This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Hillary Clinton says “the party of Lincoln has become the party of Trump.” Mike Huckabee recommends that Christian conservatives disobey the Supreme Court’s ruling on marriage equality just as Lincoln resisted the Dred Scott decision. Rand Paul resurrects long-discredited Lincoln dialogue to warn of imagined threats “from within” and to promise to fall to his knees to seek divine guidance.

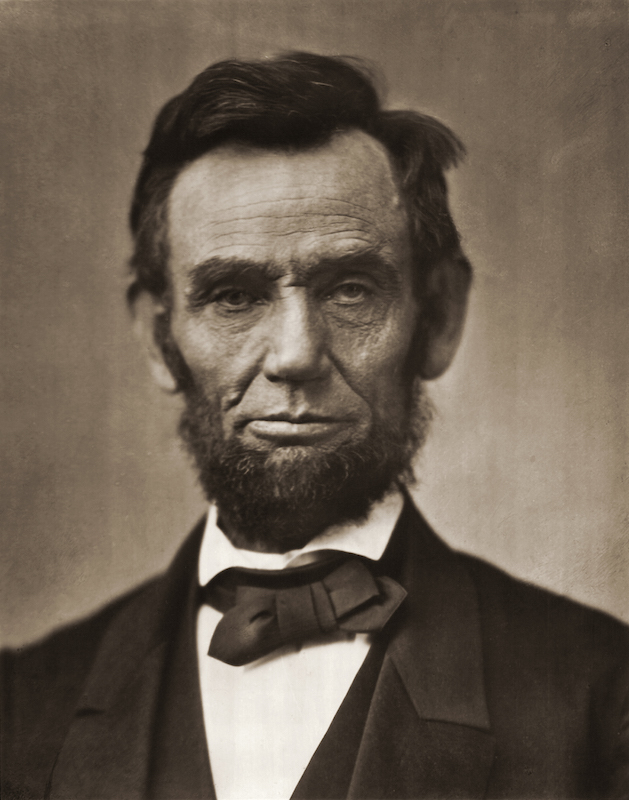

It seems that everywhere one turns during this otherwise high-tech 21st century presidential campaign, the conversation reverts to the 19th century and to the leader who still represents the ideal for both Democrats and Republicans: Abraham Lincoln. As has been the case for a century-and-a-half, politicians of all stripes continue to try “getting right with Lincoln.” But what would Lincoln himself say about the current candidates and their policy proposals, especially on the crucial issues of jobs, budgets, and economics? Though ignored by most historians (and politicians) since Gabor Boritt’s magisterial 1978 Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream (published when Jimmy Carter was president), the answers can still be easily found—in Lincoln’s own speeches and writings.

The key is to look beyond the obvious. Modern Americans focus so intently on Lincoln’s contribution to our nation’s beliefs about slavery and freedom that his role in shaping our uniquely American vision of a just and generous economic society has been largely neglected. In fact, Lincoln was unwavering in his commitment to preserve the American dream of economic opportunity for future generations, a dream he lived out himself by escaping the poverty of his childhood, and which he advocated for others throughout his political life. It was this commitment that lay behind his determination to ensure that a government dedicated to providing economic opportunity for its citizens “shall not perish from the earth.” By this logic, Lincoln largely fought the Civil War over this principle, establishing a role for government in securing and guaranteeing economic opportunity for its citizens, a covenant that has remained at the center of political debate and discord ever since, seldom so acrimoniously as today.

After all, Lincoln was the first president to use the federal government as an agent to support Americans in their effort to achieve and sustain a middle class life. Even as the Civil War commenced, Lincoln supported a program of direct government action to support his vision of America’s middle class society. Land Grant colleges received government support, the transcontinental railroad was approved, and federal income taxes were imposed to support the war—all in the name of, as Lincoln put it, clearing the paths of laudable pursuit for all, and giving all an equal chance in the race of life. Even in the crisis of war, Lincoln pursued an unambiguous pledge to middle class advancement—which ultimately did include giving African Americans the opportunity to eat the bread earned with their own hands—one of the first metaphors Lincoln ever used to advocate the free labor that would come with emancipation. No wonder Ralph Waldo Emerson mourned Lincoln’s death by remembering: “This middle-class country had got a middle-class president, at last.”

Nearly four score years later, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal became, at its core, a modern and muscular version of Lincoln’s commitment to government action to support a prosperous middle class society. In fact, FDR self-consciously defined his progressive policies in Lincoln’s language. In a fireside chat on September 30, 1934, Roosevelt said: “I believe with Abraham Lincoln, that ‘The legitimate object of Government is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done but cannot do at all or cannot do so well for themselves in their separate and individual capacities.’ ” Roosevelt found in Lincoln’s commitment to government “for the people” not only the inspiration, but the basis, for positive government action to rescue the economy amidst the worst crisis since the time of Lincoln.

FDR’s commitment to the well-being of all citizens was manifested by his New Deal government stimulus programs to provide jobs for all able-bodied workers. Roosevelt treated the government as a direct employer not only of last resort but of first resort. To put people back to work, he created, among other initiatives, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Civil Works Administration, the Public Works Administration, and later the Works Progress Administration.

Both Roosevelt and Lincoln understood that the future of American democracy depends above all on a thriving middle class—a belief, and a future, we risk losing today, when the middle class is faced with so little government support.

The dominant Republican-conservative ethos under Presidents Ronald Regan and George W. Bush reversed the policies advocated by Lincoln and Roosevelt to use the government to build and sustain an American middle-class society. The continuing efforts by conservative politicians to reduce taxes on the wealthiest Americans have resulted in a government with few resources to support efforts to maintain a middle-class society—not even to resurrect the crumbling infrastructure on which rich and poor alike depend. Lincoln was among the pioneers who believed that economic development—what he called “internal improvements”—modernized connections between regions and people, and put Americans to work in the process.

Above all, Lincoln and Roosevelt understood that America must operate on the moral principle of fairness. Americans must view their government as pursuing policies that are fair to all citizens, and not hopelessly skewed to those who, by dint of their wealth, can command greatest control over government policy and the distribution of society’s resources.

Fulfilling Lincoln and Roosevelt’s vision of a successful middle class society is a continuing work in progress, a debate well worth pursuing. The nation’s political and economic future will increasingly depend on the ability of contemporary political figures to sustain positive public sentiment to support positive government action “for the people.”

If they are really pledged to serve the common good, modern politicians can restore the positive path of American history by embracing the Lincoln-Roosevelt tradition of using government effectively to address the challenges our society faces, not blaming the government for the problems their indifference has created. Only then will our leaders again “get right with Lincoln”—and his vision for the country. Only then can the country complete the “unfinished work” that Lincoln talked about at Gettysburg 152 years ago last month—and provide a true government of, by, and for the people.

Harold Holzer, a prize-winning historian, and Norton Garfinkle, a respected historian-economist, are the authors of the just published book, A Just and Generous Nation: Abraham Lincoln and the Fight for American Opportunity.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com