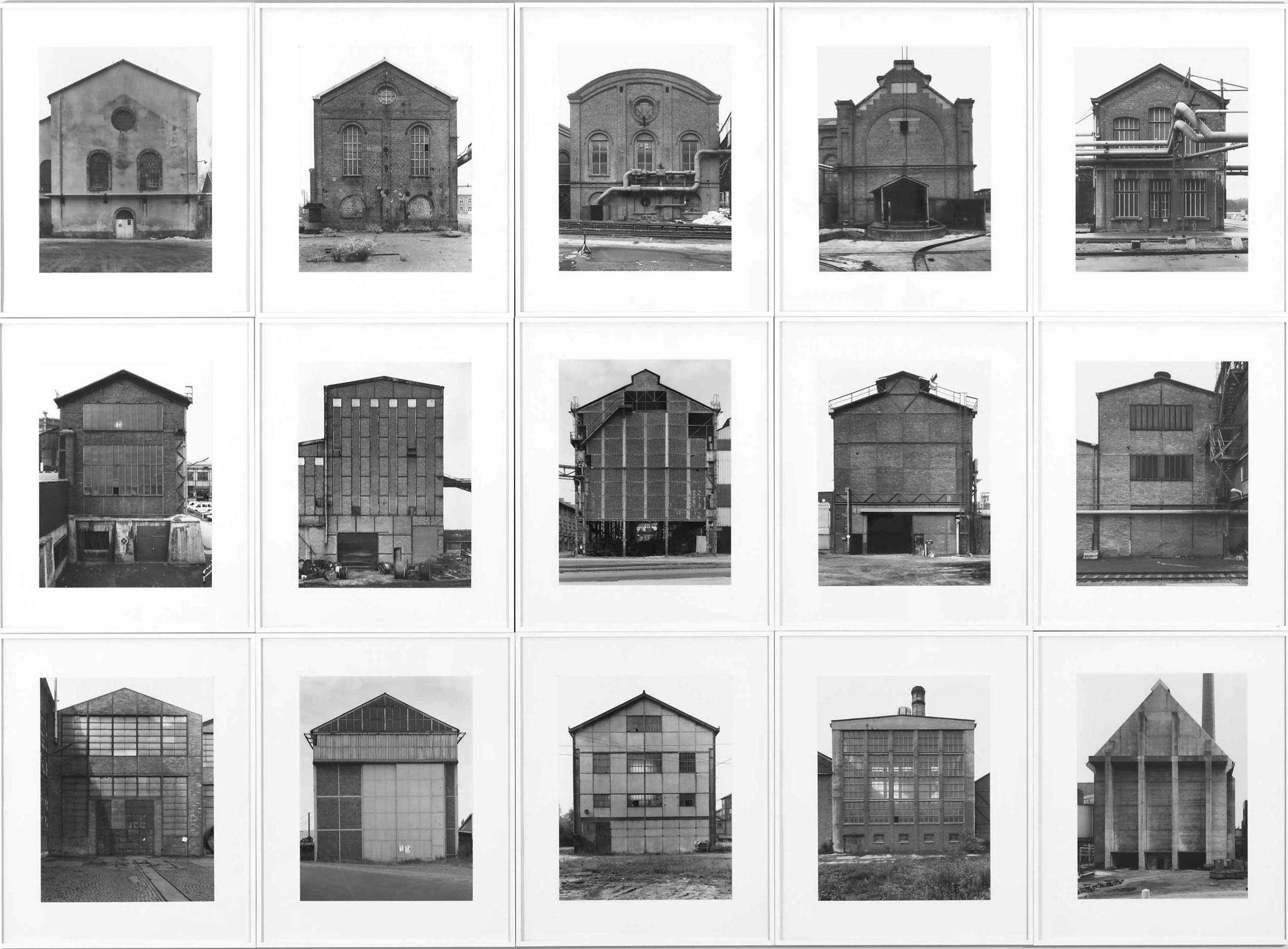

Hilla Becher, part of another famed photographic duo, died on Oct. 10 at 81 years of age. Known for their typologic series on industrial structures that typified the western landscape, the German photographer and her husband Bernd were a prolific force in the photography world. “Hilla Becher was a remarkably incorruptible person,” Thomas Struth told TIME earlier this year. “I loved her uncompromising but open-minded and gentle attitude, always curious, not sentimental but loving.”

Becher first met Bernd while attending the same art school in 1957. Two years later, they began photographing together. Over 50 years, the duo captured water towers, silos, coal bunkers, blast furnaces and gas tanks. Their book, a scarce and early major monograph called Anonyme Skupturen, was released in the early 1970s, displaying in black-and-white in grids of these structures. The ideology behind their characteristic spreads, often called the Becher School, influenced artists such as Thomas Ruff, Struth and Andreas Gursky.

Mary Ellen Mark (1940-2015)

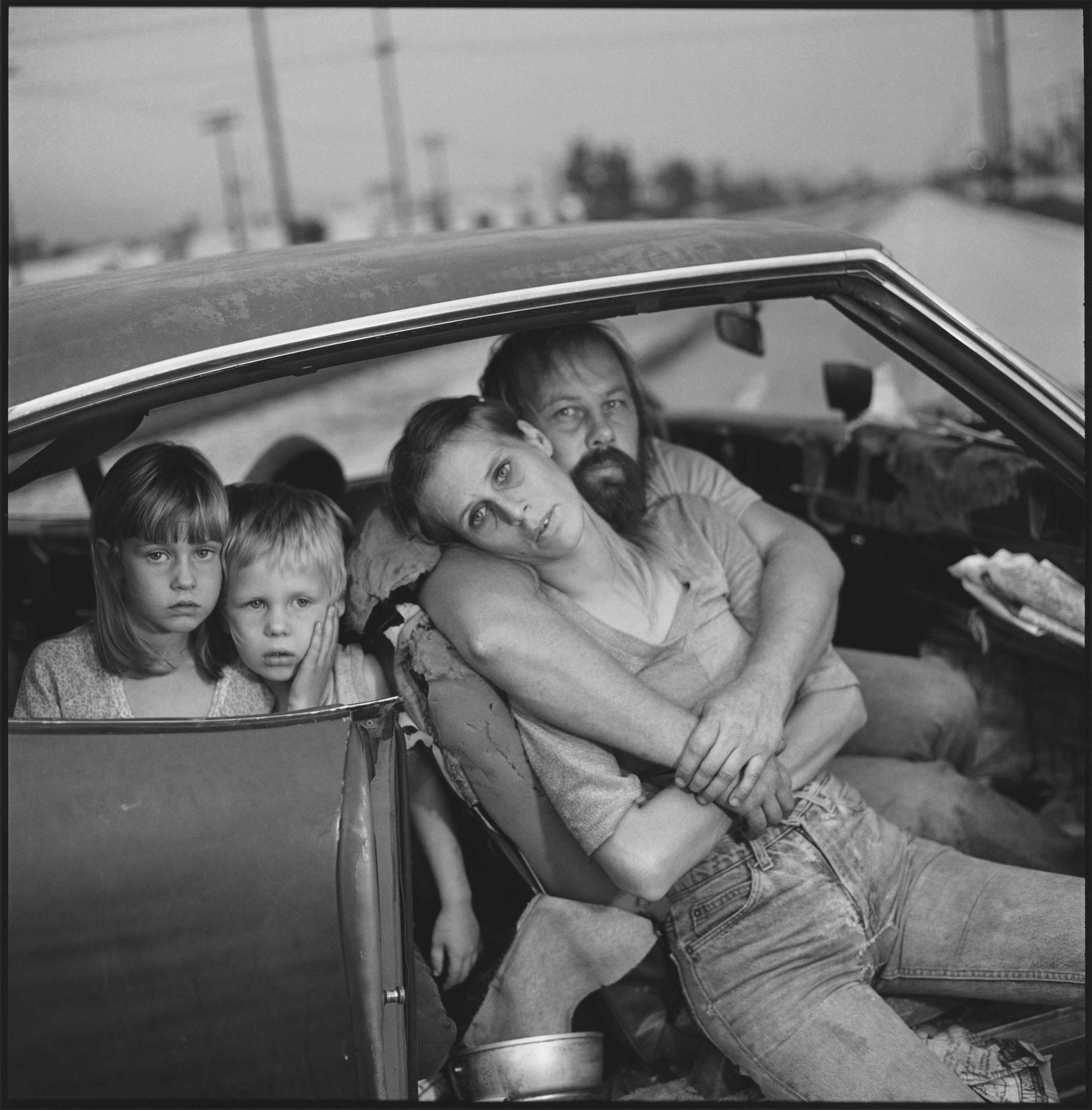

In over 50 years as a celebrated humanist photographer, Mary Ellen Mark became one of the greatest photojournalists of her time: she produced 22 books and her work appeared in the pages of magazines such as LIFE, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, the New York Times Magazine and Vanity Fair. Mark was also one of the few female photographers at Magnum Photos when she joined in 1977. Her images reveal a stunning intimacy with the people in her photographs, whether it was a celebrity or a great artist or a prostitute or low-income circus performer. She remained in touch with many of her subjects right up until she died. Her final project was focused on Tiny, a young prostitute from Seattle whom she had photographed for LIFE in the 1980s in her book, Streetwise. “She collected people like that,” says Denise Wolff, who worked with her on her last Aperture book. “She was fierce when she supported someone. There was never any doubt where you stood with her.”

Mark was not always easy to work with, Wolff says. “She had a powerful intensity, almost like a restless presence. You could feel the ground move when she walked in and she knew what she wanted, whether it was rational or not.” But as tough as she was, she was just as generous. She taught a workshop, pushing and challenging her students beyond what they were comfortable with. In her last weeks, she worked tirelessly to publish what she wanted to pass on to young photographers in her final Aperture book.

“I was thinking about how fleeting and how precious life is and the choices that you make in life, the luck of being born in the right bed, to parents who support and help you, and who love you,” said Mark in the afterword to Tiny: Streetwise Revisited. “That doesn’t always happen—and then, what happens when that doesn’t happen?” She died on May 25 at age 75.

Saleh Mahmoud Laila (1988-2015)

Anadolu Agency journalist Saleh Mahmoud Laila was killed in a suicide car bomb attack near Aleppo, Syria on Oct. 8. Laila, 27, had returned to Aleppo to cover the conflict last July after having recovered from burns from an airstrike in Turkey. Laila’s photographs document the civil war in Syria, which is considered one of the deadliest countries for journalists, with at least 84 reporters killed since the conflict began in 2011, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

He talked about his country and the Syrian tragedy with humor and hoped to be alive when Syria would became a peaceful land, says Ahmet Sel, the head of the Visual Director of the Turkish Anadolou Agency. Laila’s humor belied his stoic sense of gravitas. He lived and died for Syria. “He wasn’t a fighter and the idea of taking up arms wasn’t an option for him because of his personality,” says freelance journalist Emma Beals. “But he was committed to the revolution. For him, it was a matter of what he wanted for his people and for himself and for his country by telling those stories and informing people about what was happening.”

Khaled al-Hariri (1961-2015)

Syrian photographer Khaled al-Hariri photographed at Tishreen, a local Syrian newspaper, before joining Reuters in 1991 in Damascus. He would work at Reuters for more than 20 years. He mentored many young photographers in Syria. Hariri, died at age 54 following a long illness.

Sergiy Nikolayev (1972-2015)

Serhiy Nikolayev was killed Feb. 28 in crossfire in the village of Peski, northeast of the rebel-controlled city of Donetsk. Since 2014, at least six journalists and two media workers have been killed in Ukraine, according to CPJ research. That year, the organization documented frequent press freedom violations including abduction, attacks and the blocking of broadcasts.

Since 2008, Nikolayev had worked for the Kiev-based daily Segodnya, covering war in Iran, Somalia and Libya. In 2013, he put on an exhibition that documented the impact of war on children titled, A childhood not for children. “He would go with his camera into the fire so that he could show life as it happened,” Segodnya editor-in-chief Olga Guk told CPJ. “He did not spare himself. He was the bravest of professionals.”

Ruben Espinosa (1984-2015)

The execution-style murder of 31-year-old Mexican freelance photojournalist Rubén’s Espinosa on July 31, which exposed a failure to provide protection to journalists in one of the country’s most dangerous states, was met by an international outcry against government repression in Mexico. Since 2010, more than 80 reporters have been murdered in the country, according to advocacy group Article 19. Espinosa, however, was the first journalist-in-exile to be killed in the federal district.

Espinosa had been working in Veracruz for an investigative newsmagazine called Proceso, before moving to Mexico City after reportedly receiving death threats. He was known as a critic of Javier Duarte, the governor of Veracruz, and a champion of freedom of expression. He shared his knowledge with the next generation of photographers, teaching teens about framing, the decisive moment and photographic technique, but also ethics, solidarity and commitment to society. ”He knew that his camera was the best weapon to highlight the injustices,” says friend and colleague Félix Marquez. “He was a brave young man who gave his life reporting in a country where telling the truth can be a crime.”

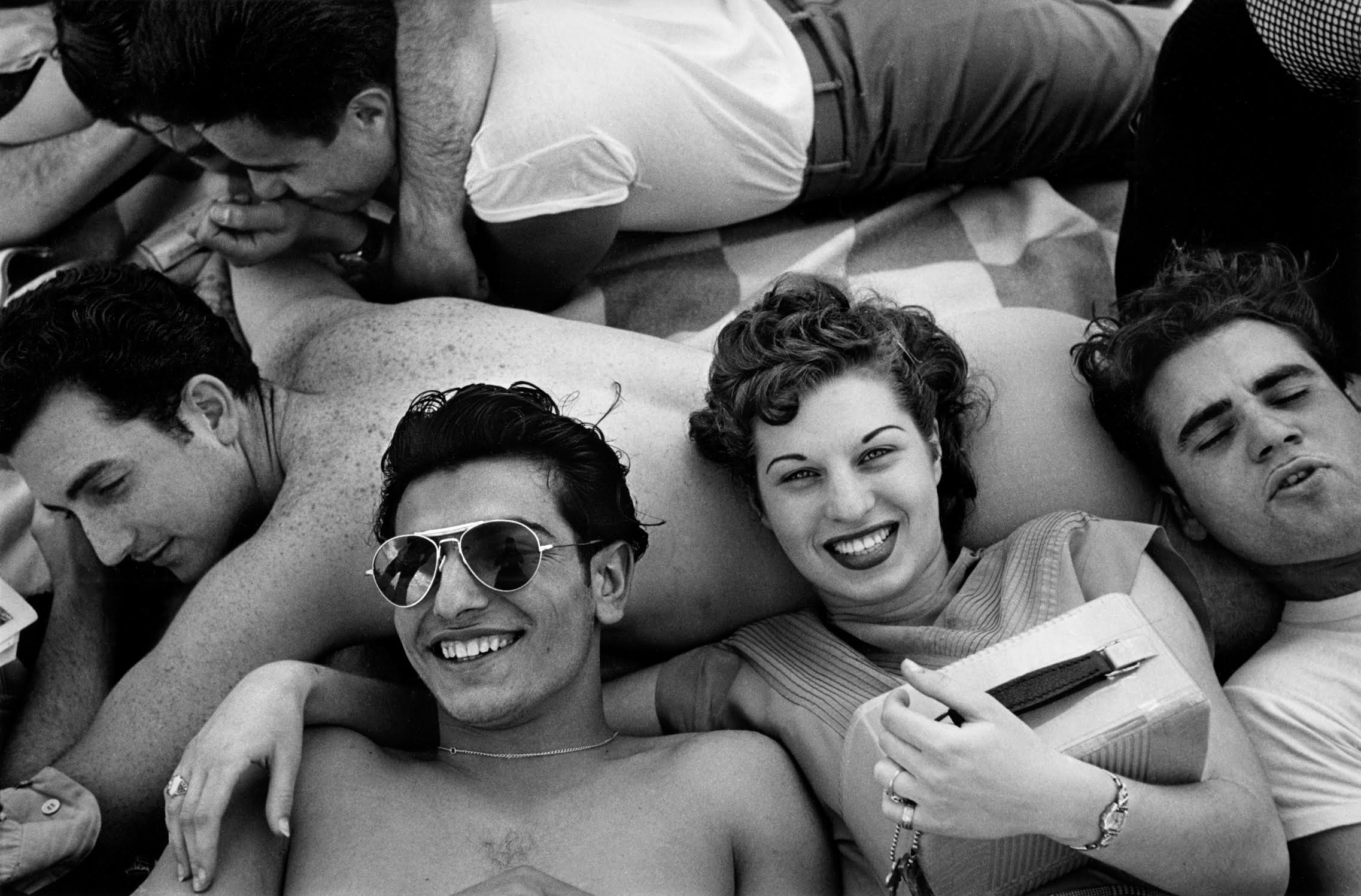

Harold Feinstein (1931-2015)

Harold Feinstein loved Coney Island. While many others have photographed the famed boardwalk and amusement park, no one did so with such an eye for its storied charm. “It was a lifelong obsession,” National Portrait Gallery Head of Photographs Phillip Prodger tells TIME. “He saw it as full of people like him—ordinary people, not materially privileged, but genuine and unspoiled, limitless in possibilities.”

Feinstein began his career in photography at the age of 15 in 1946 and within four years, his work had been purchased for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). He joined the Photo League, a cooperative of photographers in New York. He was one of the legendary “Jazz Loft,” and a prominent figure in the New York City street photography scene. He taught too. Former New York Times photocritic A.D. Coleman calls him “one of a small handful of master teachers whose legendary private workshops proved instrumental in shaping the vision of hundreds of aspiring photographers.”

Determined not to sell out or do anything remotely commercial, Feinstein had spurned all the usual sponsorships from Kodak and others camera makers. Feinstein died July 20 at 84.

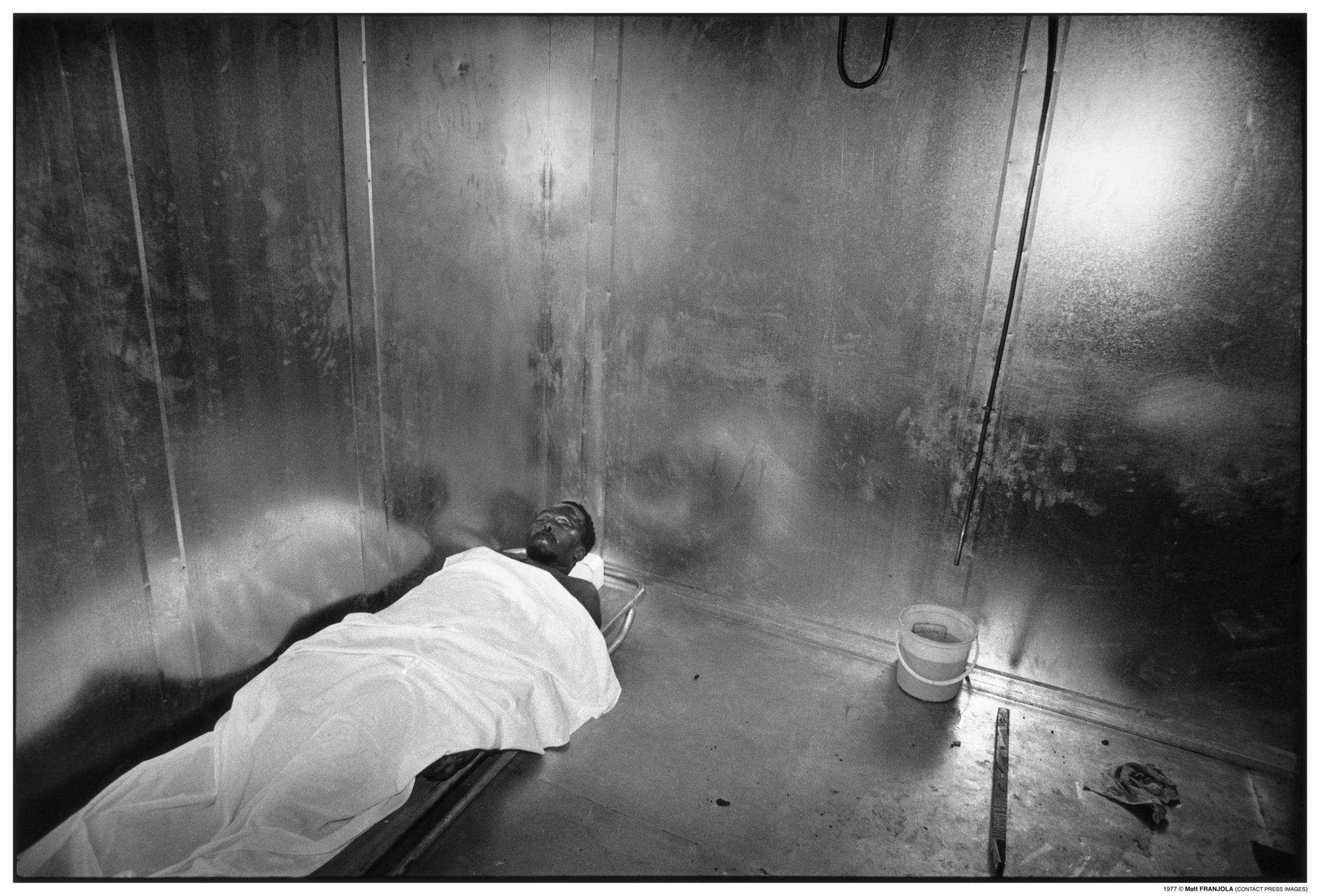

Matthew Franjola (1942-2015)

Reporter and photographer for the Associated Press, Matthew Franjola was among the last Americans in Saigon as it fell to the North Vietnamese in 1975. During his distinguished career, he reported in Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, South Africa and Rhodesia, where he worked on some of the most dangerous stories. “He lived a black-and-white existence in a colorful world,” former UPI colleague, David Hume Kennerly, tells TIME. “He was like Indiana Jones before that character was even conceived. He was a bigger than life character. When he came back to the States after so many years in Asia and Africa, his ex wife said it was like bringing King Kong out of the jungle.”

Franjola was born in the Bronx and studied at the state university in Cortland, N.Y. He trained for the Peace Corps in 1964 and went on to work for a war supplies company in South Vietnam, before becoming a stringer for the AP. Using a pseudonym to protect his identity, he captured the famous image of the body of Steve Bikko, an anti-apartheid activist in South Africa. Franjola died Jan. 1, he was 72.

Christopher Dadey (1974-2015)

London-based fashion photographer Christopher Dadey was known as one of the best catwalk photographers in the industry, boasting clients like Sibling, Bora Aksu and Vivienne Westwood. That he shot some of the greatest catwalk designers of our time in the UK and worked with many designers form just one pasrt of his reputation. He was also known as being a fair photographer, setting some of the most affordable rates in the industry so he could service designers that ranged from newly emerging to well-established.

His kindness in a gritty, competitive fashion world made him stand out, as did his deep cognizance of branding, coupled with a technical bravado. But the greatest testament to his talent were his images. “He nearly always got that perfect shot, with the girl at exactly the right position on the runway with her hands and feet well placed,” says FARBLACK Ltd. director Courtney Blackman. “There was a real harmonious synergy with all of his images.” Dadey died on Sept. 3. He was 50.

Marc Hispard (1938-2015)

French fashion photographer Marc Hispard passed away on April 25 in Belgium at 77. At 15, he began his career at the professional photographic lab Pictorial Service in Paris, while studying at Ecole du Louvre. Three years later, he worked for Le Jardin des Modes, a French women’s fashion magazine. He went on to collaborate with the magazine ELLE, as well as Italian Vogue, American Mademoiselle and Sports Illustrated. In 1986, he started ELLE USA with three other photographers.

“He was a real gentleman,” says Coolife Studios photographer Pauline Rochas. “He belonged to the masters. He had exquisite taste, a chic presence, and a kind of elegance about him that suggested that he was from another time. But also, he was a real authentic talent, photographically. He never shot digital and was a real purist.”

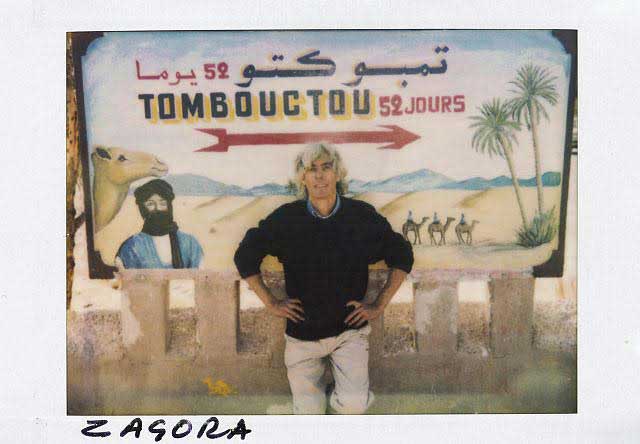

Jean-Luc Manaud (1948-2015)

French photographer Jean-Luc Manaud, known as the “lord of the desert,” died on Feb. 28. Born in southern Tunisia in 1948, Manaud returned to France at the age of 14 and trained in a school of architecture. He went on to photograph conflicts around the world, as well as the people and landscapes of the desert, from Niger to Chad to the Western Sahara. In 2000, Manaud published a few books and travel diaries that examined the dignity of various desert-dwelling nomadic people. “If you want to know Jean-Luc, look at this pictures,” says his friend François Guenet, a longtime friend of Manaud with whom he founded the Odyssey agency in 1989. “His photographs question. And he nearly sacrificed everything he had for them.”

Christopher Agou (1969-2015)

French documentary photographer and street photographer living in NYC, Christophe Agou died on Sept. 16 at 46. A member of the In-Public photography collective and winner of the 2010 European Publishers Award for Photography, Agou’s documentary-style images exhibit psychological depth. He captured the essence of the moment and approached every project with profound intuition, says his wife, Niloo. His In The Face of Silence series is a portrait of the lives of French family farmers in the Forez region in Paris. His Life Below essay provides a look at the underground world of the New York City subway, with close-up shots that accent emotions and moods. “Christophe took photos like someone devouring the most succulent dessert,” says his friend Julien Jourdes. “He bit until nothing is left, then smiled to release his pleasure. He was a genius at assembling pictures, objects, sculpture, words, food and friends.”

Dan Farrell (1930-2015)

Daily News photographer Dan Farrell has almost done it all. He’s been to every (baseball) World Series, he covered horse racing, as well as boxing matches. He golfed with Bob Hope and rode the subway with Bing Crosby. He got shots of Muhammad Ali, traveled with Pope John Paul II across Europe and accompanied Harry Belafonte on the USA for Africa tour. “The love of photography was his whole life,” his daughter, Kathy Farrell Natoli tells TIME. “Everywhere he went he had a camera around his neck. He was the official photographer at every party. Everybody came to him for advice about photography and he loved giving it.”

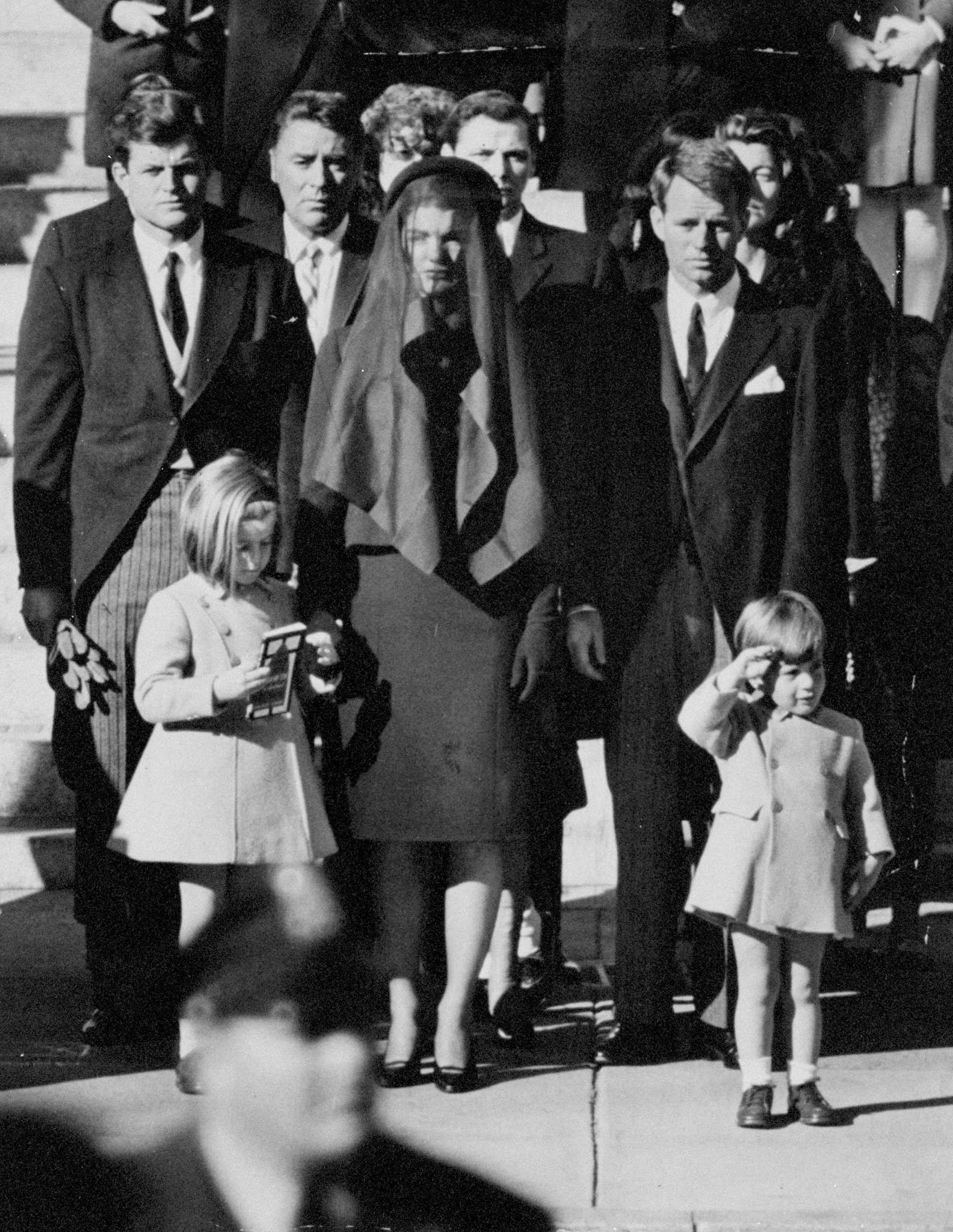

His iconic image of young John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting his father during his funeral was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize, but lost to Dallas Times Herald‘s photographer Bob Jackson, who captured the moment when Jack Ruby shot Kennedy’s assassin. “He said it was the saddest day of his life,” Natoli says. “He was across the street from the church and he had one chance to get the shot. He read Jackie Kennedy’s lips as she bent down to little John with the veil over her face. ‘John, salute,’ she said. He didn’t do it right away and so she said it one more time and my dad snapped the picture.” Farrell died on April 13 at 84.

Hal Gould (1920-2015)

Hal Gould died on June 25. He was 95. Born in Wyoming, he grew up on a ranch in New Mexico. Gould was a longtime photographer and curator of the fine art photography scene in Denver. After serving in the army during World War II, he studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago. “I gave up painting and changed to photography because I thought it was the most dynamic medium for artistic expression of the 20th century,” Gould told CPR News in 2009. “And people laughed at me then back in 1949 when I said that, but now they’re beginning to believe it.”

His images embodied the American West, as well as beyond, including China, Africa and Antarctica. In 1963, Gould co-founded the Colorado Photographic Arts Center in Denver, before opening the Camera Obscura Gallery in the Golden Triangle neighborhood. “He lived the hell out of it-and on his own terms,” wrote Shannon Piserchio, a documentary maker, on his Facebook wall. “The honesty and candor in which he recounted his rich and storied life, both in and out of photography, and the experiences we shared together have moved me in deep and profound ways.”

Elwin Musser (1919-2015)

Known to many as “Flash,” Elwin Musser lived and breathed photography. He took the renowned photograph of the plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens and their pilot on Feb. 3, 1959. The photograph was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and was later named one of the 100 Photos of the Century by the Associated Press. Musser worked as a news photographer for the Mason City Globe Gazette for 35 years. He was a member and past president of the Iowa Press Photographers Association. He died March 28 from complications from cardiac arrest. He was 95.

Kikujiro Fukushima (1921-2015)

Renowned anti-war Japanese photographer Kikujiro Fukushima started documenting survivors of the atomic bombs dropped on his country when he photographed Sugimatsu Nakamura, a 43-year-old fisherman and survivor who suffered from the bomb’s effects. His work criticized Japan’s decision to go to war in World War II, and the government’s refusal to compensate the victims. “He lived through the tumultuous years after the war and infiltrated the Self-Defense Forces and weapons industry with his stories while fearlessly challenging taboos,” says Saburo Hasegawa, the director of Japan Lies—The Photojournalism of Kikujiro Fukushima, a documentary on Fukushima. “[He] was a legend to us.”

Fukushima was stationed in Hiroshima in the Japanese military, where many of his comrades were killed. He told Japan’s Self-Defense Forces head of public affairs that he would give them free photographs if they gave him access. But he had devised another plan. “If the government or corporations knowingly deceived the public by breaking the law, it’s O.K. for photographers to break the law in order to uncover the truth they are hiding,” Fukushima explained in Japan Lies. In 1982, Fukushima moved to an island. Refusing to take pension from the Japanese government, he wrote for magazines to get by. He died at 94.

Takuma Nakahira (1938-2015)

“Has photography been able to provoke language?” Takuma Nakahira asked in March 1970, nearly eight months before his book was released. “Only through human use can a language be given life.” Tokyo-born, Nakahira was one of the most influential figures in contemporary Japanese culture. As the founder of Provoke (Purovoku), the short-lived experimental magazine that featured photographs like Daido Moriyama, Bure Boke, his extensive writings shaped standing views on Japanese literature, film and photography. His photobook, For a Language to Come (Kitarubeki kotoba no tame ni), has been described as “a masterpiece of reductionism.”

Nakahira studied Spanish at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. After graduation, he worked as an editor at the art magazine Contemporary view (Gendai no me). Two years later, he left the magazine in order to pursue his own career as a photographer. In 1990, along with Seiichi Furuya and Nobuyoshi Araki, Nakahira was presented with the Society of Photography Award.

In 1973, Nakahira burned his entire early archive, as he had become increasingly concerned that his work had become cliché. Coupled with a traumatic memory loss he later suffered, his work remains fairly obscure outside of Japan. His first U.S. solo exhibition was recently on view at Yossi Milo Gallery in New York. He died on Sept. 3 at 77.

Dennis Sabangan (1973-2015)

Dennis Sabangan, who died on July 29, was European Pressphoto Agency’s (EPA) chief photographer in the Philippines. Before joining the agency in 2003, he worked as a photographer for major Philippine newspapers and served as chairperson of the Philippine Center for Photojournalism for two years. Sabangan covered the 2004 Tsunami, the Myanmar unrest, the U.S. war against terrorism in Pakistan and Afghanistan, the World Cup and the Euro Cup soccer, as well as the 2008 Olympics, the Australian Open, typhoon Haiyan and the Pope’s visit to the Philippines. “For him, photojournalism was more than just taking a picture and making the front page of the newspaper,” says his sister, Antonia Sabangan. “It was his way of communicating something that is happening somewhere in the world.”

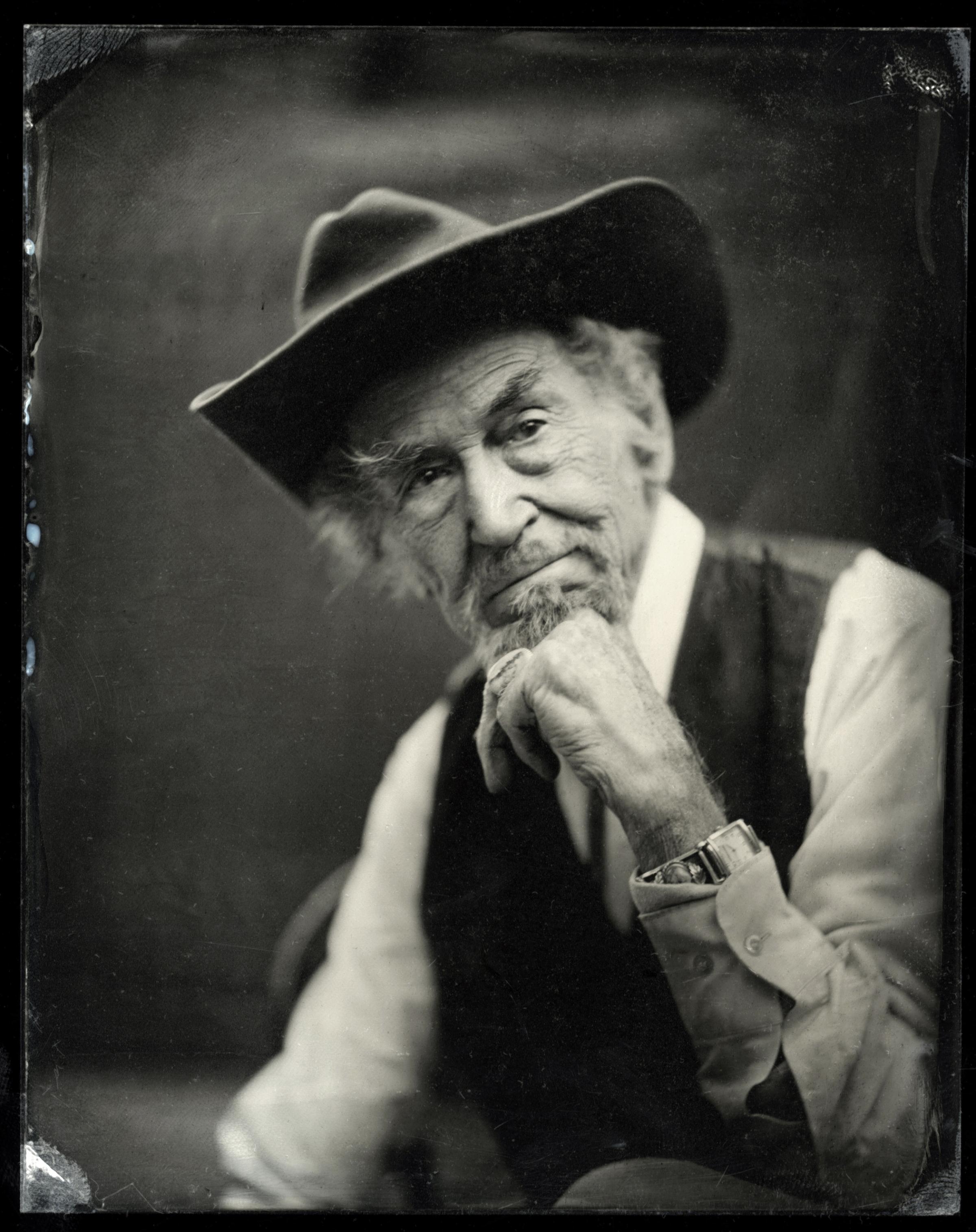

Rondal Partridge (1917-2015)

Son of renowned photographer Imogen Cunningham, Partridge began helping his mother in the darkroom at the age of five, when he became intimately familiar with the great Western photographers of his time. At 17, he apprenticed for Dorothea Lange and in 1937, he joined Ansel Adams in Yosemite, lugging heavy equipment up and down the park’s peaks. On several occasions, he was fired, including the time when he tied Adams’ shoelaces together and made him fall on his face.

Unlike Adams’ images of the natural landscapes, Partridge documented the influence of humanity’s imposition on nature and environmental changes in the San Francisco Bay area for nearly 70 years. His best-known photograph, “Pave It and Paint It Green,” shot in 1965, is a view of the Half Dome in Yosemite, clogged by row upon row of parked cars. “He was totally kinetic, always in motion,” says his daughter, Elizabeth Partridge. “I’m sure he was a trial for his mother and father to raise because we used to say that if he were a kid now, he’d be put on Ritalin or something. He was always full of ideas, and he didn’t accept the parameters that most of us kind of got organized into.” He died of natural causes on June 19 in Berkeley at 97.

Igor Fedorovich Kostin (1936-2015)

Igor Kostin, a Ukrainian photographer, was one of five photographers who captured the Chernobyl disaster in Pripyat in Ukraine. He was working for Novosti Press Agency (APN) during the disaster and flew over the nuclear power plant in a helicopter within hours of the explosion on April 26, 1986. Kostin returned repeatedly to the contaminated zone in the following months and years to document the cleanup efforts and expose the problems still existing. He, himself, was inflicted by illness related to radiation effects. He died in a car accident in Kiev at 78.

Denis Roche (1937-2015)

Editor, photographer, theorist, but mainly poet, Denis Roche, died on Sept. 2 in Paris at 77 years. For 30 years, he created and directed the collection Fiction & Cie at Editions du Seuil. He also founded, in 1980, a progressive quarterly magazine, Les Cahiers of Photographie, with Gilles Mora, Claude Nori and Bernard Plossu. In 1987, he received the Great Photography Prize of the City of Paris.

He was devoted to black-and-white photography, as he felt it was more useful for creating new forms, new shapes and abstractions. “He was a writer and a photographer,” says Mora. “This is very rare because poets like Allen Ginsberg were writers taking pictures casually. But not Denis Roche. He was working different paths and, for him, photography was as important.”

Liam Quigley (1954-2015)

Liam Quigley, described as “Ireland’s pioneering rock photographer” by Hotpress magazine in 2012, grew up in a musical family. He was given his first camera at just 12 years of age, and when he turned 16 he was on tour with Thin Lizzy. Quigley was a force in the music scene, photographing rock legends like Kenny Loggins, Bob Dylan, Jonny Cash, McJagger, Abba and U2 in his characteristic black-and-white style. He shot for Rolling Stone and Spotlight, Ireland’s national music magazine. His photographs are plastered in pubs from Dublin to Berlin and New York. As a character, he was mischievous. “He would go anywhere for that one good shot,” says his brother, Gerry Quigley. “He’d climb up on something or move to the side of the stage or even climb a tree if it meant getting that photo nobody else could get. He once ran out to the runway at the airport to capture Abba when they first got out of the plane.” Quigley died Oct. 22.

Adam Ward (1988-2015)

On Aug. 26, 27-year-old Adam Ward and his coworker, news reporter Alison Parker, were killed during an on-air shooting by a man who authorities say was a disgruntled ex-employee of WDBJ, the Virginia-based news station where they worked. Ward, 27, had grown up in Salem, Va. He had worked at WDBJ since July, as a videographer and an occasional sports reporter. He was described by his colleagues as fun loving and reliable. At the time of his death, Ward was engaged to WDBJ producer Melissa Ott, who had plans to leave with him for a journalism job in Charlotte, N.C. that month.

“He brought that joie de vivre to everything that he did,” says WDBJ general manager Jeffrey Marks. “If I walked in the backdoor of the building and the first person I saw was Adam, I knew it would be a good day. He gave out a boisterous ‘Hey Jeff, how are you doing?’”

Leroy Woodson Jr. (1944-2015)

The son of an American diplomat in France, Leroy Woodson Jr. was educated at the Ecole Pascal in Paris. When he was back in the U.S. he studied journalism and photography. He worked with Gamma, as well as publications such as National Geographic, Washington Post, Newsweek, LIFE, Forbes, Fortune and Business Week.

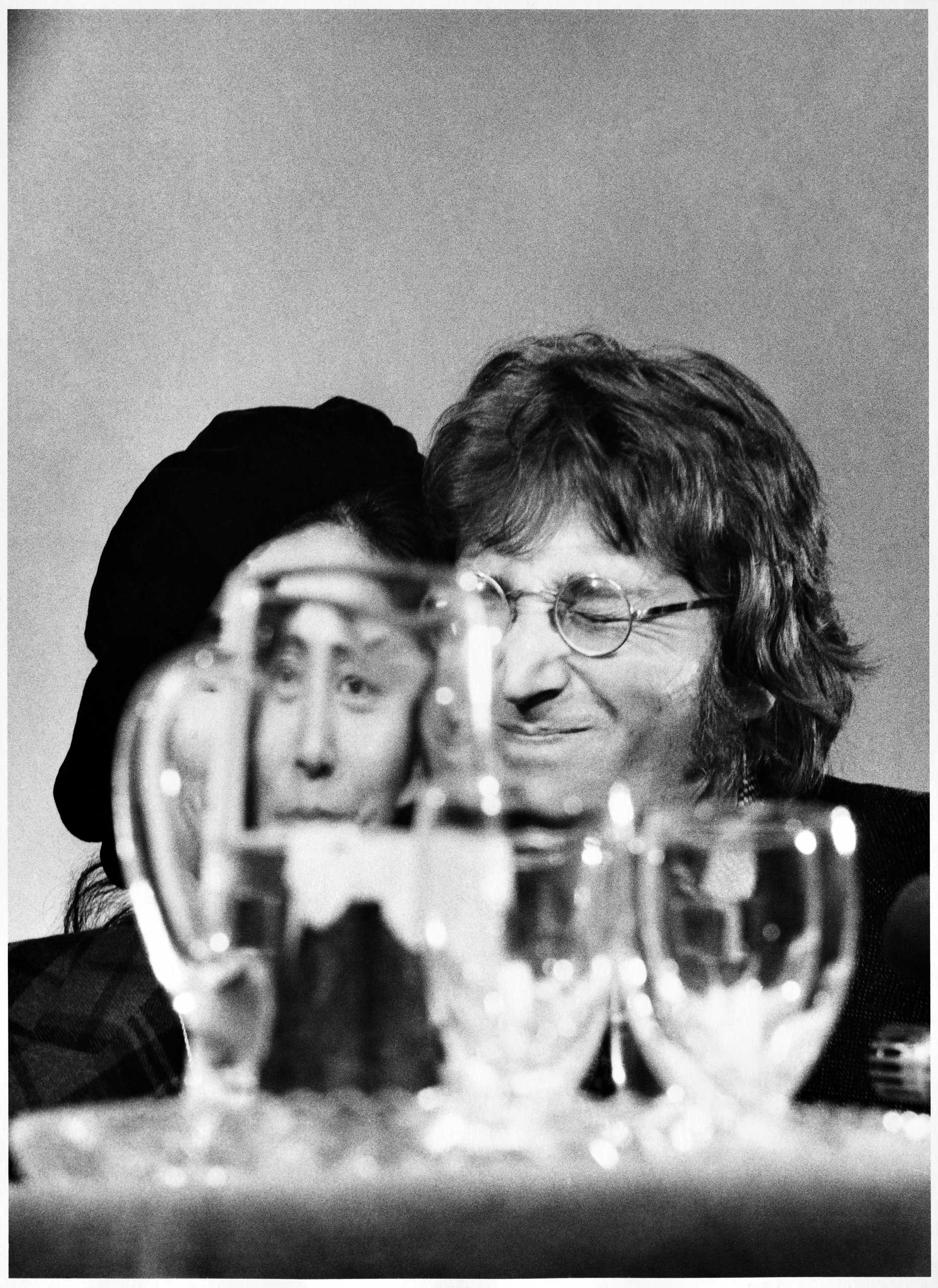

He captured lobster fishermen in Maine and Argungu fishing festival in Nigeria, as well as road restaurants in the U.S. He photographed Susan Sarandon and Woody Allen, as well as Eddie Murphy and Andre Courreges. His most iconic photograph was that of Yoko Ono and John Lennon in 1971 while at a press conference of an art exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse. The 70-year-old photographer died Feb. 12. “He was always a great companion at a dinner party,” says his daughter, Isabella Moses. “He was never without a story to tell from his days traveling the world as a photographer and as a writer. He was always well read and well informed about the day’s news… so good luck winning a debate.”

Kiripi Katembo (1979-2015)

Known as the “Master of Reflection,” Congolese photographer, painter and film producer Kiripi Katembo died on Aug. 5 at the age of 36 in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Born in Goma, Katembo studied at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Kinshasa. His work documents the daily life of the inhabitants of Kinshasa and his country’s unstable political conditions. “Photography also provides a way of seeing beyond reflection,” he once explained in describing his best-known series, Un Regard. “I want each image to tell of the children born here who have to grow up surrounded by pools of water, and of the families who survive while others leave to live in exile.”

Remembering Lars Tunbjörk: Legendary Color Photographer of the Absurd

Lars Tunbjörk (1956-2015)

Born in Boras, Sweden, Lars Tunbjörk’s signature ultra-vibrant color style emerged after he studied American photographers of the 1970s like William Eggleston and Stephen Shore. His 1993 series Landet Utom Sig depicted contemporary European life on holiday. Publishing more than 10 photobooks, Tunbjörk, 59 when he died, explored everything from depression to modern life.

“Tunbjork’s images amplified the most mundane and absurd aspects of modern life in a surreal way, using the hard light of flash photography, which became his signature style and influenced a generation of photographers after him,” wrote TIME Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise Paul Moakley. “He never used light for mere effect but crafted it like a master painter to accentuate color and amplify the humdrum details of the everyday. Whatever subject he was documenting, suburbia or offices spaces, he did it in such a revealing way with a stark, clear-eyed honesty layered with an sense of dark humor.”

Ray Demoulin (1930-2015)

A former director of Kodak, Ray Demoulin was also a mentor to photojournalists, publishers, curators and gallery owners alike. He died on March 3. “Ray was one of a kind,” says his friend, Eliane Laffont. “Gentle, passionate, kind and generous, committed to helping us grow and make our projects come to life, with sometimes crazy ideas but always to improve the world of photography.”

David Laidler (1967-2015)

David Laidler died peacefully in his Brooklyn home on August 11th at 48 after a long illness. Having worked in the industry for over 25 years, he was known for his ability to mentor new talent. He was the first director of Reportage by Getty Images and he founded the Getty Images Grants for Editorial Photography. “He was a real champion and mentor to all of the photographers he represented and they all became his lifelong friends,” says his friend and colleague Aidan Sullivan. “During his time at Getty Images David was instrumental in the founding of our Editorial Grants and we felt it would be a fitting tribute to name one of them in his honor so from 2016 we will have The David Laidler Memorial Award in his memory.”

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @rachelllowry.

Mia Tramz, who edited this photo essay, is a Senior Multimedia Editor at TIME.com. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @miatramz.

Correction: The original version of this article misstated the date of Dan Farrell’s death. It was April 13. It also incorrectly described his experiences with celebrities and misidentified the daughter who spoke to TIME. Farrell golfed with Bing Crosby and rode the subway with Bob Hope. The daughter is Kathy Farrell Natoli.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com