How do you feel about old people? Your answer appears to be connected with how well your brain holds up against Alzheimer’s disease, according to a series of two new studies published in the journal Psychology and Aging.

The researchers, from the Yale School of Public Health, say it’s the first time this type of risk factor has been linked in a study to the development of brain changes linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

In the first study, researchers looked at data from 158 healthy people without dementia enrolled in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). In order to find out how people in the study felt about age stereotypes, researchers used a scale with statements like “older people are absent-minded” or “older people have trouble learning new things.” People in the study gave these answers when they were in their 40s.

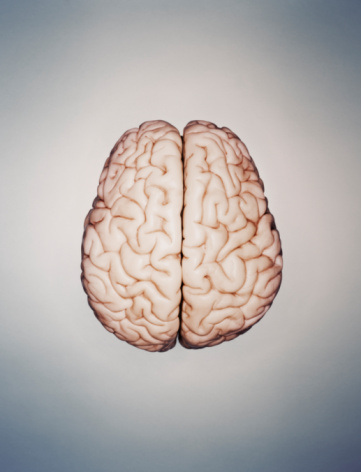

About 25 years later, when people in that same group were about 68 years old, they began about a decade of annual MRI brain scans to determine the volume of their hippocampus. Loss of volume in that brain region is associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

People who held more negative thoughts about aging earlier in life had greater loss of hippocampus volume when they aged. In other words, the researchers say, people who held negative age stereotypes had the same amount of decline in three years as the more positive group had in nine years.

In the second study, researchers examined two more markers of Alzheimer’s disease: the buildup in the brain of amyloid plaques—clusters of proteins that accumulate between brain cells—and neurofibrillary tangles, twisted strands of protein that build up in brain cells. To do so, they used brain autopsies of people who also had had their attitudes about aging measured.

The results were consistent: People who held more negative age stereotypes had significantly higher scores of plaques and tangles than people with more positive feelings about growing old.

The researchers didn’t look at a mechanism by which negative stereotypes might exert an influence on the brain, but they suspect that stress is the driver. Animal research shows that exposure to chronic stress can lead to the same biomarkers examined in the new study, says Becca Levy, lead author of the study and associate professor of epidemiology and psychology at the Yale School of Public Health.

Past laboratory research on humans shows that when people are primed with negative age stereotypes and exposed to stressors, they have a greater cardiovascular response, which is linked to heart events. And research from 2012 conducted by Levy and others found that people who had more negative age stereotypes before they had reached old age had significantly worse memory performance later in life.

It may be unsettling to think that negative cultural stereotypes about age could be having such a profound effect on how our brains age. “We know from other studies that as young as age four, children taken in stereotypes of their culture,” says Levy. But the results can be interpreted a different way, too. “Positive age stereotypes seem protective of not experiencing these biomarkers,” she says—so if we can find a way to promote positive age stereotypes on a societal level, our brains may be better off once we reach old age.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Mandy Oaklander at mandy.oaklander@time.com