By the standards of the modern presidency, President Obama was roughing it during his appearance on the the reality show Running Wild With Bear Grylls, airing Thursday. In an effort to spotlight the effects of climate change on the nation’s northern wilderness, Obama allowed the survivalist TV star to do decidedly un-presidential things like feed him a bear’s leftovers.

Harrowing stuff, but not exactly a death-defying, stranded-in-the-wild situation. At least one other U.S. president, however, knew how the real thing feels. Completely unsurprisingly, that president was Teddy Roosevelt, the early 20th-century leader famous for his devotion to the great outdoors and ideals of rugged masculinity.

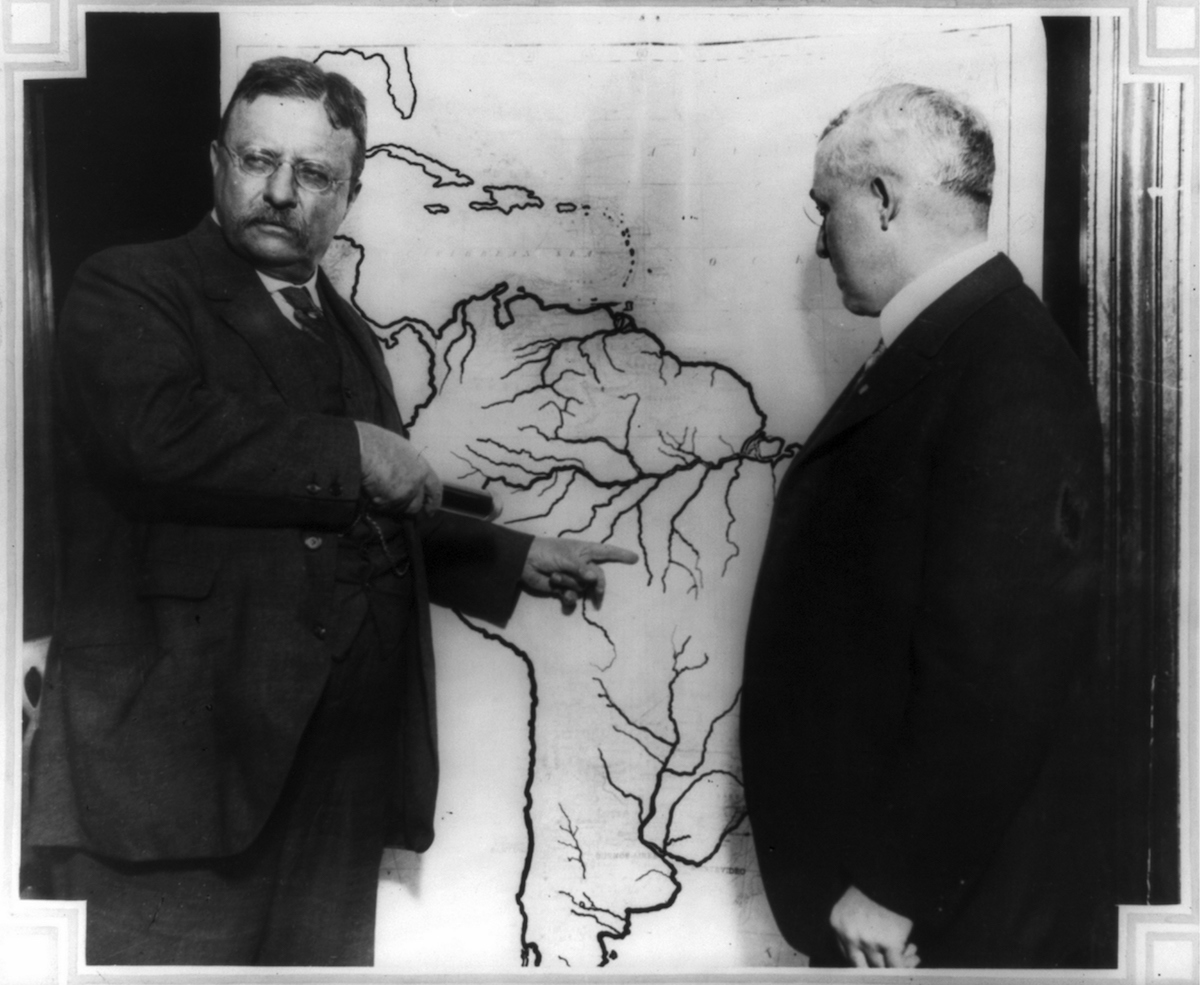

Roosevelt’s most perilous expedition came when he was invited to speak in Brazil in 1913, as he was struggling to recover his reputation after losing the 1912 election. Once he arrived, the Brazilian Foreign Minister offered Roosevelt and his son Kermit places on an expedition exploring the appropriately named River of Doubt, a piranha-filled waterway that ran through malarial climates.

Along the way, Roosevelt was nearly bitten by a venomous snake, members of his party were attacked by the area’s indigenous peoples and Kermit faced his own mortality, as author Candice Millard later explained for TIME:

Kermit’s paddler had drowned in one of the many deadly rapids that studded the river. Kermit, 24, had nearly died in the same accident, and Roosevelt lived in constant fear that he would lose not his own life on this expedition but his son’s. Time and again, the men also lost canoes and precious provisions to the rapids. Game and fish eluded them, and they were reduced to searching, often in vain, for Brazil nuts, hearts of palm and the sweet, white sap of milk trees. One of the porters, roundly despised for his laziness and violent temper, had begun to steal food. Out of desperation and rage, he eventually murdered another man on the expedition.

By the time the expedition reached what appeared to be an impassable set of rapids–a series of six waterfalls, the last of which was more than 30 ft. high—Roosevelt was gravely ill, and his men were beaten down by exhaustion, hunger and fear. The only man among them who believed that they could get their dugouts through the rapids was Kermit. Having spent much of the past year building bridges, he was extremely skilled with ropes, a talent that had already saved the expedition countless times as it encountered series after series of rapids.

Though Kermit’s expertise would help most of the explorers make it home safe, Roosevelt was weakened by the tropical illness and infections he contracted on the journey. He died suddenly only a few years later, with doctors at the time positing that his illness in Brazil was a contributing factor. But, as TIME reported in 1935, the expedition was in many ways a success. Roosevelt’s account of the terrain proved to be accurate, putting an end to a joke that the river’s name referred to the question of whether it really existed. And the Brazilian government decided to rename the river after Roosevelt. It is now known as Rio Roosevelt or Rio Teodoro.

When the Roosevelt Memorial Hall at the American Museum of Natural History opened in 1936, it included a “a towering mural painted by William Andrew Mackay” in which “a comely female figure in Grecian dress, representing the river, is pouring a torrent from a vase. In the background is a map with the river labeled ‘Rio Téo-doro.’ Below, kneeling at a portable table, Kermit Roosevelt keeps a record of the expedition. In the centre two expeditionists are pushing aside jungle growth so that a burly, square-headed figure in khaki breeches and boots may gaze with hat in hand upon his river.”

The mural was restored in 2012.

Read more from 1935, here in the TIME Vault: Rio Teodoro

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com