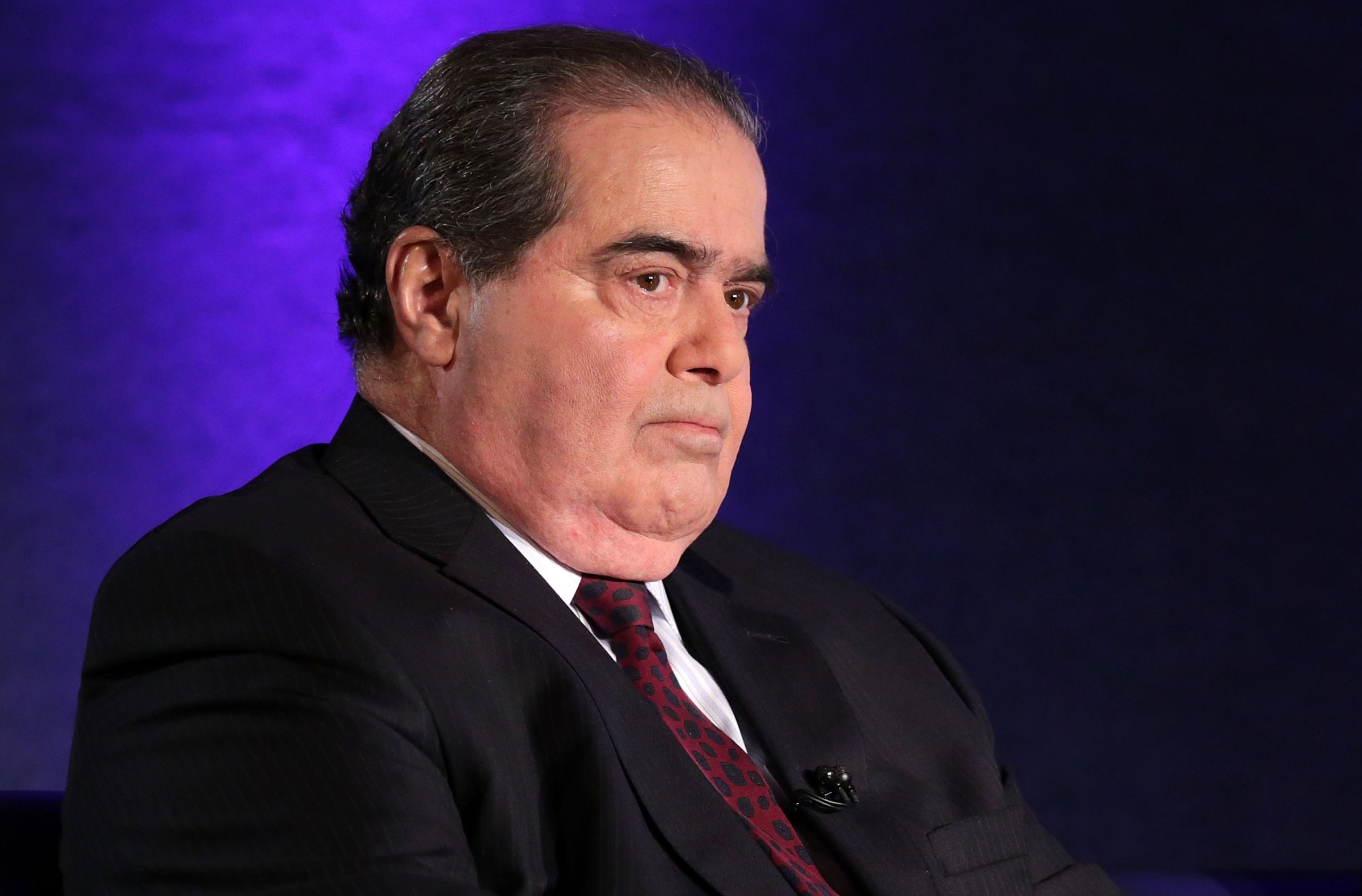

I wish I didn’t have to respond to Justice Antonin Scalia’s recent remarks during oral arguments in Fisher v. University of Texas, a case over whether the factor of race in 20% of the university’s admissions decisions is constitutional. But I have to. His are the latest in what seems like an all-out assault on black people in this country, where we live, where we pray and now where we go to school. I don’t know what’s fueling the fire—whether it’s the actions of police officers or the bile of Donald Trump and those who support him—but it feels like some white people are coming unhinged.

Justice Scalia said: “There are those who contend that it does not benefit African Americans to get them into the University of Texas where they do not do well, as opposed to having them go to a less-advanced school, a less—a slower-track school where they do well.” He went on to say: “I’m just not impressed by the fact that the University of Texas may have fewer. Maybe it ought to have fewer. And maybe some—you know, when you take more, the number of blacks, admitted to lesser schools, turns out to be less.”

In effect, he is saying excellent schools aren’t the best places for some black students. The excellent schools do more harm than good.

Now there is little in Justice Scalia’s jurisprudence that would lead me to believe that he genuinely cares about what’s best for black students or is even mildly committed to the value of diversity. So I am not interested in responding to the substance of his claim. I will leave that to others.

What does interest me is what motivates his comments. This entire case reflects the hysteria around the perceived belief that meritless black people are stealing opportunities from well-deserving whites. Yet to believe that is to ignore the facts. Abigail Fisher, the plaintiff, thinks that bad black students took her place at the University of Texas. But 42 white students with lower test scores and grades were also offered provisional admission. Why not single them out? To challenge only the five black and Latino students with lower scores and grades suggests that, for Fisher and her lawyers, the problem is not merely the process, but certain people who benefit from it and should not.

At the heart of all of this is the unseemly and ever-persistent belief that white students matter more. Others are unworthy. This is the nature of the value gap: that no matter our stated principles or how much progress we think we’ve made in changing society to reflect them, white people are valued more in this country than others. That belief undergirds racial inequality and informs the remarks of Justice Scalia.

I hope the University of Texas prevails in this case. But my concern cuts much deeper than a defense of affirmative action. Our racial habits reflect how we see ourselves, and they are formed from what we see in the world. I think about all of those black and brown students who are working their behinds off right now in school. They face a barrage of challenges and they still excel. Excellence, they have been told, is their best armor against the value gap. And now they read the words of Justice Scalia, a white man who sits on the highest court in the land.

This is why I have to respond. I cannot let his words do harm to our babies — especially given that so much of this world conspires against them. We have to work so hard every day to keep the ugliness around us from seeping into our children’s souls, darkening their eyes, and shattering their dreams. We have to work hard to keep them from believing what people like Justice Scalia say about them. As James Baldwin put it in his essay, “The Uses of the Blues”:

In every generation, ever since Negroes have been here, every Negro mother and father has had to face that child and try to create in that child some way of surviving this particular world, some way to make the child who will be despised not despise himself. I don’t know what ‘the Negro Problem’ means to white people, but this is what it means to Negroes.

Baldwin understood the deadly implication of the value gap. And here we are facing, yet again, a challenge to affirmative action and confronting the violence of Justice Scalia’s words. I know what I am going to say to my son, who attends Brown University. “To hell with Justice Scalia; his world is dying. Keep fighting. Get your work done. And dream big dreams, son.”

Eddie S. Glaude, Jr., is the author of the forthcoming book, Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul. He is the William S. Tod Professor of Religion and African American Studies and chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com