In the early 1950s, a young teen boy used to bring hit records into a bar on New York City’s Upper East Side. In exchange for keeping their jukebox current, the bartenders would let the teen have a drink on the sly. One afternoon he heard a record there that he didn’t provide, and it would go on to change his life

“I remember it vividly as a Tuesday,” says the now-77-year-old Jonathan Schwartz. “I gave the bartender a dollar bill and asked him for ten dimes. So I listened to this record, which was called ‘The Birth of the Blues,’ ten times. The singing of it was so virile, so masculine, so understandable, so intense, so beautiful. I’d never heard anything like it.”

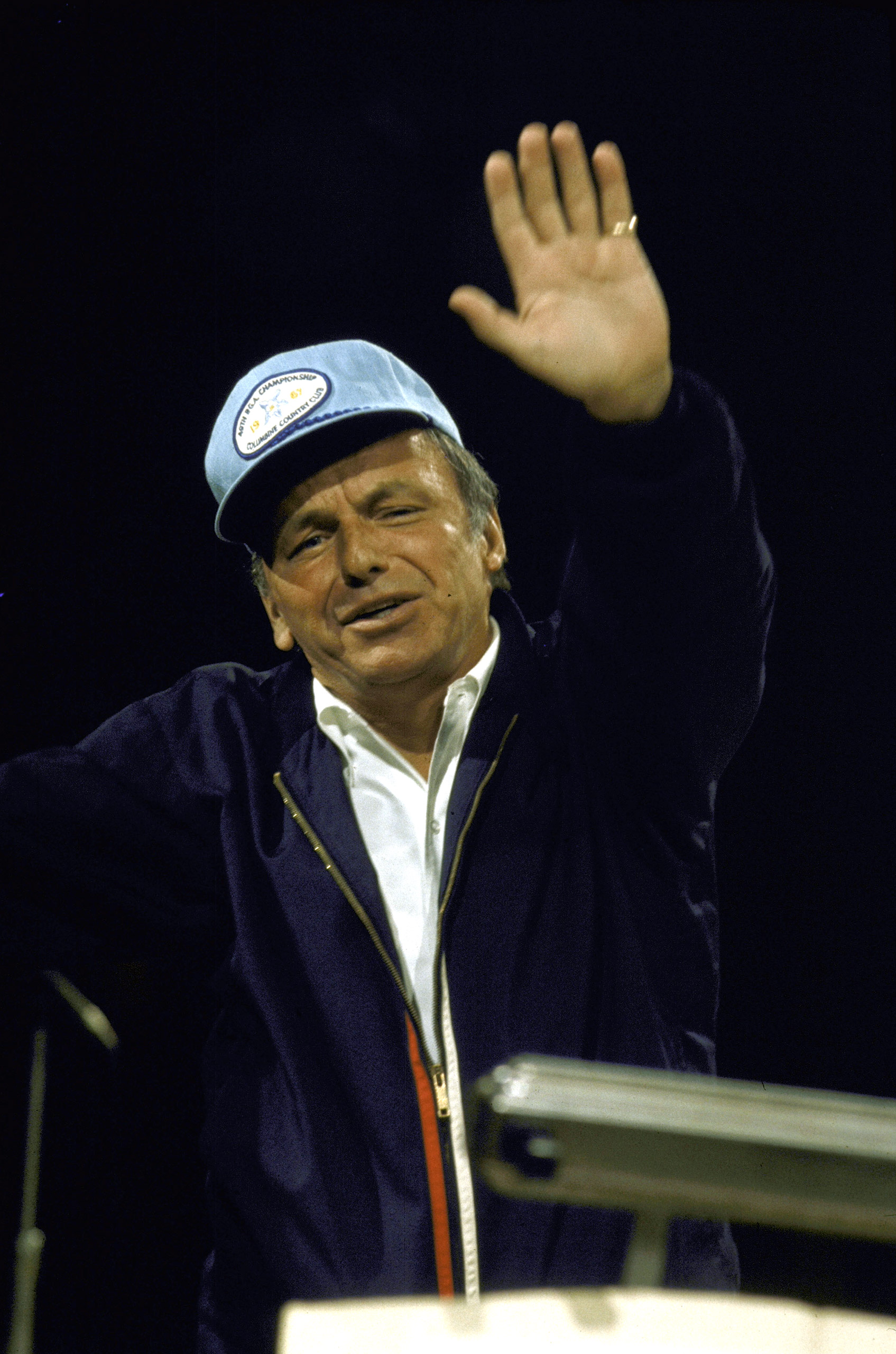

Today, Schwartz is a radio personality responsible for sharing several hours’ worth of Frank Sinatra each week: between his weekend show on WNYC, New York City’s flagship public radio station, and his 24-7 online station, The Jonathan Channel, he spins Sinatra every single day. Schwartz says that’s because even now, 100 years after the singer was born, on Dec. 12, 1915, the public appetite for the crooner is still going strong.

What is it about Sinatra that has made the music endure so well? One of Sinatra’s special abilities, Schwartz says, was finding what the arranger Nelson Riddle called “the tempo of the heartbeat.”

But Sinatra’s great timing wasn’t limited to music. Much of his sound–and therefore his success–owes to his is being born in 1915 and finding his voice in the 1940s and ‘50s.

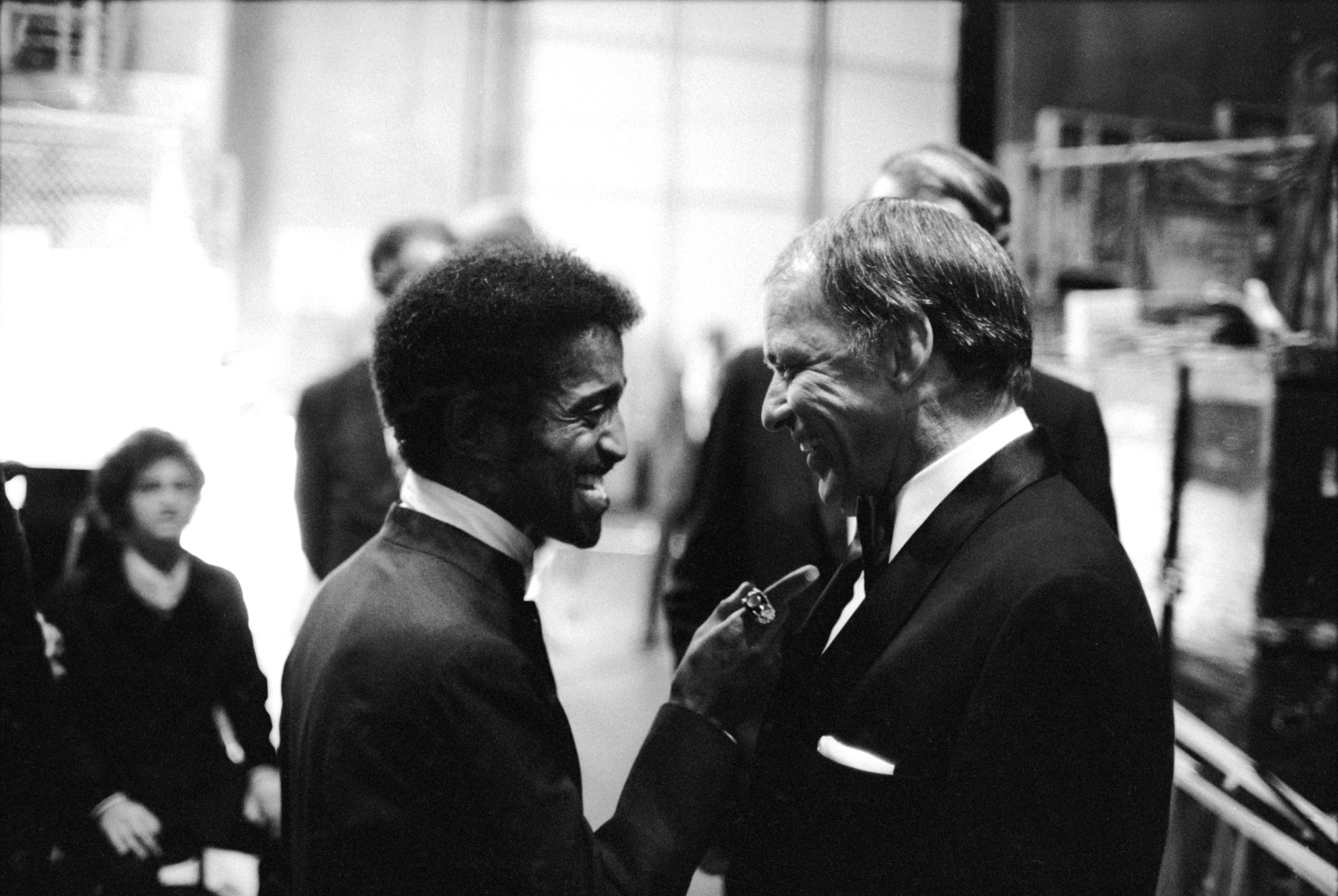

“Sinatra grew up in the world of Bing Crosby,” Schwartz says, and Crosby’s style dominated the airwaves well into the 1940s: the ideal male singer was a crooner, someone Schwartz summarizes as a “nice” singer. Sinatra would later say that, while he idolized Crosby, he knew that he didn’t want to sing like that—even before he knew what singing some other way would sound like. The eventual result, for Sinatra, was an emphasis on conveying emotion. And, because he was doing something different, and doing it extremely well, he would come to represent that new style of music.

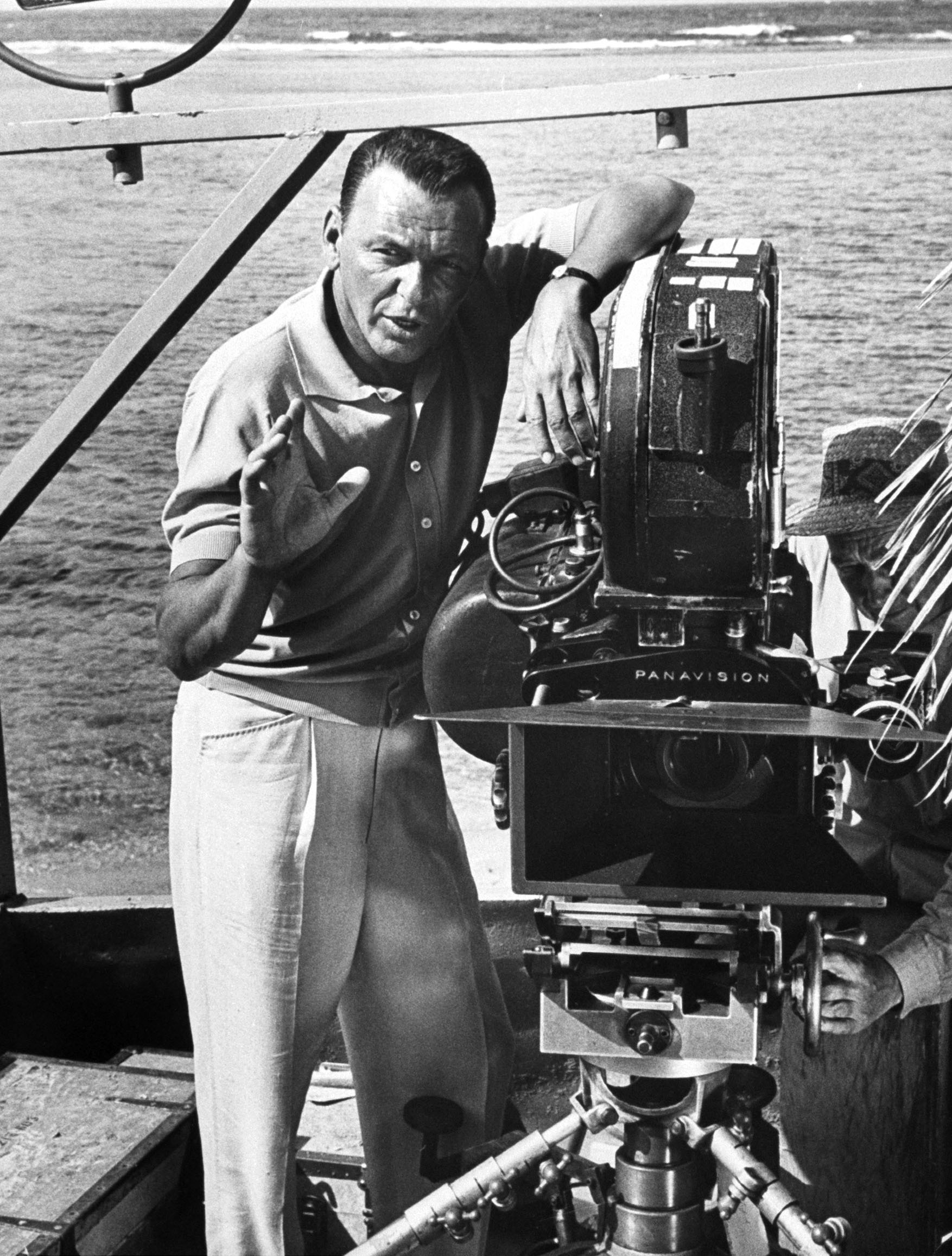

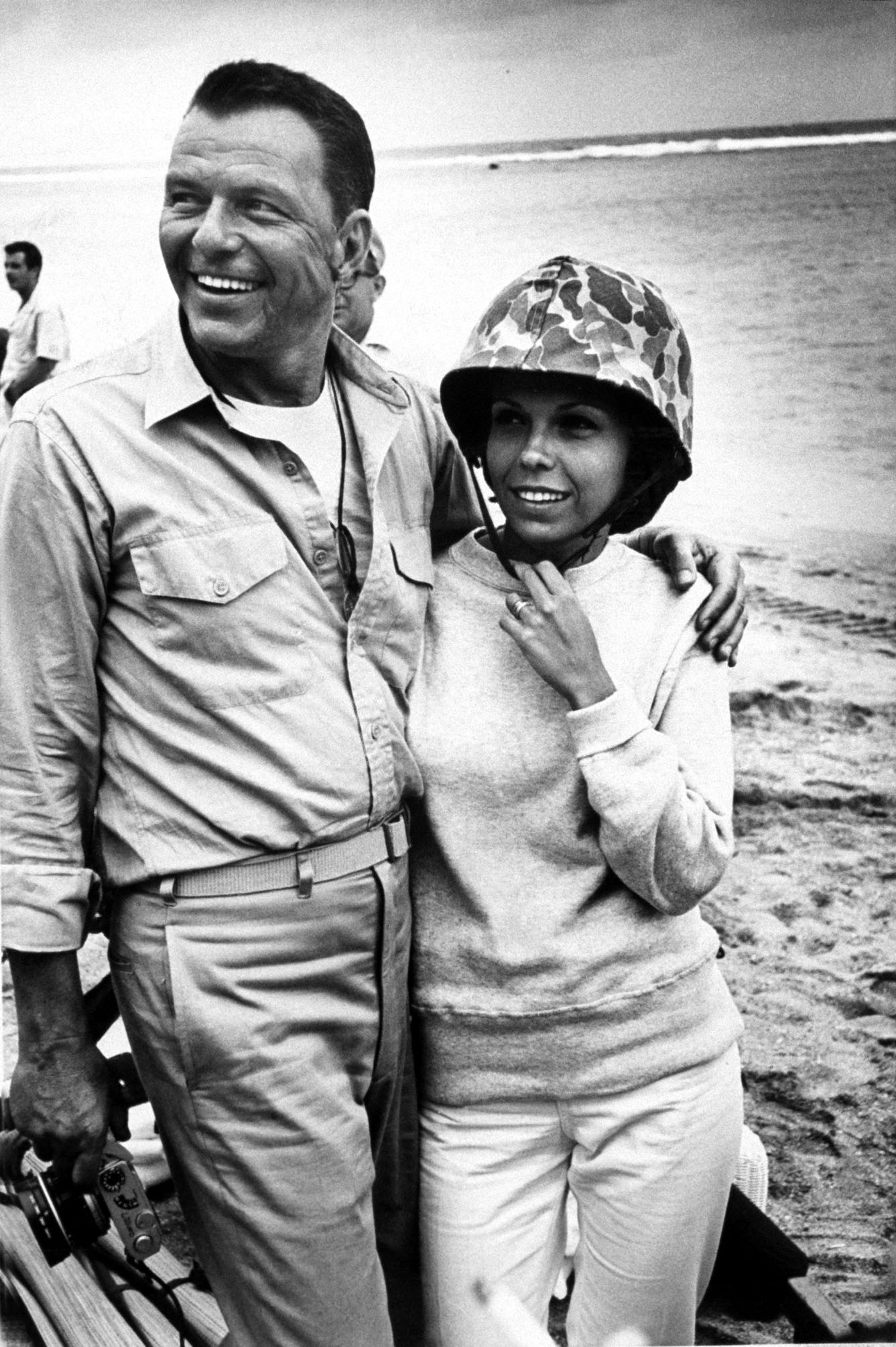

“Without any question, he was the greatest interpretative singer who ever lived, in any music,” Schwartz says. Though singers who don’t write their own songs sometimes get less credit these days, Schwartz believes the interpretative part of a singer’s art—the ability to communicate the feeling in something written by another person—is just as important, and Sinatra’s ability to do that has meant that his music appeals emotionally to a range of audiences. “I don’t think he was in command of other parts of his life,” Schwartz says, referring to Sinatra’s tumultuous personal life, “but he was in command of his feelings and his entire being when he was singing.”

Differentiating himself from the singers of the 1940s wasn’t the only way that Sinatra capitalized on changing times.

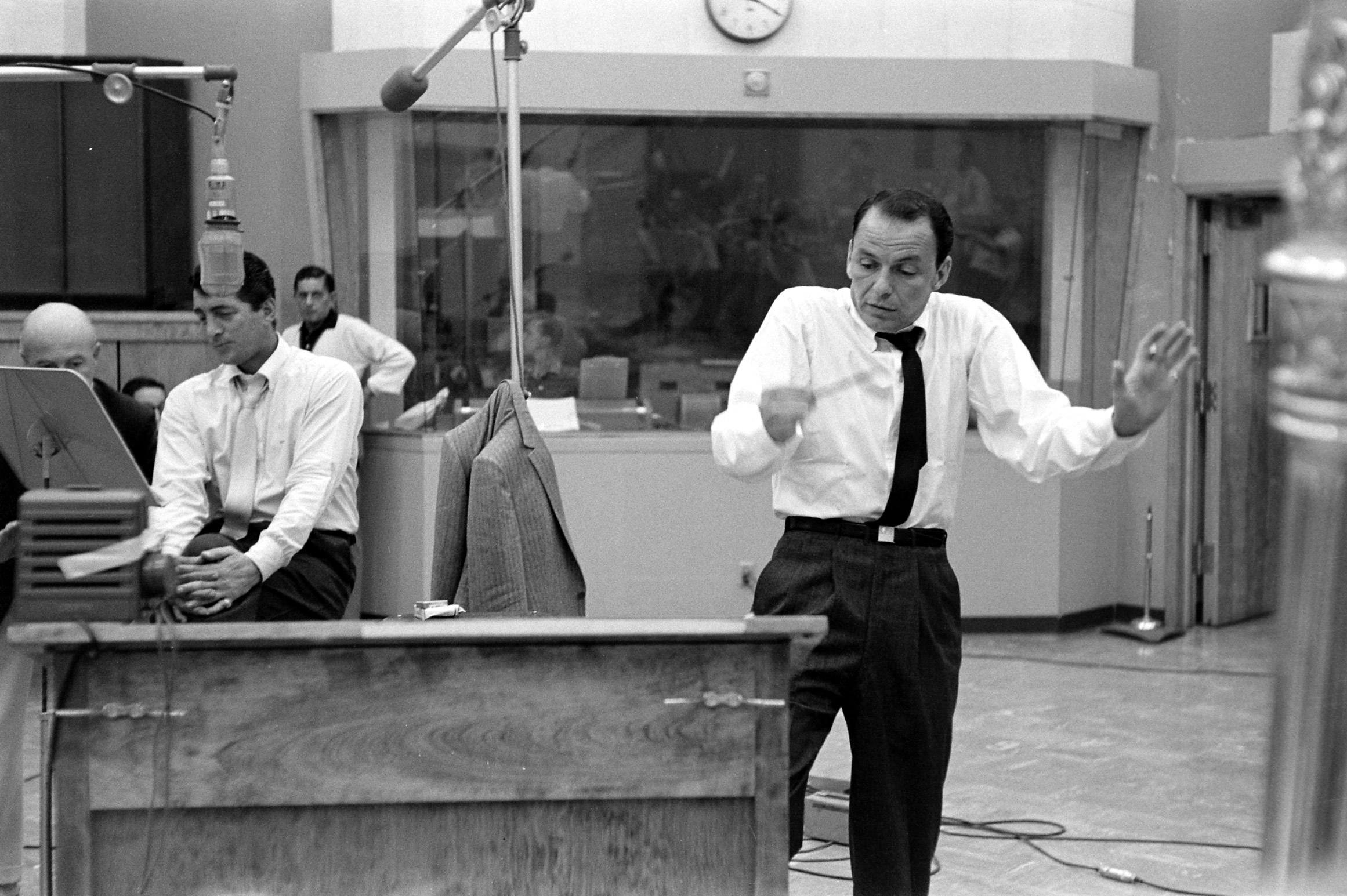

In the 1940s, the recording industry was structured around people Schwartz compares to short-story writers, who released 78-rpm records with one song on each side. And, for about a decade of his career, that was what Sinatra did too. Long-playing 33 1/3-rpm records did exist, but they hadn’t made inroads into a market where most consumers only owned the equipment to play 78s. By the mid-1950s, that had changed, and 33 1/3 records were everywhere. That changing technology allowed Frank Sinatra to take his interpretative singing to the next level, as he controlled not just the delivery of a song but also the full arc of an LP.

“He sequenced the songs so that it played like a novel, not just a bunch of short stories,” Schwartz says. “It’s not only Sinatra [the singer] but his taste in songs — every album that Sinatra made is a Sinatra album, right down to the covers.”

And at least according to Schwartz, it also helped that the music of the 1940s and ‘50s was just plain good—“It was the music of the streets, only it was beautiful,” he says.

But these elements alone don’t fully explain the Sinatra phenomenon. Asked why he thinks it’s likely that nobody will ever be as good as Frank Sinatra was, Schwartz pauses.

“Why,” he asks, “was there one Babe Ruth?”

Read TIME’s full commemorative Frank Sinatra issue from 1998, here in the TIME Vault

Best of Frank Sinatra

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com